Review by Karl Verhoven

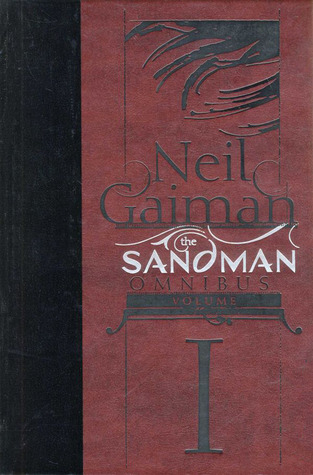

A problem with many Omnibus collections is the lack of thought applied to the production possibilities. That’s not the case for Sandman. This volume is a handsomely designed, faux leather production with foil lettering. It looks better than any other Marvel or DC Omnibus to date, only fitting for what’s proved a perennial fantasy discovery for each new generation, conceived by a writer who’s become a genre Titan.

To the uninitiated, Sandman, or Morpheus, or Dream as he’s known to his six siblings, is the Lord of the Dream Realm, a manifestly powerful being who nonetheless begins the series having been trapped by an occult dabbler for seventy years. This has consequences.

Surprises still await after all these years when reading Neil Gaiman’s stories again, and that’s always pleasing. The first surprise is Sandman being intended as a horror series, and Gaiman uncomfortably straightjacketed by that, the earliest stories awkward, unformulated and thrashing around a little. To his credit, though, Gaiman adapted rapidly, and while the influence of Alan Moore is apparent during a convention for serial killers, it still shocks. A major surprise is what a dull character Sandman himself is, given to pompous authoritarian pronouncements, and distanced from almost everyone. It’s with the introduction of a whimsical, almost kindly version of Death that the series begins to take flight, a line perhaps drawn when she claims “He’s not my friend. He’s my brother, and he’s an idiot”. It’s from the having one’s cake and eating it school of characterisation, but effective, and Sandman’s supporting cast is thereafter packed with fascinating personalities. Several would progress to their own solo stories (by others).

Whether a step intended from the beginning, or something that occurred as Sandman continued, Gaiman creates a feature open to telling any type of story in any time or place. He gradually shifts the format from horror to fantasy, although it’s not until almost the end of this selection that the horror disappears entirely. It’s the trappings that hang around, but very effectively filtered. The use of Lucifer, again not as expected, finally sees the conventional horror off, but the statement has been made before then with an award-winning story about struggling travelling playwright William Shakespeare, the dream life of cats, capturing a muse, and a tragic superhero.

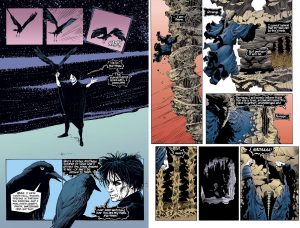

The artwork is as diverse as the writing, but equally patchy to begin with. First choice artist Sam Kieth didn’t feel he fitted, and his successor Mike Dringenberg is an artist of contrasts, sometimes awkward and unimaginative and sometimes thrilling in conveying the wonder. The series takes flight, though, with the realisation that a regular artist isn’t a necessity, and Gaiman begins considering the talents of each artist when constructing the story. The other sample art is from Kelley Jones, best known for his horror comics, but entirely at home with a different world. There’s no arguing with the talent of the assorted artists.

Once Gaiman finds his flow, he and his collaborators supply a series of human reflections, and a primary joy of Sandman becomes never knowing where Gaiman is heading next. Being unwilling to settle into conformity coupled with Gaiman’s imagination ensures this prolonged meditation on storytelling is now timeless.

This reprints Sandman as originally issued month by month, so differs from the paperback collections. Individually the content can be found in Preludes and Nocturnes, The Doll’s House, Dream Country, Season of Mists and A Game of You, with some content from Fables and Reflections. Reviews with greater emphasis on individual plots are located by following the links. Vol. II completes the original Sandman reprints.