Review by Ian Keogh

Philip Pullman’s Northern Lights trilogy is a fantasy set on an alternate Earth where many familiar touchstones are slightly twisted to provide a disorienting and imaginative experience. On this Earth the church wields greater influence, as do the pillars of the educational establishment, and some animals have achieved sentience.

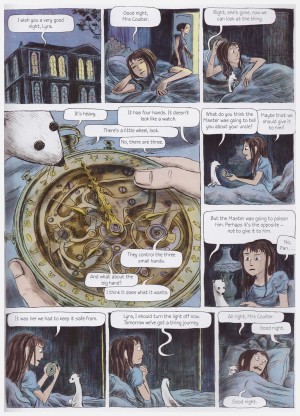

In his novel Pullman introduced many complex ideas about society and religion, and despite the protagonist being a child, it’s a work more adult in nature than the children’s books Pullman was previously known for. For instance, humans on this earth are bonded at birth to entities known as daemons, who are both lifelong protector and companion. During childhood their form shifts from one animal species to another, but settles as their charge becomes an adult.

The precocious Lyra Belacqua has grown up in the care of those running the colleges of Oxford University. She knows little of her background, which later becomes important, and while not bad-natured, a rebellious spirit of exploration leads to conflict with her guardians. She’s uncomfortable with the establishment formality of Oxford, and finds her friends outside that community. Against a background of children disappearing and possible political upheaval on a global scale, Lyra is informally adopted by the glamorous and influential Mrs Coulter, whom she is to accompany on an expedition. Before leaving Oxford, though, she’s presented with an alethiometer, a compass-like device that if interpreted correctly somehow tells the truth.

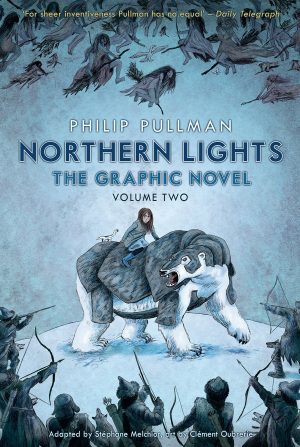

There’s a whole school of 21st century French cartooning that’s loose and individual without sacrificing any emotional resonance, and Clément Oubrerie falls squarely within. Best known previously for Aya of Yop City, he provides a deep visual characterisation over Pullman’s sprawling cast, simultaneously ensuring all major players are distinctive. His Lyra is suitably inquisitive, brave and resourceful, and Oubrerie’s daemons have a wonderful kinetic quality.

Stéphane Melchior’s adaptation is extremely good. There’s never a moment’s consideration that this graphic novel isn’t the source material, such is the attention to detail. Pullman’s complex ideas are slipped in sympathetically and concisely, and while there’s an inevitable loss in sacrificing Pullman’s rich language, Oubrerie’s contribution fills that gap. The bonus of simplifying and condensing the original is in rendering it accessible without difficulty to a far younger audience.

As frustrating as it may be when this adaptation doesn’t even cover the first half of the opening book in Pullman’s trilogy over sixty pages, it’s also satisfying that the approach is correct. The original work is a dense adventure, and splitting the adaptation into three parts permits the full atmosphere of Pullman’s imagination to seep through.

In the USA this is known as The Golden Compass Volume 1, instead using the title of Pullman’s second book in the trilogy. This book won the young readers prize at Angoulême, and the story continues in Volume Two.