Review by Frank Plowright

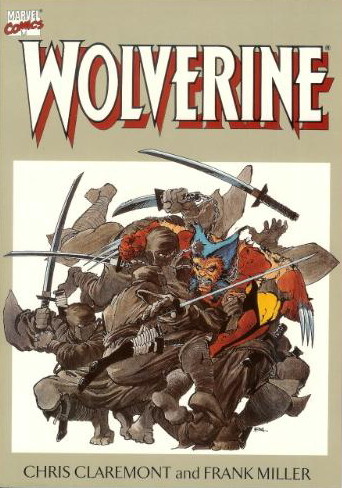

With the passing of time it’s almost impossible to convey the sense of anticipation and excitement this story generated when first announced. In 1982 Chris Claremont was unquestionably the fan favourite among Marvel’s writers, Frank Miller was equally acclaimed for his gritty, revisionist interpretation of Daredevil, and Wolverine had long been the standout character in the X-Men. This was well before everyone and their mother had created a Wolverine one-shot, in the days when Marvel’s approach to launching a character in their own title was far more considered.

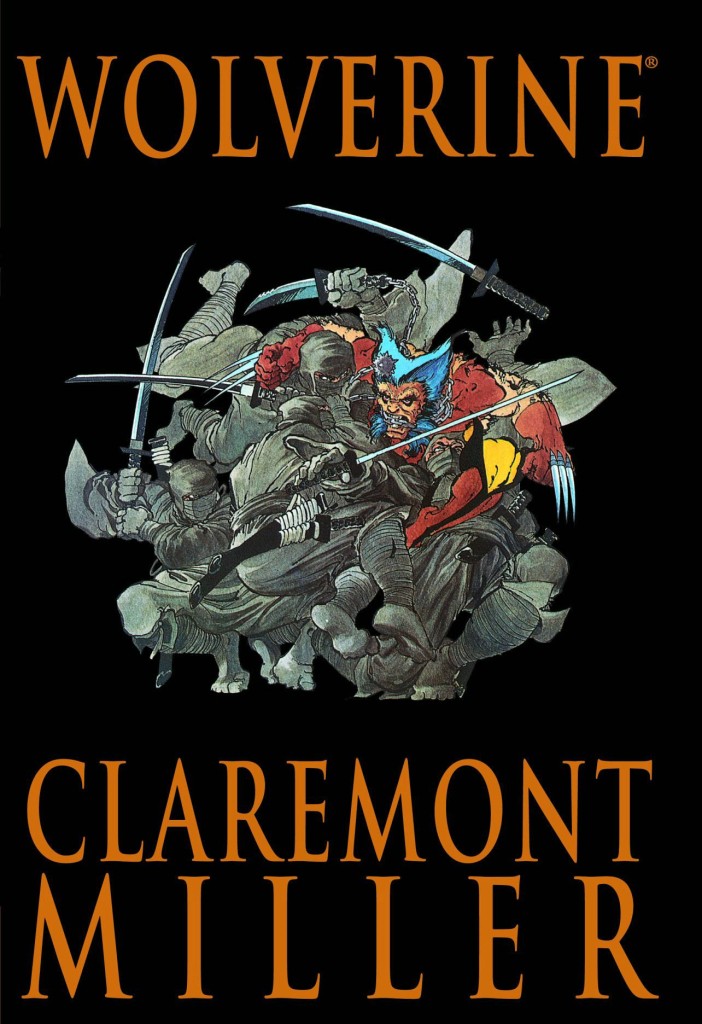

Credit to Claremont, he could have played to type and delivered the pint-size bezerker that’s been seen so often since. He could have delved into what was at that point still Wolverine’s mysterious origin. Instead he toyed with the idea of Wolverine as a failed samurai, and that hook attracted Miller to the project.

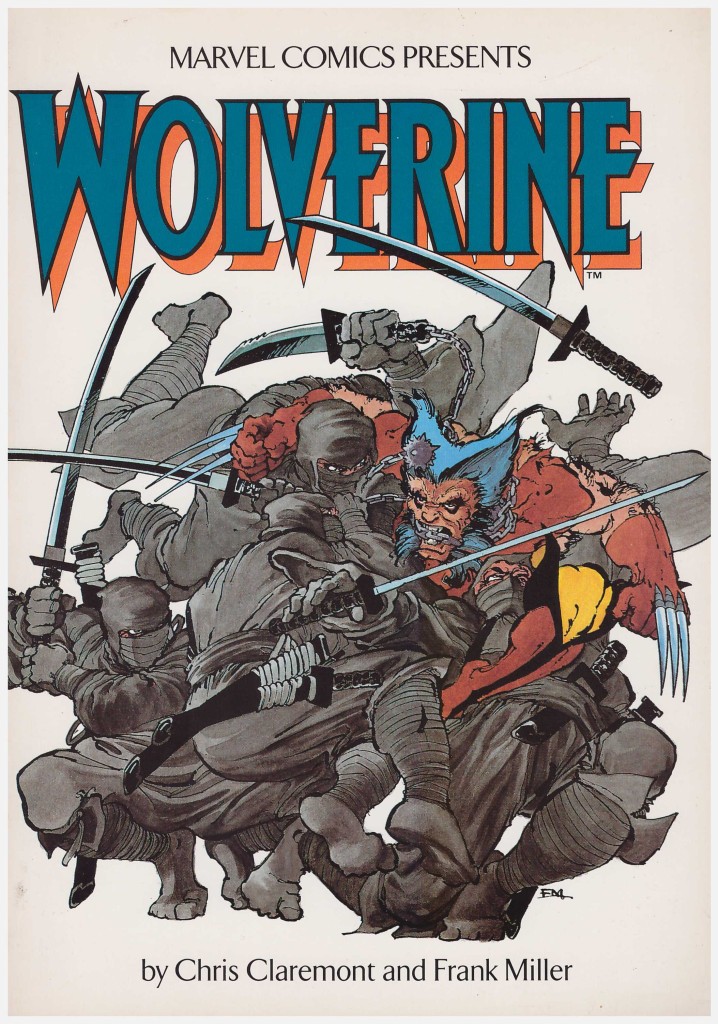

The opening sequence is an excellent definition of Wolverine. His heightened senses have enabled him to track a wounded bear to its cave. In its pain and confusion it’s slaughtered several innocents, and once he’s dealt with the bear, Wolverine sets about the hunter who left it in that condition. Variations on this have been done to death since, but give the original some credit. The inconvenience of obligation trumping love in Japanese society then raises its head as he learns his girlfriend Mariko has been married in settlement of her father’s obligations.

Lord Shingen heads the Clan Yashida, and is engaged in uniting the Japanese underworld. An initial encounter is cleverly rigged with the purpose of demeaning Wolverine in Mariko’s eyes, and he plays into it. From there the tale follows the classic pattern of Japanese myths in which the disgraced warrior seeks redemption.

In 1982 this was new to almost all the readership, as was Miller’s remarkable adoption of classic manga art stylings to illustrate the story, and the idea of Wolverine beset by ninjas. Miller was strongly influenced by Lone Wolf and Cub, then unavailable in English, but brought his own sensibilities to the table, and turns in some magnificent pages and imaginative layouts. A few rough edges evident in his Daredevil art at this stage were smoothed by inker Joe Rubinstein. Claremont’s writing has no rectifier, and as such is the element that prevents this remaining five star material. The plot ebbs and flows well, but the captions and dialogue are of their era, expository and over-written, yet not to the point where they stunt the thrill of the art.

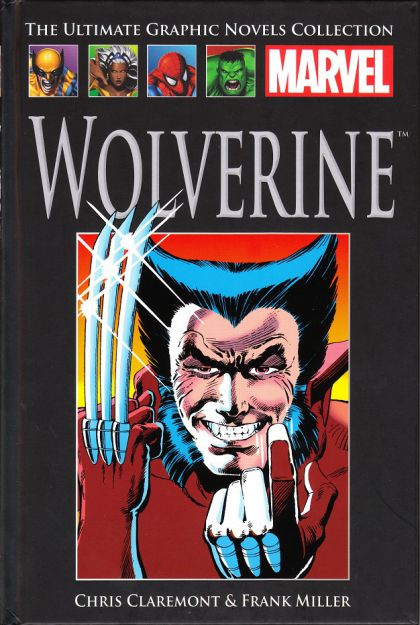

Later editions, including the recent UK Hachette volume in their Ultimate Graphic Novels Collection, add a couple of chapters by Claremont and Paul Smith originating from the X-Men, and following up on the Miller illustrated story. While that may seem a welcome bonus, it’s a mistake. This is decent X-Men material, and Smith a good artist, but they were prepared for a different audience, and suck the power from the Miller material. That was Wolverine in his own milieu, unencumbered by the weight of continuity. These chapters are soaked in it. Don’t bother with them, or read them instead in X-Men: From the Ashes. Alternatively everything here is gathered in volume nine of Marvel Masterworks: The Uncanny X-Men or the third Uncanny X-Men Omnibus.

It was a couple of decades before there was another Wolverine story to match this, and it still stands as thoughtful and viscerally exciting.