Review by Frank Plowright

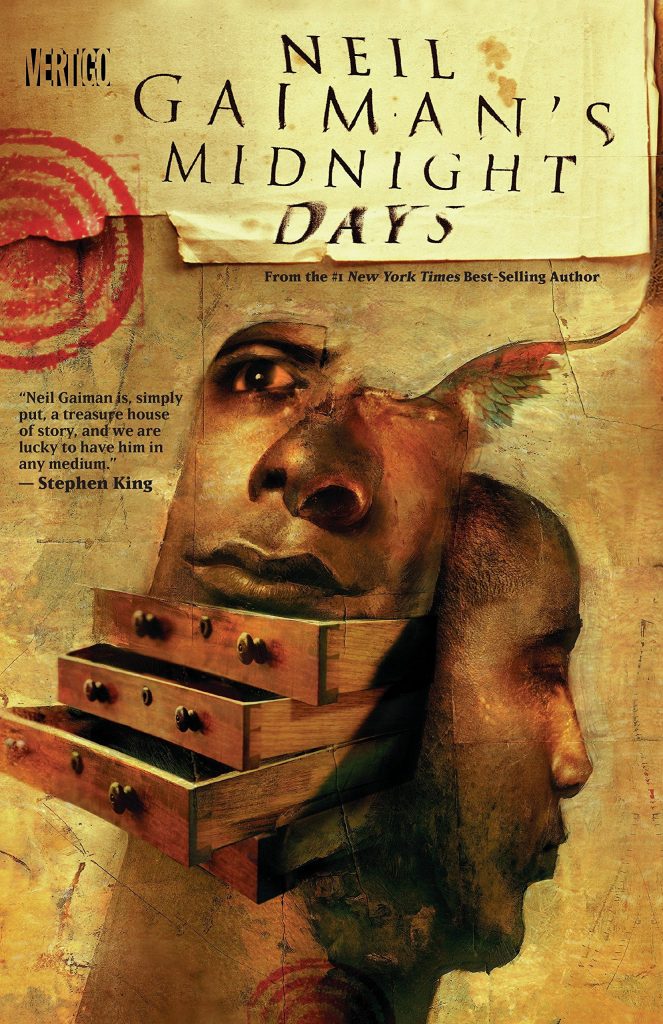

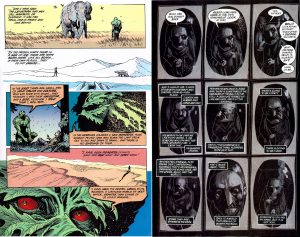

Neil Gaiman’s Midnight Days is a house clearing anthology gathering Gaiman’s one-off work for assorted Vertigo titles, with a major selling point being an early Swamp Thing script he wrote finally seeing print. It’s the opener, drawn by the classic 1980s Swamp Thing art team of Steve Bissette and John Totleben, and because Gaiman’s a good writer, it’s a good piece, but by his own standards it’s slim, the Swamp Thing of the 14th century comforting a dying victim of the plague.

Much of the collection skirts around the characters in whose titles they appeared, Swamp Thing subsequently reduced to cameos, Gaiman’s Sandman more deliberately so, but because what Gaiman is interested in transmits so well, this isn’t a criticism. As a 1960s schoolboy he was attracted by the plain weirdness of Brother Power the Geek, written by a creator in his fifties channelling hippy culture he didn’t understand. In 1990 Gaiman’s version of Brother Power is an idealistic remnant of earlier days, a failed elemental. It’s a disjointed tale, good in places, but thrashing around in others, although nicely drawn by Richard Piers Rayner and Mike Hoffman. Far more satisfying is the shorter story of the Floronic Man, denying he’s mad, but patently so en route to a meeting with ancient forces. Gaiman’s clever, apparently dissociative script is matched by the delicate beauty of Mike Mignola’s art.

Gaiman takes the trouble to write not only an anecdotal introduction to the collection, but one to each individual story, and his favourite among them features a weird night for John Constantine. Dave McKean’s loose and scratchy definitions surprise, and his sympathetically dark design for the unfortunate villain is tremendous, the inherent sorrow almost seeping off the page. Constantine, though, seems somehow too caring and fragile, a valid personality, just not his usual one in a type of tale Gaiman specialises in, where the validity is in the telling, not the plot.

The longest piece was plotted in collaboration with Matt Wagner, at the time writing the 1930s set crime series Sandman Mystery Theatre, only tenuously connected with Gaiman’s own Sandman title. Gaiman’s script is rich with cross-cultural observations between Americans and English folk, and surprises with sly little jokes, while he and Wagner have ensured the plot depends on Teddy Kristiansen’s art as much as any words. In places, this is a mistake as for all the mood he creates Kristiansen defines people via portraits, not as emotional personalities. Otherwise there’s a little too much explaining the plot, but it’s nicely unfurled from its wrappings to reveal itself as not far removed from a game of Cluedo.

Midnight Days ends with seven pages of comedy, originally the framing sequences in between which DC presented mystery stories by other creators. The script works well with the other material removed, drawn by Sergio Aragonés in his uniquely fussy and utterly adorable cartoon fashion. It’s farcical and funny.

Much of this work originates from relatively early in Gaiman’s career, the stumbling most apparent in the Brother Power tale, yet while that might be throwaway, most of the remainder stands up as enjoyable, if not perfect. The depth of Gaiman’s subsequent work is only apparent in flashes, especially in the Floronic Man and Sandman pieces, so don’t come to Midnight Days expecting latter day Gaiman and you’re likely to be pleased.