Review by Frank Plowright

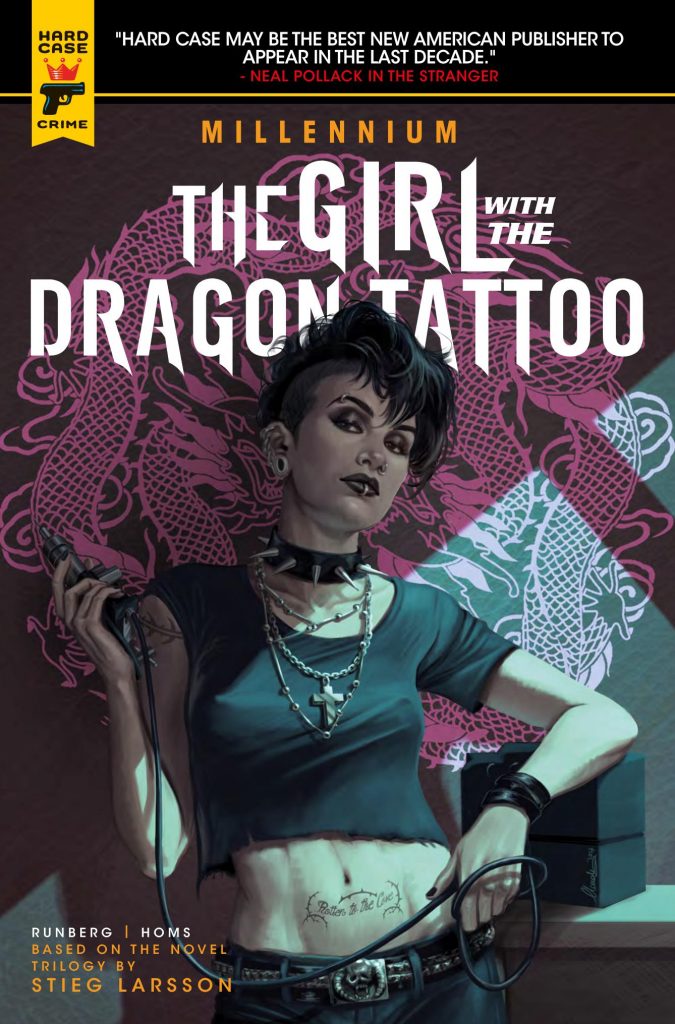

English language readers already have a graphic novel adaptation of Steig Larsson’s global best selling novel available to them from Vertigo. However, this translated European version may have been published later and have fewer pages, but it’s far pacier and an altogether better read.

There are several reasons. Most obviously, there’s the benefit of having a single artist illustrate the entire adaptation, rather than Vertigo’s strange method of using two, with contrasting styles alternating according to which of the main characters was being used. Furthermore Sylvain Runberg has been far more ruthless in chopping out scenes from the original novel that would slow the pace down, and aren’t very relevant to the ongoing plot. There’s a case to be made that he’s actually improved on Larsson’s work by doing this.

Mikael Blomqvist is a middle aged journalist with a formidable reputation, but the book opens with him at his lowest ebb, just having been successfully sued for libel, throwing both his reputation and that of the magazine he co-founded into doubt. This doesn’t bother newspaper proprietor Henrik Vanger, who appoints Blomqvist to investigate the disappearance of his niece decades previously. He has good reason to believe she’s still alive, and will provide the evidence that Blomqvist lacked in his trial. Vanger believes one of his relatives responsible, and Blomqvist’s excuse for circulating among the dysfunctional family is that he’ll be writing the family history. The girl with the dragon tattoo is Lisbeth Salander, a young woman with psychiatric problems, but a superb investigator, and a woman well able to take care of herself. What’s downplayed here compared with the Vertigo adaptation are the suggestions of Lisbeth being on the autistic scale.

Most of the plot problems stem from Larsson’s original novel. Blomqvist is generally well conceived, but his unconvincing allure to any woman he comes across is straight from 1950s crime fiction, and a clue involving a sequence of numbers that’s baffled investigators for years is disclosed as something any half-decent detective would have considered. To be fair to Larsson’s there’s an awful lot of good also, particularly where the plot winds when it seems the main case has been solved, and Lisbeth’s surly, no nonsense personality, along with her methods of dealing with people.

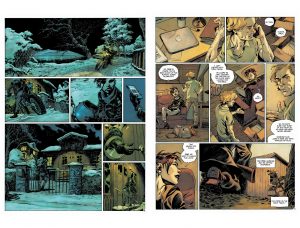

José Homs is a superb artist working in the broad cartoon naturalism common in Europe. His character designs avoid the stock attractive people usually found in comics, so making them more believable, and that carries over to his environments. Whether a scene is set outside the court house, inside a home for an evening meal or in the cellar of a sadistic murderer, Homs renders it fully, including the little details that convince that the locations are occupied.

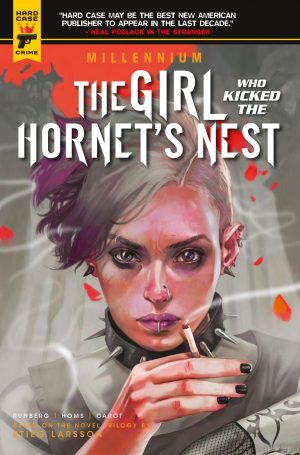

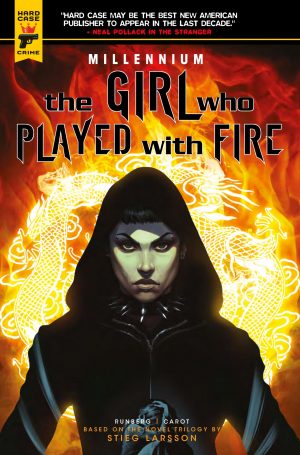

Despite having connections, it’s not until the halfway point that the two main characters meet, and from that point the plot accelerates, and it’s with this section that Larsson’s devious plotting comes into its own, with Runeberg just giving it a nudge here or there. The result is a pacy crime drama that’s almost an object lesson in how to adapt for a different medium. This is just the opening chapter of a trilogy, and the cast return in The Girl Who Played With Fire.