Review by Frank Plowright

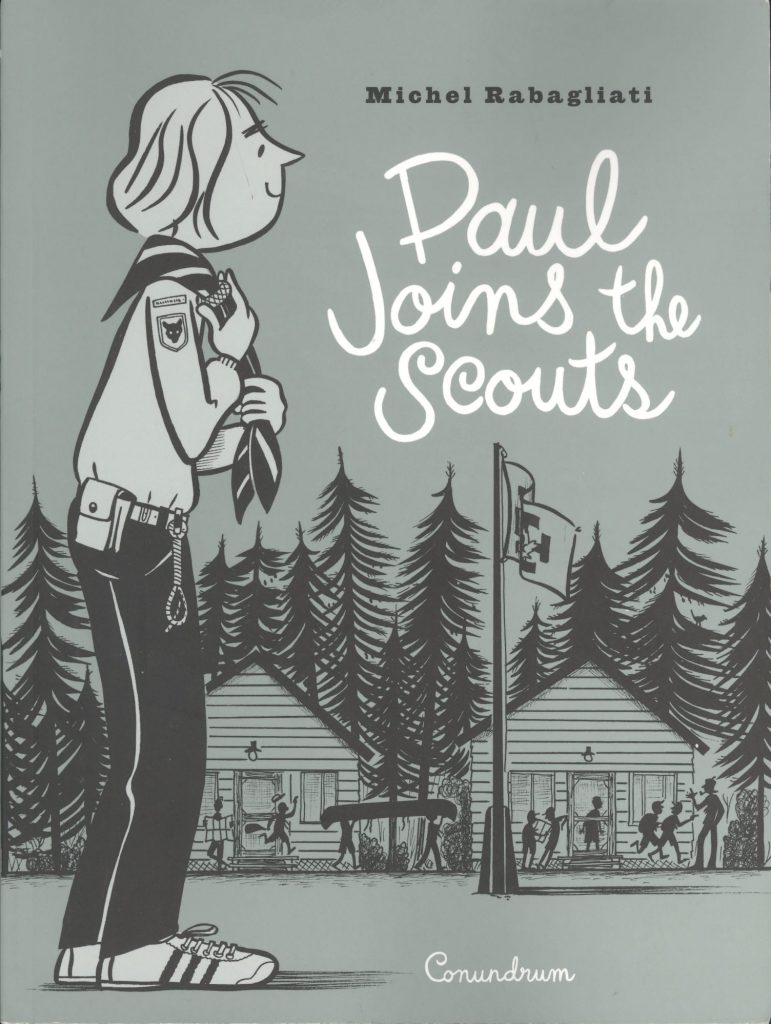

Since the late 1960s there’s been a movement for independence from Canada in the French speaking province of Quebec. Spearheaded by the FLQ, it was at its most radical when Michel Rabagliati was approaching his teens. It’s the time he returns to via alter-ego Paul, who begins unsure of whether or not he should join the cub scouts, and is also just taking his first faltering steps into creating comics.

Instead of concentrating on one subject, Rabagliati floats around his topics of interest, covering kites, his first tentative friendship with girls, comics, playing guitar, and what the cubs can offer. It’s the experiences with the cubs that come to dominate, and each of the officers is allocated a headed segment in the form of brief speculative drama. A regular joy of Rabagliati’s books is the piecemeal way he discloses aspects of his youth, and here it’s the discovery in the school library of a book that eventually led him to his own first comics. We’ve already seen how the young Paul treasures André Franquin’s Gaston strip, and it’s Franquin’s book with Jijé about how to produce comics that opens a door.

Events are largely linear, covering 1969 to 1971. We meet the people Paul associates with, and there’s an observation or reminiscence about all of them, something that still stands out over forty years later. It’s the country bus tour, stopping off where and when its necessary, irrespective of any bigger picture. For most of the book, the FLQ, for instance, aren’t any kind of dramatic counterpoint, but something the young Paul and his cub friends are attempting to figure out with limited context and the occasional adult input. Toward the end Rabagliati examines them more thoroughly (in brief), and they do adjoin his personal recollections.

There are ties between this and three other Rabagliati books. The most obvious is with an earlier book looking at a period eight years later in Paul’s life. Here he’s a cub scout discovering summer camp, and in Paul Has a Summer Job he’s one of the teenage camp supervisors. The more mature raconteur can now admit he wasn’t able to supply the inspiration he’d earlier received. It’s the storytelling technique of blindsiding readers that connects with Paul Goes Fishing, and in the later Paul at Home, Rabagliati considers the creative process for this book, noting he started it intending to experiment with his art and adopt a looser style. He concluded it wasn’t him, and returned to what we’re familiar with, and should cherish.

While Paul Joins the Scouts provides all the strengths and insights expected from Rabagliati’s work, too many pages are allocated to scout camp activities, which occupy around a sixth of the page count. They’re joyously illustrated, and are obviously significant memories of halcyon days, but don’t engage in the same way as the pages describing the complicated family living arrangements and consequent tensions, or Paul’s introduction to dating. There’s a narrative purpose to the extended focus, explaining the personalities and highlighting the bonds made, but that’s only clarified right near the hammer blow end, and while no pages by Rabagliati are ordinary, until the pay-off, this sequence drags.

That comment apart, this is infused with the same gentle sentimentality, and polished illustrative storytelling and for those caught up in Paul’s life, there’s considerably more information about family members.