Review by Graham Johnstone

Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen stories began in 1898 with Dracula survivor Wilhelmina Murray (aka Mina Harker) enlisting colonial adventurer Allan Quatermain, and other colourful characters from Victorian fiction, to save the British Empire in its hour of need.

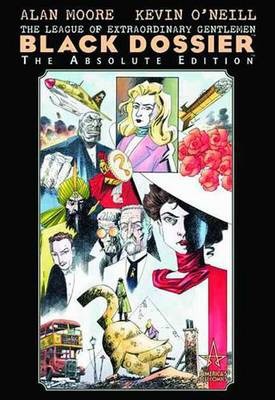

The Black Dossier was described by Moore as a ‘sourcebook’, and takes a wider look at this world where all fictions exist. A graphic novella is peppered with other comics and illustrated texts – the supposed contents of the British government’s dossier on the long history of the League.

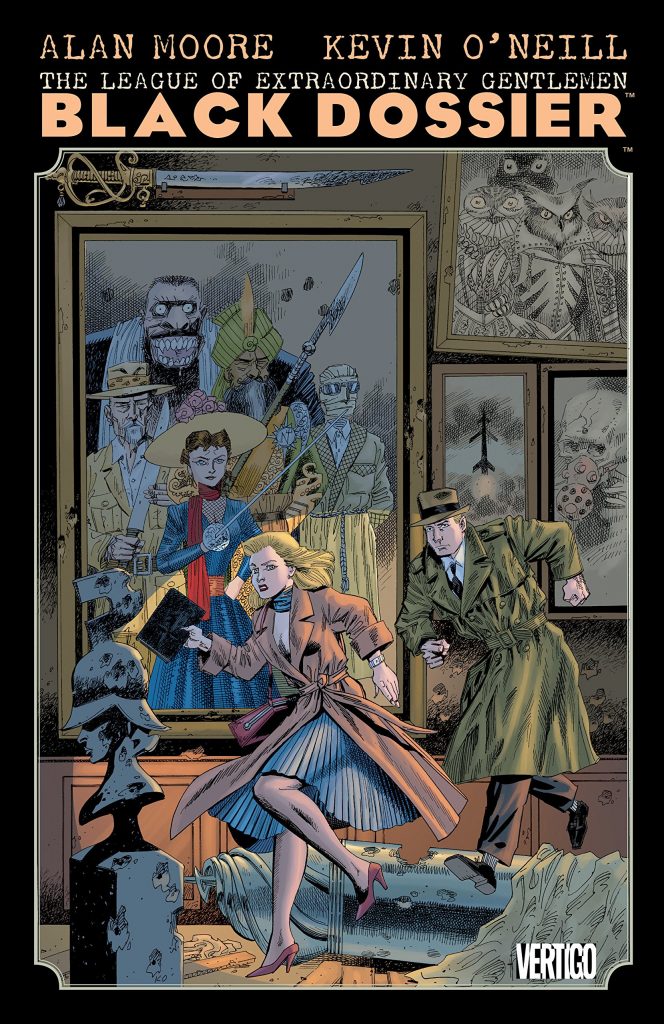

A framing story, set in 1958, has a still-youthful Mina and the supposed grandson of Quatermain steal the dossier. They scour the country seeking answers, while eluding agents sent to retrieve the stolen item. As with previous volumes, the promised ‘rousing adventure’ propels a travelogue of this composite fictional world. This one is an alternate history of a Britain still recovering from World War II, and the Orwellian Ingsoc government, while responding to the 1898 Martian invasion with a space programme. The intervening sixty years of backstory are deftly woven through the pacy plot and sparkling dialogue.

Moore’s necessarily oblique references to copyrighted characters further add to the fun. For example, government agent Emma Night plays on the maiden name of Mrs Peel from TV’s The Avengers, and ‘Jimmy’ is surely related to the League’s 1898 handler Campion Bond. Few will spot all the references, and they’re best treated like easter eggs in films and games – fun to spot, but no more necessary to appreciate the story than any other writers’ technique.

Playful plagiarism, though, masks savage satire. War profiteer Harry Lime is now a pillar of the British establishment, and self-styled ‘patriot’, Agent Drummond, revealed as a paternalistic xenophobe. Agent ‘Jimmy’ is equally amoral – a womaniser who won’t take no for an answer. Bested and bound by prey-turned-predator Mina, he attempts to shoot her from his mouth with a pen-gun that, Mina quips, might work “in ten years”. Moore’s chronology is as clinical as his debunking of a dubious hero.

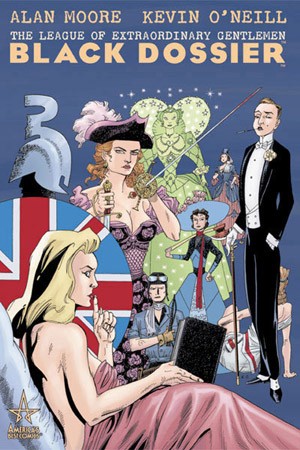

The fictional dossier’s contents extend the scope of the intertextual world-building through time, around the world, and into other worlds. ‘On the Descent of Gods’, credited to Oliver Haddo, weaves together myths and the fictional prehistories of H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. ‘Faerie’s Fortunes Founded’, reveals the formation of the League by Shakespeare’s sorcerer Prospero, and introduces Virginia Woolf’s immortal transexual Orlando. ‘The Life of Orlando’ extends Woolf’s ‘biography’ of the character back to 1260 BC, and forward to World War II. Mina and Allan discuss the files as they read them, so providing commentary on the often unreliable accounts. The research, imagination, and stylistic versatility is staggering. Intertextual fiction is common, but not on this scale.

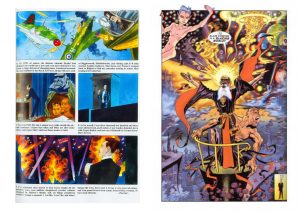

Kevin O’Neill’s illustrative skills have been honed over decades, and his depiction of this alternate 1950s does not disappoint, and in visualising the dossier’s historic files he demonstrates unforeseen range and versatility. His pastiche of Look and Learn’s educational comics on ‘The Life of Orlando’ (pictured, left) impresses, but the highlight is the saucy mock-engravings of the Fanny Hill romp. Letterer/designer Todd Klein impresses with period appropriate typefaces and yellowed newsprint effects. A further visual highlight ends the framing story, which realises the experience of alternate reality The Blazing World (pictured, right), with O’Neill’s art rendered into 3D by maestro Ray Zone.

The quantity of text pieces adds up to a demanding read, but The Black Dossier repays the effort, while Murray, Quatermain, and Orlando return in third volume proper Century.