Review by Frank Plowright

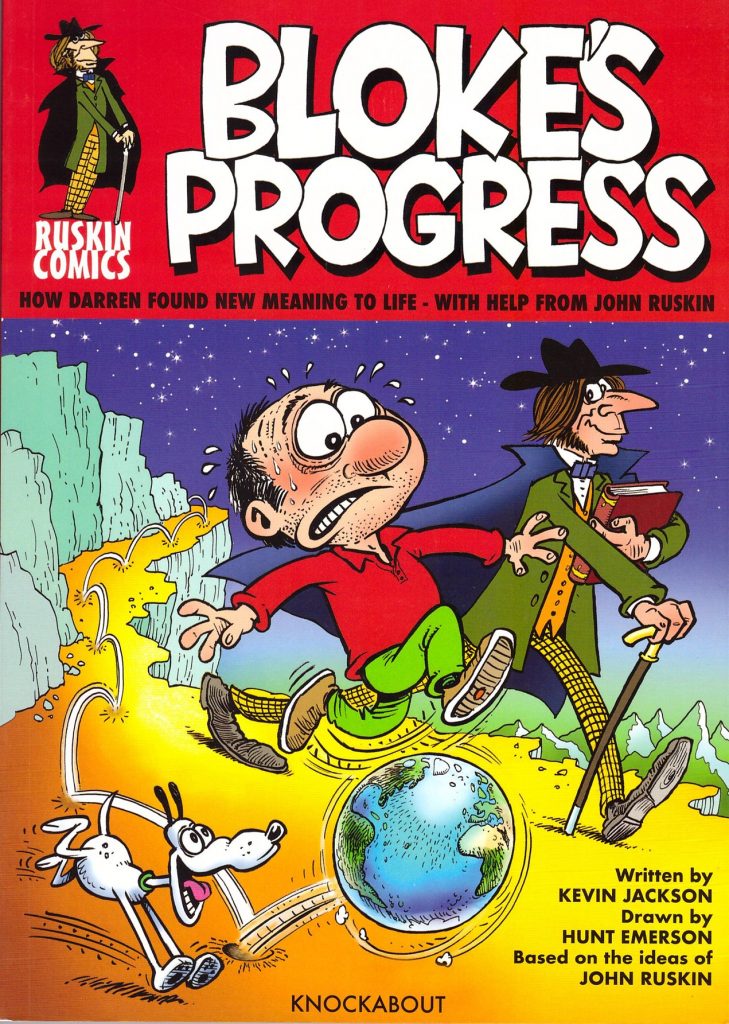

The 21st century hasn’t been kind to John Ruskin, what with TV drama and film reducing him to an asexual prig, his art criticism downgraded by virtue of his own work being re-evaluated, and the philosophies that influenced the influential of the late 1800s reduced to academia. It continues a path begun shortly before his death in 1900, when he was considered to have descended into lunacy. There’s no little irony in this plea for a restored reputation being presented by Britain’s greatest living humour cartoonist.

Hunt Emerson is working with Kevin Jackson who provides an informative four page introduction explaining just how influential, radical and knowledgeable Ruskin was over an astonishing variety of disciplines. A glib modern day comparison might be Stephen Fry, but as entertaining and informative as he is, none of Fry’s books or documentaries have changed society. Ruskin did, and his thoughts on wealth, seeing things and work are explained over three chapters to lottery winner Darren Bloke, who’s discovered instant riches aren’t the solution to all personal problems.

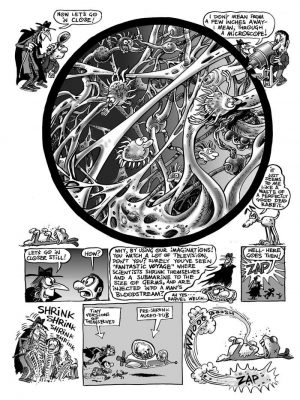

In the interests of full disclosure, The Ruskin Foundation are involved, and Bloke’s Progress began when Jackson and Emerson were commissioned to produce comics for distribution to British schools and prisons. Modern day comparisons and examples are used to convey Ruskin’s ideas, and Emerson’s always excelled at sneaking real world horrors into his stories when necessary, which works again, as does an even greater talent for sneaking little visual gags into his pages. These may seem a distraction, but could also be seen as cementing the message by ensuring longer is spent looking at the pages, which illustrates one of Ruskin’s points. We may not all be wealthy or creative, but almost all of us have sight, and if we spent more time looking at the everyday our perceptions would broaden. Ford Madox Brown’s painting Work is hardly everyday, but the dissection of it and a modern day recreation by Emerson illustrate Ruskin’s point of looking deeper exceptionally well, while simultaneously distilling his ideas of wealth and work, and incorporating his art criticism. It’s very clever.

The combination of important and still valid ideas easily explained, the restoration of a reputation and great cartooning take Bloke’s Progress a long way, but it’s a little limited by the repetitive formula of Darren being led by the nose, required for the original educational market. Jackson does address common accusations levelled at Ruskin, the most frequent being that someone born into a wealthy family isn’t entitled to pontificate on the subject of work. Also taken into account is that basic human nature changes very little, so although Ruskin lived in Victorian times, Jackson and Emerson can simply apply his thoughts to the current world. Ultimately, it’s difficult to imagine anyone with a curious mind not wanting to learn more about Ruskin after reading Bloke’s Progress, and that would have been the creative intention.