Review by Frank Plowright

These aren’t Superman’s absolute earliest appearances, which are collected in the Action Comics Archives, but seeing as this compiles the first four issues of Superman’s own comic starting in 1939, they represent near enough the dawn of the superhero era. It’s now almost impossible to convincingly imagine an era where Superman had only been around for a year, much less 64 page comics for ten cents, and the historical and cultural importance of the earliest Superman stories is immense. However, Superman’s history, and that of superheroes in general, is one of small steps, and this is a very different Superman in a very different world. He’s the guy who leaps buildings in a single bound rather than flying above them, and can still be knocked unconscious by an exploding bomb, but as seen several times, bullets just bounce off him.

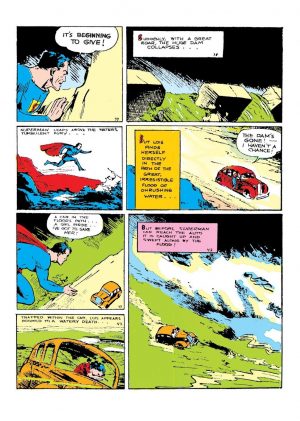

Superman’s first issue is mostly reprints from the first few issues of Action Comics, but an interesting bonus is DC also including the ad pages from inside and back covers for that and other issues. This early in Superman’s career he’s not fighting super-villains, or saving the planet, and in that sense there’s a greater humanity to him. He uses his powers to intervene in people’s lives, improving them or saving them, and while he does fight crimes, and there are gangsters, they’re anonymous with generic names. That is until what’s only the second appearance of Lex Luthor, referred to as “the mad scientist” in the fourth issue. He’s slightly less generic than other threats in his testing of Superman, and Paul Cassidy’s art is a slightly more polished version of Shuster’s basic style. The best story here has Superman dealing with a burst dam as Shuster pulls out all the stops. He always shows Superman full figure when in action, and set against the scenery fighting the sheet power of massed water in larger panels provides the spectacle other stories don’t.

Siegel and Shuster originally intended Superman for newspaper strip publication, and their strips have the pacing required for a daily strip, the scenes brief bursts, and the panels sometimes individually numbered. It can also be seen how famous newspaper strips of the time provide inspiration, with boxing, orphans and murder mysteries featured. These stories even pre-date thought balloons, thoughts appearing in dialogue balloons with the edges perforated, or beneath the dialogue in brackets and quotations. The past is displayed as a different country. Superman’s life has always been intended as astonishing, but from a distance of eighty years these stories frequently astonish for unintended reasons. Gassing a monkey as a demonstration for a journalist is perfectly acceptable, Lois Lane is demoted to the “lovelorn column”, and the use of some words has radically changed since 1939.

A crude energy is present, and by today’s standards slightly more imaginative thoughts are appearing by the fourth issue, but because of what Superman has become we’re no longer as impressed by him running faster than an express train, a repeated gimmick here. Siegel and Shuster’s creation can be contextualised, but they took a conceptual leap. However, while in no way excusing their despicable exploitation, the truth is that other creators could produce better Superman stories, and this material is now only of historical interest.

These stories have subsequently seen print in several other formats. In the paperback chronological reprinting of all Superman stories they’re found in Superman Chronicles Volumes One, Two and Three, or in Superman: The Golden Age 1 and 2. They’re also in luxury format Superman: The Golden Age Omnibus. Vol. 2 contains another sixteen early stories.