Review by Frank Plowright

An extremely impressive wistful melancholy infused the first part of this story, with Valerian and Laureline separated by millions of miles and a few thousand years. Châtelet Station explained how they were both searching for clues as to why there were anachronistic manifestations in the Paris of 1980. Laureline’s 23rd century research discovered that the primal forces of fire, water, earth and air had been abducted from their shrine on a remote planet.

The thieves, about whom we learn more here, have concocted an ambitious scheme to prise money from big corporations in the 1980s, arranging displays of power using the stolen forces. Valerian has already subverted two of them.

As fully revealed, Pierre Christin’s plot depends on lapses of logic. The thieves are displayed as idiots throughout, and there’s not a clue as to how they accessed the technology to contact people in the past, supposedly severely restricted. Beyond that, wouldn’t there be simpler ways for them to acquire enormous riches from the stolen elements in their own time? Furthermore, Christin takes a scattershot approach to his scornful view of those exploiting pre-millennial tension. The good, though, outweighs the bad if the mood is taken into account.

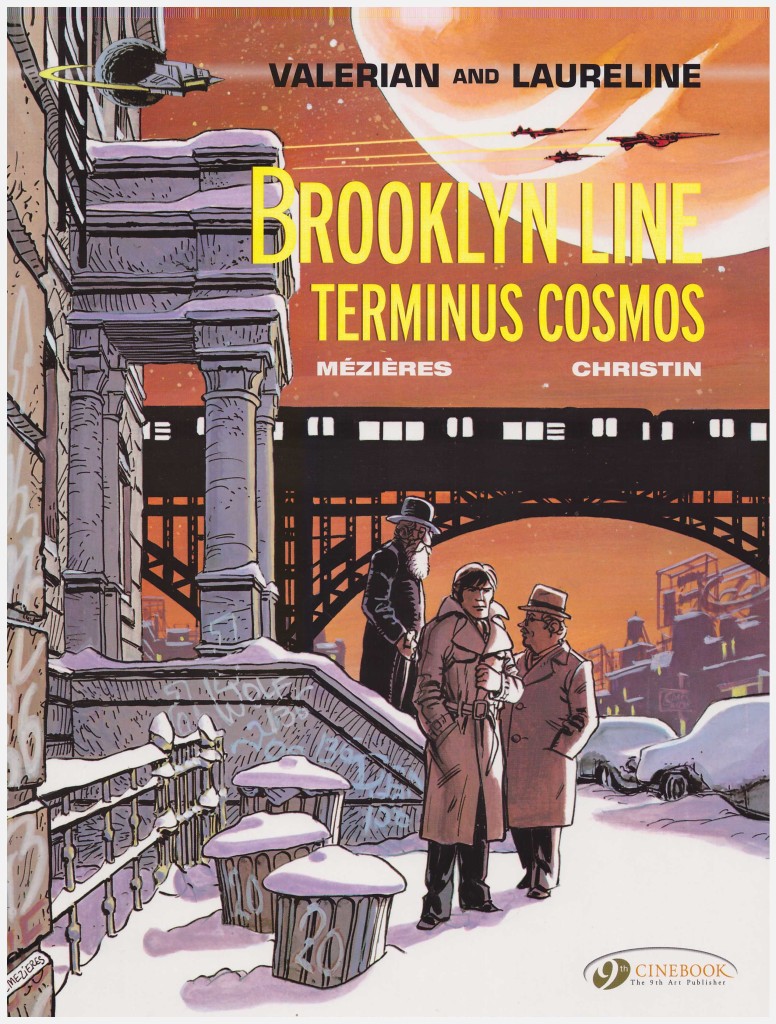

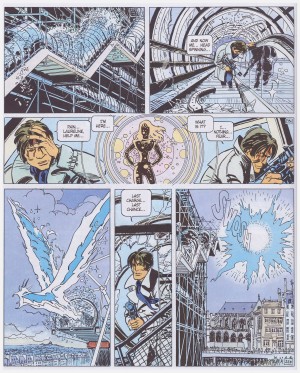

An increasingly jaded, confused and exhausted Valerian is far from the infallible heroic figure usually populating such fiction, and his strain is excellently conveyed by Jean-Claude Mézières as he slumps in cars and planes. Mézières was obviously at home in depicting 1980s Paris, but his version of Brooklyn, where one portion of the story concludes, is equally redolent. From the beginning of the series the imaginative flowing detail with which he constructs the future has been marvellous, and Mézières refined that approach to excise the clutter. There’s a superbly evocative contrast between the 1980s and Laureline’s journey in the future.

Christin’s plot has a capricious, but creative ending with Laureline again at the forefront. While there’d been some capable space heroines of the future in French graphic novels previously (Barbarella for one), Christin was well ahead of the times in his portrayal of Laureline as an equal partner.

As with the previous book, Christin allows himself some discussion as to portents of the future, rather chilling in the light of the series’ opening book, referenced here. Albert, the Galaxity’s agent in 1980s is an engaging and curious chap, and well matched with his American friend Schlomo Meilshem, if anything even more erudite. Christin’s obviously fond of Albert, who returns immediately in the following graphic novel The Ghosts of Inverloch.

While flawed, and disappointing in relation to the set up in Châtelet Station, there’s still much to recommend Brooklyn Line from its downbeat mood to ingenious conclusion. The events, discussions and introductions have a long-lasting repercussions for the series as a whole.