Review by Ian Keogh

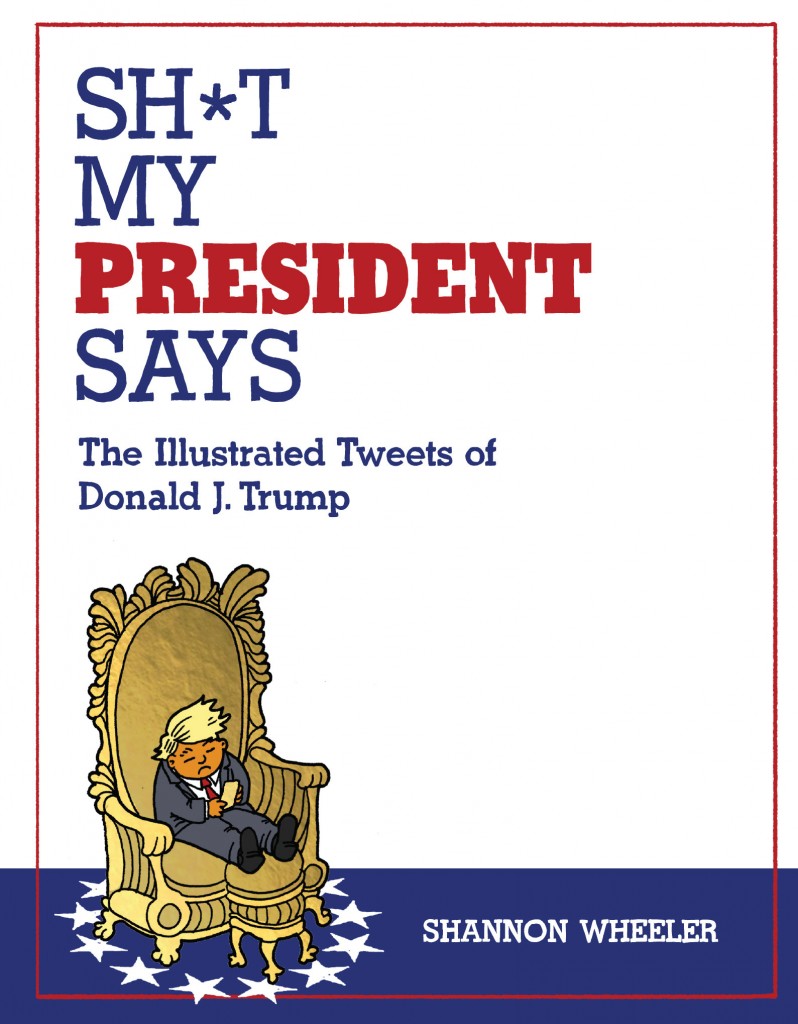

Character assassination is never more fun than when it’s someone performing the act on themselves, and no-one manages this more effortlessly than Donald Trump. He opened his Twitter account in 2009 to promote an appearance on the David Letterman Show, and since then has compiled tens of thousands of tweets. Shannon Wheeler has read them all, accusatory, aggressive, contradictory, gnomic, paranoid, promotional, and plain barking. Wheeler notes in his introduction that those he’s most interested in are those revealing the true man, or more accurately the child within, which is how Wheeler illustrates him.

With Trump’s tweets reported around the world on a daily basis his very individual brand of exhortation has a reach well beyond Twitter. Much of what Wheeler highlights pre-dates the presidency, but these have a fascinating insight. For a week in October 2012 Trump, multi-millionaire company CEO, had the time to exhort actor Robert Pattinson, presumably not a close friend, to dump his girlfriend Kristen Stewart after she’d had a fling with someone else. Six months after insultingly speculating as to her tendencies there’s a tweet wishing her a happy birthday.

The curious combination of monstrous ego and heightened sensitivity to comments from people he should care nothing about is frequent, and alongside this are comments reminding people of Trump’s supposed intelligence. That may be the case, yet he’s unable to resist any perceived upgrading of his own importance by association, nor is discretion a trait. A July 2103 tweet idly wondering if Vladimir Putin will become his new best friend may yet have future repercussions.

On so many occasions Wheeler highlights hypocrisy. A favourite faked disbelief of Trump’s is that while in office ex-President Obama would be playing golf while x or y occurred. Other recurring beliefs revealed are that money and intelligence should confer privilege. This is among tweets reinforcing a great capacity of self-delusion, one considering he won the popular vote in 2016 if votes cast by illegal immigrants are discounted. There’s also a monumentally ungracious marker for 9/11.

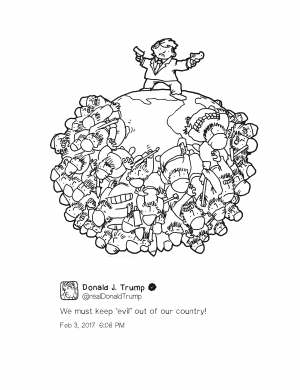

In compiling and contextualising the tweets via placement Wheeler’s work is first rate. It’s the tweets, however, that hold the fascination, and in order that it’s his book Wheeler has to contribute more, and that’s where Sh*t My President Says falls down. There’s nothing wrong with Wheeler’s illustrations per se. They’re amusing, charming and varied, but only very rarely do they illuminate the tweets to which they’re connected. Some explain, such as illos of prominent Muslim athletes accompanying a tweet denigrating them, and a rant against voters registered to vote in two states features those from Trump’s retinue entitled to do so. A continuing series of wall-building cartoons is funny, while there’s a great editorial style cartoon commenting on the complications of health care. These, however, are exceptions.

Does this invalidate Sh*t My President Says? Certainly not. Yet it’s depressing to consider that however misguided, misinformed, outrageous, and untrue much of the content is, Trump’s likely to exceed this on all counts.