Review by Frank Plowright

Nevsky is a strange beast, being a graphic novel adaptation of a film, one based on slim historical knowledge and filtered through a desire to reflect the ideology of the time and place it was made. This was in Soviet Russia in 1938.

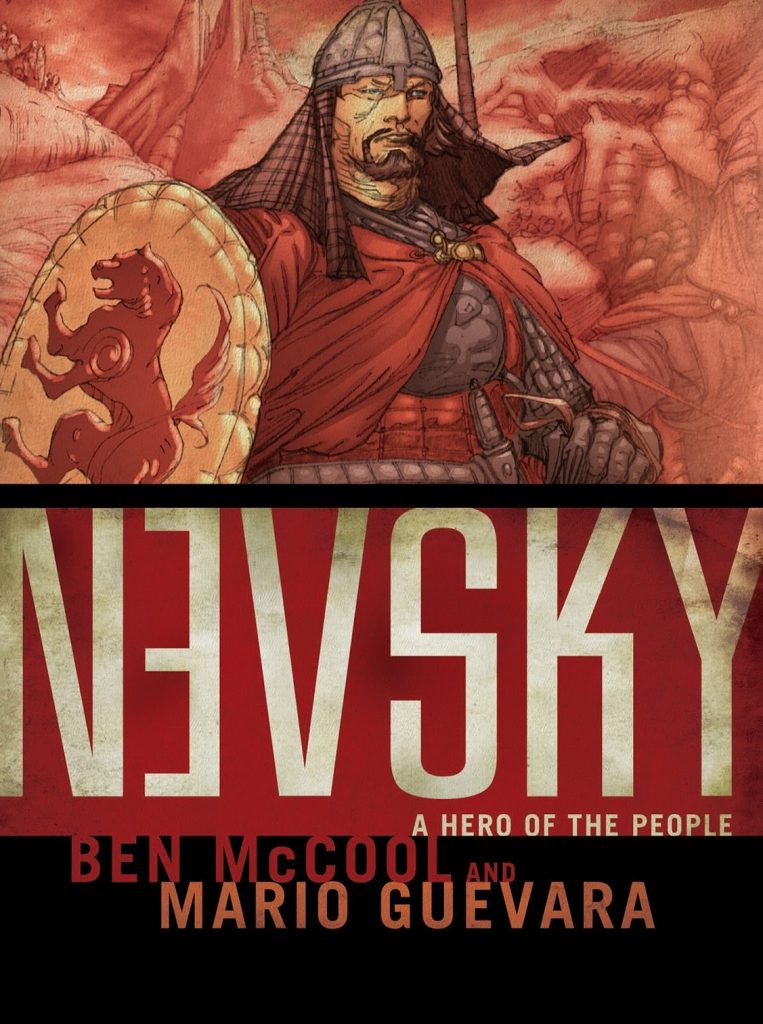

Sergei Eisenstein is best known for Battleship Potemkin, still ranked among the greatest movies of all time. His later career, however, was under the supervision of the Soviet authorities, and they assigned the task of producing a biography of Alexander Nevsky, considered a fitting hero for the era. It may seem a strange choice, because as a 13th century prince, Nevsky was certainly privileged, usually an insurmountable black mark in terms of Soviet ideology, but crucially he was one of the very few who successfully fended off both a Mongol invasion and one by German crusader knights. Robert Gotlieb’s introduction offers context to the classic film, before leaving us to Ben McCool and Mario Guevara’s adaptation.

Solid historical fact about Nevsky is still hard to come by, and in 1938 Eisenstein shaped his portrayal to the desires of the times. As a prominent Jew in Soviet Russia under Stalin he was always under threat, and if a few compromises with historical integrity kept him from a second spell in an asylum, Eisenstein surely took the pragmatic view.

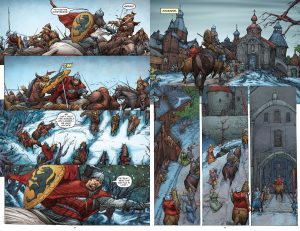

Many of the techniques Eisenstein evolved continue to influence films today, not least an acute awareness of cinema as spectacle, which could hang rather a millstone around the neck of any artist. Guevara, however, has the benefit of working in colour, and triumphs with pages offering that spectacle, rich in historical costumes and detailed battle scenes. His is a budget beyond Eisenstein. Nevsky’s first appearance is as the general leading Russian troops against the invading Mongols, separating their army and leading them into a trap where they’re slaughtered, and Guevara captures the rushing horses, the snowy forest and the ultimate cliffhanger. He employs a considered style suitable for the period, one that doesn’t glamorise the cast or their surroundings, where even what was considered opulent in the 13th century seems primitive today. He does follow the exaggeration of Eisenstein’s cast, frequent bold gestures being the order of the day.

It’s for his stand against the Mongols that Nevsky is remembered, and McCool adds a good opening sequence absent from the film commemorating this, before getting to the meat of the plot and the invasion of Pskov by the Teutonic Knights. The famous atrocities are conveyed, but with delicacy, and McCool doesn’t downplay the heroic Russian ideal at the heart of the film, his dialogue underlining the message meant to be spread.

To humanise the conflict there’s a subplot about two warriors each attempting to prove themselves worthy of a woman’s love, and while it comes to embody the film’s themes, it’s slow in taking off, and somewhat the distraction to begin with, but comes more to the fore in the final scenes. As in the film, the battle on the ice is an extended sequence in which Nevsky’s intuition and tactical mastery serve him well, and the heroism of Russia’s saviour is forged in glory.

It’s a stirring story, at least based on some truth, and while it’s faithful to Eisenstein’s film there are departures, biography favoured by adding the opening sequence, and Guevara having a more illustrative style. If anyone wants to make comparisons, the entire film (in Russian) is available on You Tube.