Review by Frank Plowright

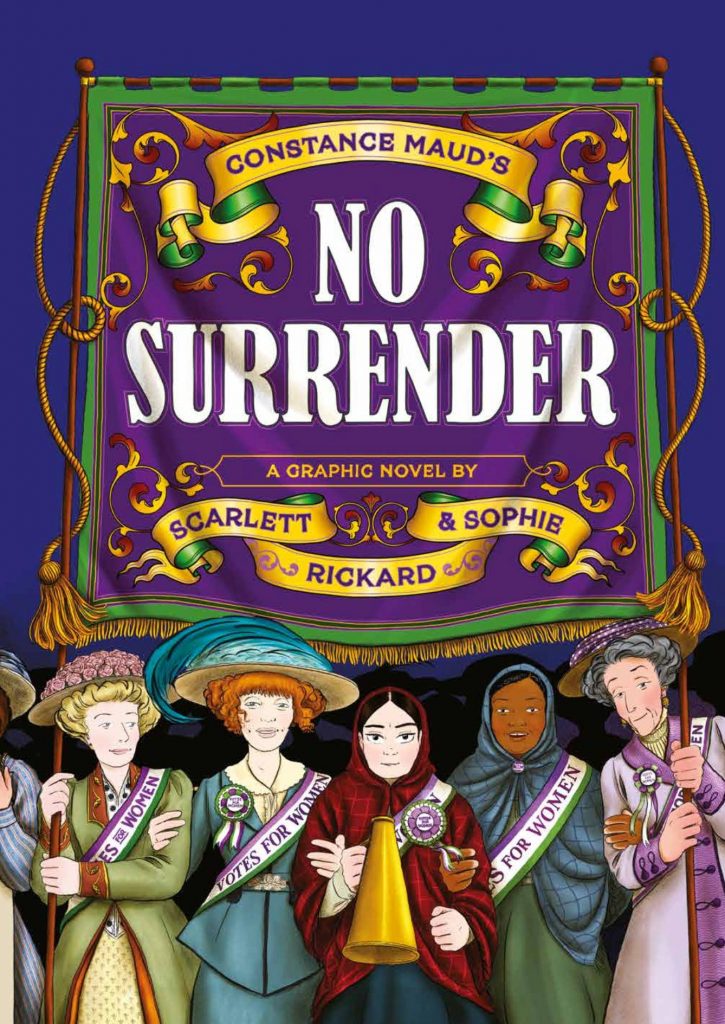

Constance Maud’s No Surrender was a battle cry when published in 1911, a time when the women’s suffrage movement was gathering momentum, yet many women remained unconvinced, never mind men. It took the path of most novels, falling out of print, and wasn’t reissued until the centenary of the original publication, which is presumably when Scarlett and Sophie Rickard first came across it.

It’s ostensibly the tale of Jenny Clegg, who’s been working at the textile mill since she was ten and has the strength to point out injustice as she sees it in her Northern English community where there’s barely a man who’s acceptable. The best of them is Jenny’s brother Peter, whose work-related injuries have left him without strength, but the remainder are wastrels, gamblers, wife-beaters, reactionary magistrates and bullies. Even the cast’s socialist agitator is firmly of the opinion women belong in the home, finding agreement with the upper classes. Most of the upper class women presented are equally caricatured, espousing that there must be a reason for restrictive laws or they wouldn’t have been passed, and in their ignorance founding anti-suffrage organisations.

In terms of spreading what was then a radical view, there are connections with another great activist novel of the early 20th century, The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists, not coincidentally the previous adaptation by Rickard sisters. It’s equally passionate in advocating a cause, but makes its points with greater subtlety. Perhaps a lack of subtlety was needed in 1911, but a century on a hectoring voice belabours the obvious, the melodrama overwhelms, and a diligently adapted 360 pages becomes a long read indeed.

It’s mitigated slightly by the precise period illustration providing the contrast between rich and poor, and showing in a far more nuanced way the need to redress the lack of equality. The cast visually reflect their personalities from resolute to cruel or weak, and great effort is put into busy panoramic scenes, especially at the end, with the care taken extending to decorative chapter separators.

When Maud wrote No Surrender the policeman for whom expediency ranks above truth and the prejudiced magistrate would have been eye-opening for some women readers, although they’d have been familiar with philanderers. Where the story is strongest, though, is toward the end with still shocking scenes of idealistic middle class Mary O’Neil in prison meeting others there and sticking to her principles. More powerful sequences like this and fewer lectures in the form of discussions would make Maud’s novel more readable today. The succession of conversions, both mentioned and seen over the final pages is almost laughable, and undermines the intention. On the one hand the Rickard sisters are stuck with the material they’re adapting and draw it very nicely, yet on the other it was their choice to adapt a novel important in its day, but poorly written.