Review by Ian Keogh

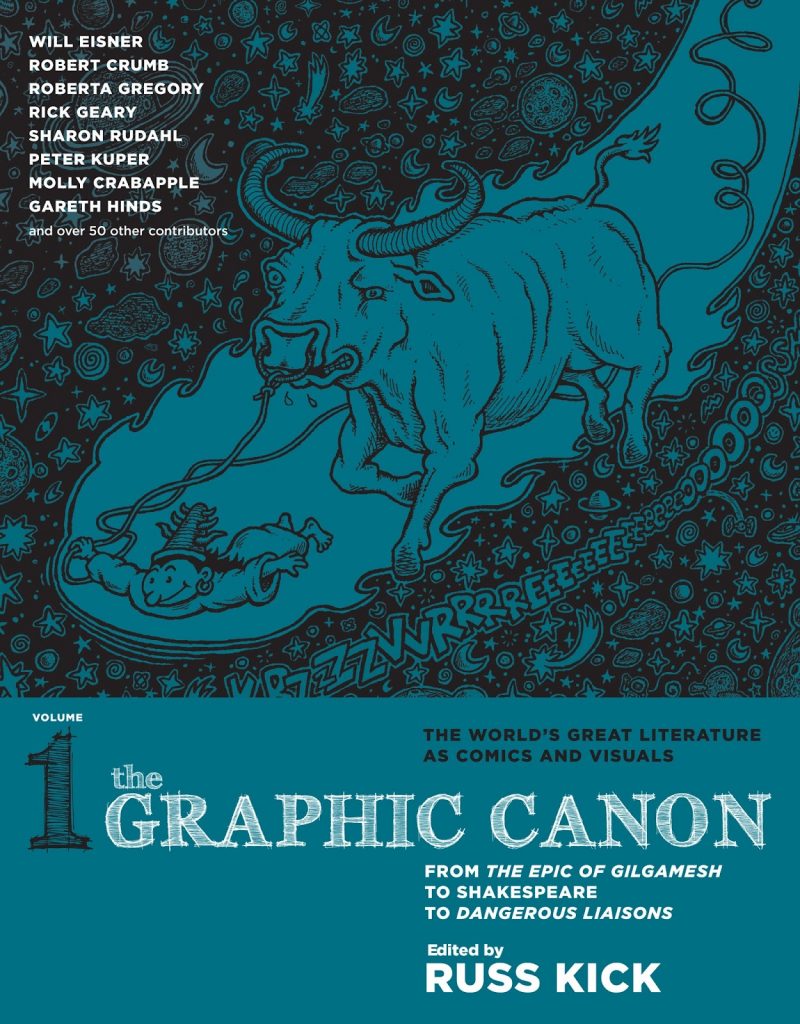

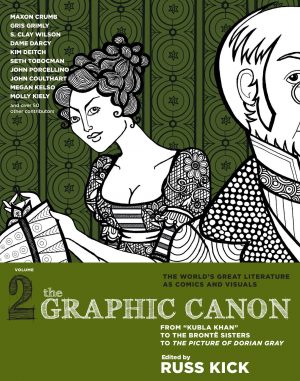

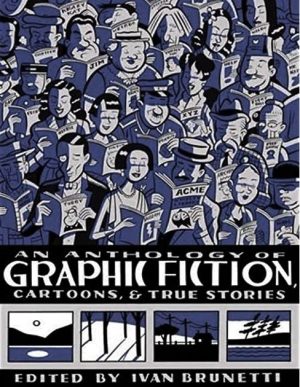

The Graphic Canon is a fascinating concept, not only having comic creators adapt myths, legend and literature that’s stood the test of time, but arranging it in chronological order over three volumes. It begins with the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh, and finishes with David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, although this volume’s breaking point is the 1792 novel Dangerous Liaisons.

Even before examining the comics, the dedication of editor Russ Kick should be noted. He not only co-ordinated the Graphic Canon, but provides a short essay on each work, contextualising the literary and historical importance of every adapted piece and explaining the approach of the creators, each of whom is also allocated a biography running to a minimum of five lines. Whether or not there’s agreement with his choices of creator or work, his is a generally unsung job very diligently carried out.

Even at 500 pages per volume The Graphic Canon can only be a primer. In some cases, such as Seymour Chwast’s Divine Comedy, Ian Pollock’s King Lear and Will Eisner’s Don Quixote, longer works exist. Other creators have just dipped their toes in the water to adapt excerpts. Also apparent is that Kick has approached many artists better known for illustration or design than comics, and their adaptations reflect that perspective while offering the broader premise the title suggests. Some supply abstracted pictures accompanied by blocks of text. A few don’t even bother with the text, producing illustrations inspired by the original work, yet Sanya Glisic’s nightmares inspired by The Tibetan Book of the Dead are a powerful statement with no knowledge of the source. Kick notes being open to individual interpretation in preference to direct adaptation, with the only rule imposed being creators should stick to the original work, and not create sequels.

Only an extremely well read reader will be familiar with everything adapted, so for most surprises will be the order of the day. They’re found perhaps in Valerie Shrag’s erection-heavy take on Lysistrata, Vicki Nerino’s wild telling of a bawdy tale omitted from many Arabian Nights translations or Rebecca Dart’s imaginative Paradise Lost. As in all anthologies, some contributors disappoint while others rise above expectation. Without Kick’s preface, Molly Kiely’s Tale of Genji is only a series of delicate illustrations accompanied by meaningless text. On the other hand Rick Geary compacting the numerically dense fever dream ravings of ‘The Book of Revelations’ into a dozen remarkable pages is astonishing. Michael Lagocki drawing an excerpt from Virgil’s Aenid as if a superhero battle is a questionable decision, while Shawn Cheng illustrating characters from The Water Margin as if trading cards is inspired.

A single favourite? Well Robert Crumb’s excerpts of James Boswell’s London Journal ranks above almost all other contributors for technical accomplishment, but it’s found in his Weirdo collection. Robert Berry’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 (“Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day”) is a melancholy reinterpretation, individual and inspirational, with the delicate colours from Josh Levitas raising it higher.

The sample art combines humanity’s creation from Popol Vuh by Roberta Gregory and Edie Fake illustrating the visions of St Teresa. That one follows the other is an indication of the broad stylistic range. Kick’s sensibilities wander far from mainstream comics, so anyone unable to appreciate anything beyond a figurative naturalism to their comic art may not get along with The Graphic Canon. Even allowing for that, Kick preferring enthusiasm to talent results in several poorly created inclusions, but good well outweighs that, and ambition counts heavily. Volume 2 picks up with Kubla Khan.