Review by Frank Plowright

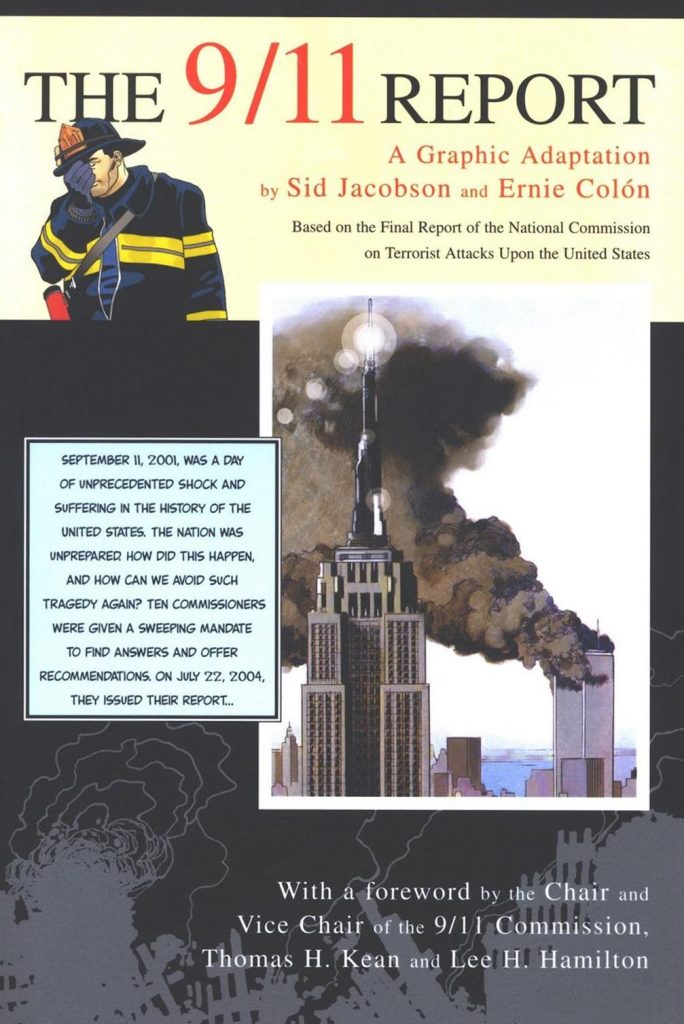

The attacks of September 11th 2001 will rank long in the memory of American history, and more than any other single cause have determined the path of the USA since then. In 2004 The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks on the USA published their final report. 28 pages believed to refer to specific foreign sources funding the terrorists remain classified, but 810 pages are downloadable in original form from the US government library site. Or just accept Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón have done their homework and yours, and consult their 131 page illustrated synopsis. The Committee’s Chair and Vice Chair both endorse the adaptation in their introduction.

Twelve themed chapters of varying lengths convey the essential information. If needed, validation of an illustrated version is supplied by an opening page where Colón provides portraits of the nineteen men responsible for flying the planes into the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon. They’re an ordinary looking bunch, some handsome, some more homely, but just seeing those faces will be a revelation for most people. Jacobson and Colón follow that with a timeline of what occurred on the flights and the dawning awareness of the US Air Traffic Control centres, and then of the President’s movements. The original report is forensically detailed as it’s a matter of public record, while Jacobson and Colón can reduce to essence, and this perhaps gives greater emphasis to a lack of communication between assorted departments.

A damning chapter reveals the evolution of US counter-terrorism, and its failings, although by the mid-1990s Bin Laden had been recognised as a global threat. Monitoring of him and his associates is likely to have prevented several disasters more than those definitively documented, but there was a reluctance to pursue a strike first policy. American global status seems to have instilled caution, the avoidance of possible civilian deaths in targeting Bin Laden prioritised.

Although adapting an official report may seem matter of fact, it’s apparent that nuance is very necessary and Colón’s years of storytelling experience is invaluable. Jacobson’s captions pack a lot of information, requiring Colón to illustrate plenty of meetings, conversations and briefings featuring locations and details. He achieves this in a manner that holds the interest as a succession of dry facts and everyday movements dominate. His likenesses of key personnel are good enough that there’s confidence he’s equally diligent for people not as well known, but when it comes to personalising those whose portraits he presented to begin the book he shows a different side to them. They’re now frowning, scowling and angry.

It’s possible to lose oneself in The 9/11 Report, the detail so fascinatingly forensic, the plotting so tight it can seem a novel. There’s no shortage of fictional tropes, such as the CIA and FBI both entrusted with a nation’s security, yet unwilling to trust each other, Bin Laden as a James Bond villain, and the tragedies of those trapped in the World Trade Center. The creators are condensing, but there’s still a considerable density.

This is a catalogue of appalling deeds darkly done, but includes little consideration of why the USA might generate such hate. The recommendations include treating people more humanely, abiding by rule of law and being generous, but in the fifteen years since publication there’s little evidence of that being the lesson learned. It’s a compelling read from which few emerge with credit.