Review by Karl Verhoven

The title would have you believe The Walking Dead is about zombies. In a way it is. They’re a persistent background presence, a constant danger if encountered in bulk, and the necessity that prods the plots. What this really is, though, is a drama about a pocket of humanity surviving under extreme conditions, and a questioning of who the walking dead might really be. In that fashion, the TV series follows the pattern of the books very closely. Indeed, the first three seasons pull most of their plots directly from the graphic novels.

The entry point is Rick Grimes, a police officer injured in the line of duty who awakes in a hospital bed. He’s alone, but immediately discovers the world has changed as he lay comatose. He works his way through the zombies, learning as he goes, and by the end of the opening arc he’s located a group of other survivors, camping outside Atlanta.

Cities are over-run with zombies, so pretty well off-limits, and with winter coming, more substantial shelter is the order of the day. The group first decamps to a farm, then to an abandoned prison, while a town with some protection is also featured.

Writer Robert Kirkman is surprisingly good from the opening chapters, and improves as the book continues. His characterisation is strong, his plotting exceptional, and his ideas impress. He maintains an admirably unsentimental attitude toward his cast, and “don’t become too attached” is pretty well a rule here. Kirkman is also excellent at maintaining tension, pulling the rug from expectation, and throwing in one immense shock every few chapters.

Grimes remains the lead character throughout. He opens the book, and he’s featured in the final panel, between which very much has changed. Among those altered aspects is Grimes, initially an upstanding paragon of virtue, clinging to his old police training, but eventually a man who’ll do what’s required to remain alive, however distasteful that may be to himself and others. By the midway point he’s explaining “Things have changed. The world has changed, and we’re going to have to change with it.” Just in case it’s a concern, it’s not explained here exactly how the zombies came about. Go with the flow.

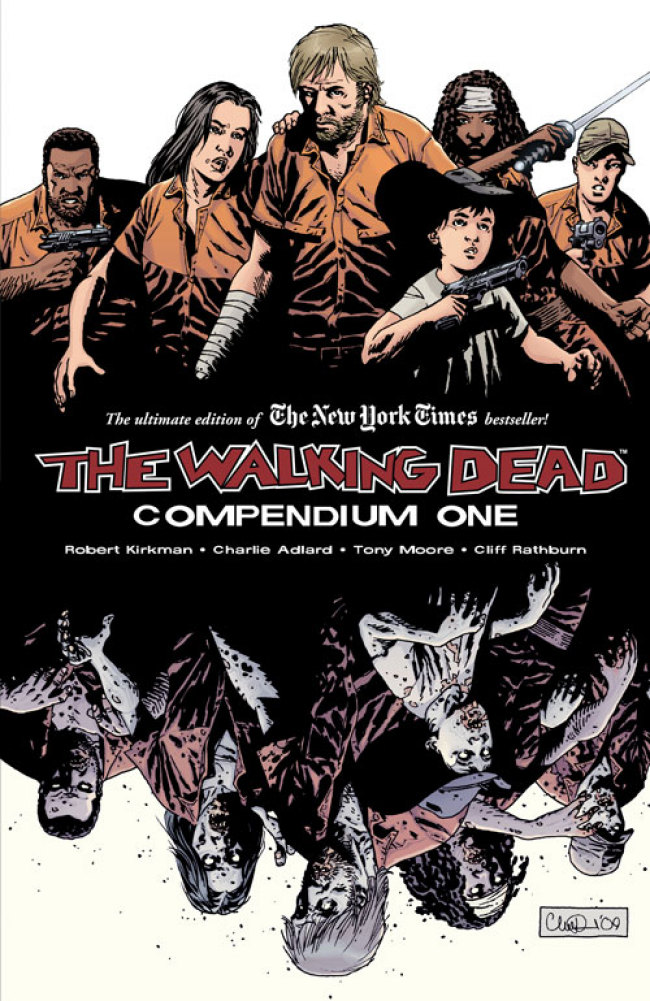

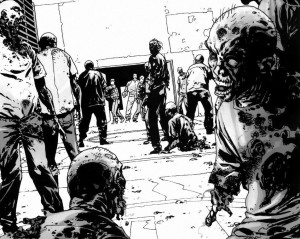

Most of the book is drawn by Charlie Adlard, whose application is possibly under-rated. He has to distinguish a large ensemble cast, illustrate them just talking for prolonged sequences and populate his issues with, at the very least, dozens of shambling zombies. There’s never a lack of clarity, never any dodgy figurework, and never a problem identifying a character. His art is modified by the greytones of colourist Cliff Rathburn, but their application is largely a statement of style, as they add little to the art. They’re absent from the opening sequence, illustrated by Tony Moore, who has a less naturalistic approach, but provides more detailed pages.

The hefty cover price may seem offputting, but it’s exceptional value when compared to buying eight individual paperbacks, or four hardback volumes collecting the same material. You’ll even save money by buying a couple of the slim paperbacks books as samples, then coming back to this compendium if you enjoy them. The original books are titled Days Gone By, Miles Behind Us, Safety Behind Bars, The Heart’s Desire, The Best Defense, This Sorrowful Life, The Calm Before and Made to Suffer. The zombies shamble further in volume two.