Review by Frank Plowright

Spoilers in review

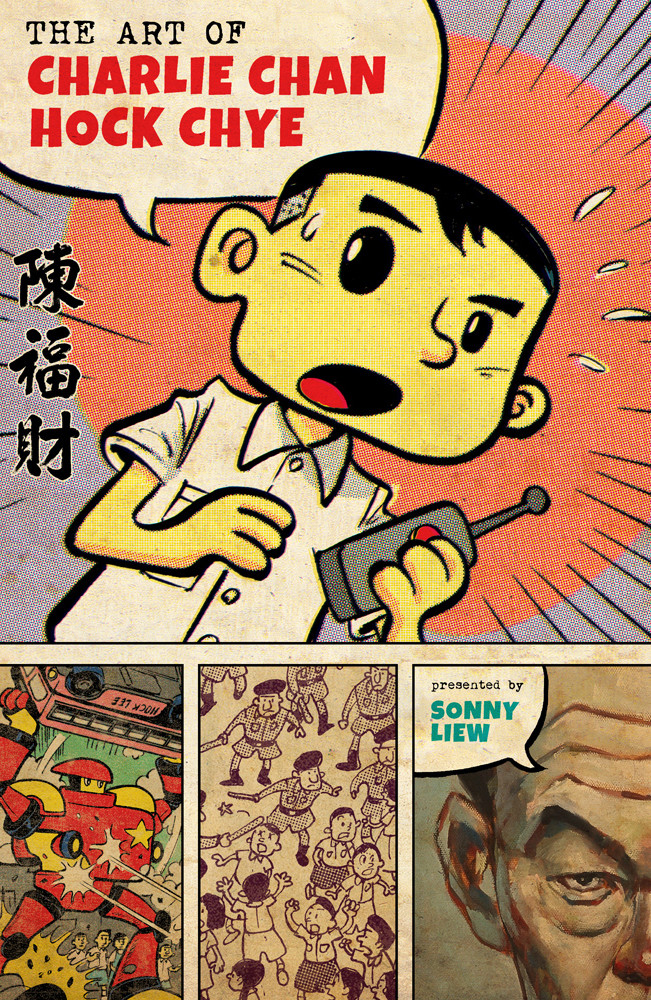

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye is a magnificent graphic novel, purporting to be a biography, but actually a critical history of Singapore from World War II onward, yet still delivering on the career of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. Sonny Liew charts a prominent Singapore comic artist, also supplying a history of the nation as interpreted by Chye’s work, and the result is fascinating, revelatory and compelling.

However, there’s a conceit best not disclosed, but it’s so central to The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye that omitting all mention would be neglectful when reviewing the book. Don’t read beyond the fifth paragraph if you don’t want to know, although at some point when reading the book it will drop into place.

Singapore is held up to the outside world as a prosperous small state that’s a model of economic success, which is true, but most people outside the area are unaware of the cost in personal freedom, which Liew lays bare. Business and government connive together and the streets are free of chewing gum, but the same party has controlled the country since independence in 1965, and for the first forty years only two opposition MPs were elected. It’s detailed how one was constantly harassed via being dragged into court and fined.

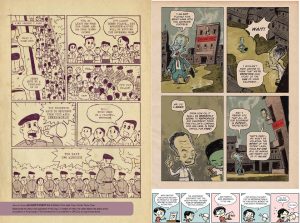

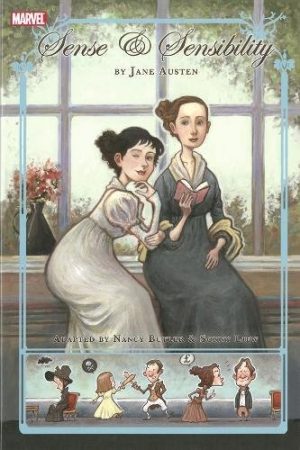

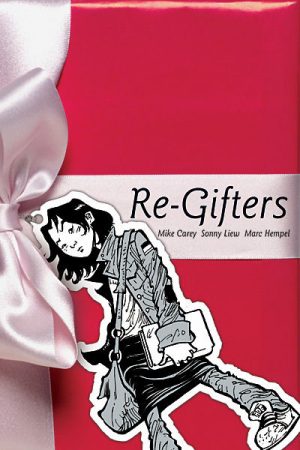

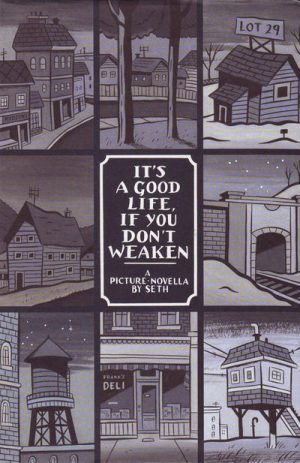

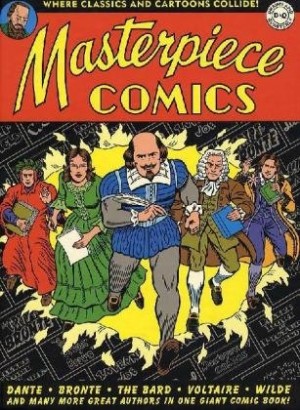

This, like other pivotal moments of Singapore’s history is seen via a succession of extremely well constructed pastiches of other comics through the ages by an extremely gifted artist. The styles of assorted artists are very recognisable, yet via their distinctive page designs rather than any outright swipes. Chye is shown influenced by likes of Osama Tezuka (sample art left), the Jack Davis Mad magazine parodies, or Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, and these scraps are punctuated by Liew’s tidy cartooning playing out the course of Chye’s life. The sheer variety of artistic approaches is remarkable, but their all being so accomplished is magnificent.

The torturous and devious methods used by the authorities in Singapore to maintain a singular version of truth while claiming to have a free press is exemplified by the short strip running along the bottom page of the sample art. Chye’s strips, though, from the 1950s to the 1980s constantly satirise the inconsistencies and twisted manipulation of local politics, with Walt Kelly’s form of political satire using funny animals in Pogo proving a reliable benchmark. The only real downside is a possible lack of appetite for reading about deceit and repression in Singapore.

So, to the big reveal. Chye’s career is presented in considerable detail, much effort expended by Liew on exploring the beginnings in the 1950s with reference to Harvey Kurtzman’s war comics and Eagle as well as Tezuka, showing Singapore as a cultural repository for international comics. What isn’t immediately apparent is that Charlie Chan Hock Chye is a fictional construct. The name may seem strange to older readers who’re aware of mystery novels of Earl Derr Biggers and the 1940s Charlie Chan detective films, but Liew plays it straight throughout only hinting at the fiction revealing truth.

The clever methods, political outrage and stunning art combine for a memorable achievement, and as a sideline Liew manages to stress the importance of artistic creativity even if labouring in anonymity. Magnificent.