Review by Frank Plowright

By 1981 Robert Crumb’s stock had dropped from his 1960s and early 1970s peak, as suggested by a strip referring to his continuing relevancy questioned during an interview by High Times. Looking to generate some creative impetus Crumb realised he’d never maintain a regular schedule for any magazine he had to fill himself, but editing an anthology could present his own work surrounded with contributions from others. The resulting Weirdo cultivated a deliberately trashy aesthetic, Crumb’s tastes individual and far from universal. As an example, The Weirdo Years includes the photostrips Crumb so loved, yet the readers, able to find something to admire in the most awkward of outsider contributions, were united in hating them.

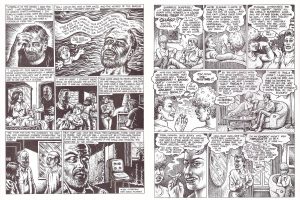

They’re the least of what’s on offer, as Weirdo provided a venue for Crumb to explore his own interests unconcerned about page count or pleasing a publisher or an audience. Overall this has an incredible range, encompassing gag illustrations, all 28 covers Crumb produced with their detailed frames, and those damn photostrips. All that’s even before considering the strips, some of which rank among Crumb’s best work. Many are personal, Crumb speaking directly to the audience, whether satirically in ‘I Remember the Sixties’ or opening his heart and mind in ‘Uncle Bob’s Mid-Life Crisis’, and the subsequent apologia ‘I’m Grateful, I’m Grateful’. Many autobiographical pieces are produced in the company of wife Aline Kominsky-Crumb, her less accomplished art an interesting reflection of her more accomplished personality. Domestic harmony and parenting issues may not have been what people expected from Crumb, but these remain compelling for Crumb’s utter honesty about his compulsions, ‘Footsy’ a strip set in high school detailing their beginnings. For all the introspection on offer, the constant conflict of desire and opprobrium, time has proved Crumb never changes.

The nearest Crumb comes to a series is the scattershot observations about shallow 1980s ideals in ‘Mode O’Day and Pals’, Crumb attempting to merge his own deliberately old-fashioned inclinations with the spiky 1980s look. The idea of what’s in effect a sitcom is strangely experimental territory for Crumb, but largely transient slapstick, a grumpy old man shooting fish in a barrel.

Adaptations were something new for Crumb in the 1980s, not entire works, but snippets ranging from the joyous illustration of song lyrics to the darkness of Philip K. Dick describing his hallucinatory visions. Crumb lights upon the prurient, among others adapting a portion of James Boswell’s 18th century diaries, Kraft-Ebbing’s astonishing late 19th century categorisation of sexual fetishes, and the cautionary fairy tale ‘Mother Hulda’. They’re very different, yet each has Crumb bringing something of himself to the table, be it the leering Boswell or the fairy tale’s peasant girl being the archetypal Crumb fantasy woman.

Two of Crumb’s most infamous strips close the collection, intended as satirical representations of paranoid right wing nightmares, yet provocatively and uncompromisingly titled. That one was subsequently co-opted by a right wing magazine shows how utterly misguided these strips are, and the more time passes, the more they disturb.

Is there another creator capable of producing the wide-ranging content to such high standards? That’s a rhetorical question. Even a comparative throwaway strip bemoaning the progress of pop music is packed with beautiful illustrations, many of a raging Crumb. Perhaps Limahl’s eventual immortality will be his representing the vacant 1980s pretty boy pop star in a Crumb strip.

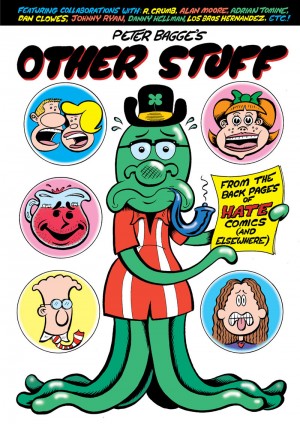

Anyone interested in reading more about Weirdo and the contributors who surrounded Crumb’s work is directed to Jon B. Cooke’s excellent and exhaustive The Book of Weirdo, featuring a new Crumb interview and comments from almost everybody whose work appeared in the 28 issues.