Review by Graham Johnstone

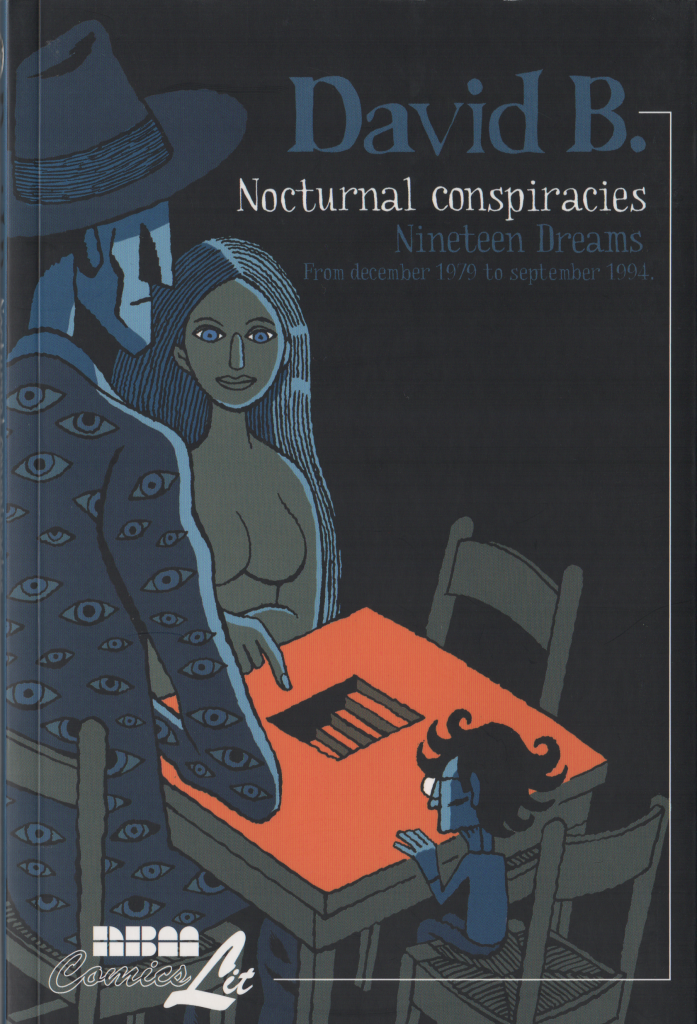

Between producing the six volumes collected in English as Epileptic, David B (aka Beauchard) recorded his dreams in comics form. His symbolic, expressive art was already dreamlike – so it makes perfect sense. The first batch, covering fifteen years, are collected in Nocturnal Conspiracies – Nineteen Dreams.

These dreams are vivid and dense. In the five page ‘Paris’ we see through the trees a Romanesque balustrade with classical statues. Suddenly we’re with a group of men shooting at a bus with an unseen foe aboard. Beams of light from its windows create white diagonals in the road. Then the front of the bus seems to turn in a giant armoured, or robot, face staring down its antagonists.

Dreams are generally stronger on themes than plot, and that’s true here – there’s no explaining of the events that led them here, only the relationships and feelings involved. The terse captions put us inside the dreams: “There’s something… that goes a whole lot deeper than just wanting to kill him”. In his brief foreword he describes these as “enigmas without solutions”, yet they generally have a sense of poetic completeness.

Real people feature in the dreams, and this supplies intriguing clues about Beauchard’s inspirations. In an early one, he’s standing on a balcony with fellow comics creators including George Pichard. You can see his influence in Beauchard’s loose, stylised figures, and flowing lines. In another, he is in a bookstore full of books by Polish born writer and artist Roland Topor, and again you see the influence on B of his surreal meditations upon identity and alienation. When he’s in the grounds of an art museum, ‘The Cat’ pursuing him, is (he tells us) from the sculpture of Giacometti, and you can see traces of his elongated, trembling, lines in Beauchard’s figures.

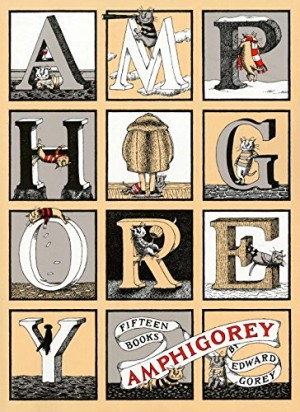

The art is of course excellent. If you know his work, it’s both just what you expect, and endlessly fresh. He uses his trademark heavy blacks, here enhanced by tones of blue and grey. The influence of Edward Gorey is evident, not just in the loose pen hatching, but also in the gothic atmosphere subtly leavened with ironic humour. For example, the whole page image in ‘Paris’ shows his mastery of design, rendering, and use of colour/tone. It’s mostly a panoramic view of the city – the landmark buildings rising up from the sea of rooftops, obsessively detailed with slates and chimneys. He conveys the man looking at this scene simply by his hand leaning on the balustrade, and the silhouette of a Giacometti style arm. It’s elegantly organised, with the cityscape shaded pale blue against the pure black and white foreground, and dark blue/grey sky.

The author, in his foreword, invites us to see this set of dreams as chapters in a novel. There’s no direct continuity, and no definite reappearances of characters or situations. However, there are recurring themes: being caught in events you don’t fully understand, and can’t control; people needing protection; cryptic codes and broken language… but are these specific to the author or simply typical of dreams?

There is though, a subtle progression from western settings, and scenarios of crime, to more international, political contexts – involving rebel forces, refugees, and so on. It’s tempting to see this as a manifestation of the shift in his focus over this fifteen year period, from personal and immediate family in Epileptic, to the broader scope of The Armed Garden and Best of Enemies.

It may not really be a novel, but it’s fascinating and powerful material told with poise and finesse, and dazzlingly visualised.