Review by Karl Verhoven

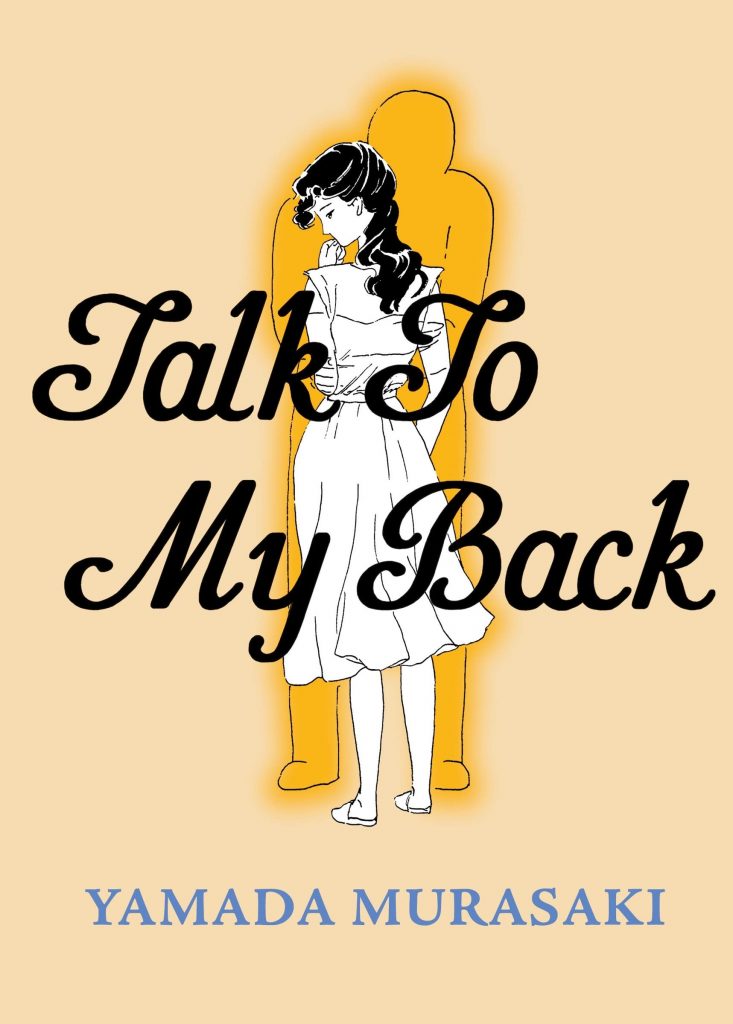

The more time passes, the more Yamada Murasaki’s comics have been valued and accorded an importance in Japan. In the late 1960s she emerged among a group of women creators given a venue by Osamu Tezuka’s COM magazine, circumventing many difficulties women had previously experienced. However, she conformed to the expectations of 1970s Japanese society when she married, and spent five years away from comics when starting a family, but the marriage was problematical, and she felt trapped. Although she returned to comics before separating from her husband, Talk To My Back only began serialisation in 1981 when they were no longer living together. An extensive biographical essay by Ryan Stromberg supplies not only the details of her life, but her influences, and an analysis of her work.

Talk To My Back is ostensibly a collection of short stories meditating on the feelings of being a mother and housewife. They can be read individually, but build collectively, into quite the indictment of social expectations and reiterate the adage that no-one knows what goes on behind closed doors.

There’s a subtlety that may not be apparent to 21st century readers. The lack of satisfaction and doubts expressed through the young wife of the story, Mrs. Yamakawa, relate to the expectations placed on women. A chapter titled ‘Walking On My Own’ has the wife leaving on a rare night out, unable to shake the feeling that she’s forgotten something. It eventually dawns that she’s only ever outside the home accompanied by her children, and there’s an immense sense of freedom derived from their absence. It’s giving voice to something so many women at the time must have felt, and is a wistful reflection topped off with a crisis at home when she returns.

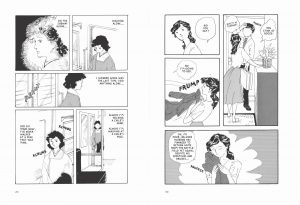

Self-awareness and poignant observation are frequent. Telling her children a story about her youth, Mrs. Yamakawa reflects “I’ll probably end up telling this story so often they’ll groan with boredom”, concluding with the thought that she intends to continue telling it until she’s bored with it. The seeming lightness of the writing having hidden depths is repeated in the illustrations, looking very simple at first glance, but emotionally strong and extremely expressive. This often uses repression, Yamada not showing very strong feelings via the face, which is cut off at the top of a panel.

How much her personal antipathies affect the portrayal of the husband is unknowable, but just like Yamada’s husband he drinks too much, and by Western standards he’s an entitled jerk with little understanding. “In front of me sits a man who can only see his wife’s health in relation to his own convenience” she notes at one point. Did all Japanese men of the era consider a marriage ring bought them a servant as well as a wife?

Honesty would drown in a tirade of righteous anger, so it should be stressed that for all the importance of the message, it’s coated in reminiscences about children growing up, gentle humour and a wealth of charming day to day moments. It makes for a bittersweet, but always compelling experience.

The obvious question that arises is to wonder how much life for the married Japanese woman has progressed since Talk To My Back was first published. Greatly, one hopes.