Review by Cefn Ridout

In 1987, on the publication of the German edition of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, a reporter asked the author whether he thought a “comic book about the Holocaust was in bad taste”. The retort was classic Spiegelman: “No, I thought Aushwitz was in bad taste.” It reveals much about the man and his work – acerbic, uncompromising and prepared to challenge lazy misconceptions about his chosen subject and medium of expression.

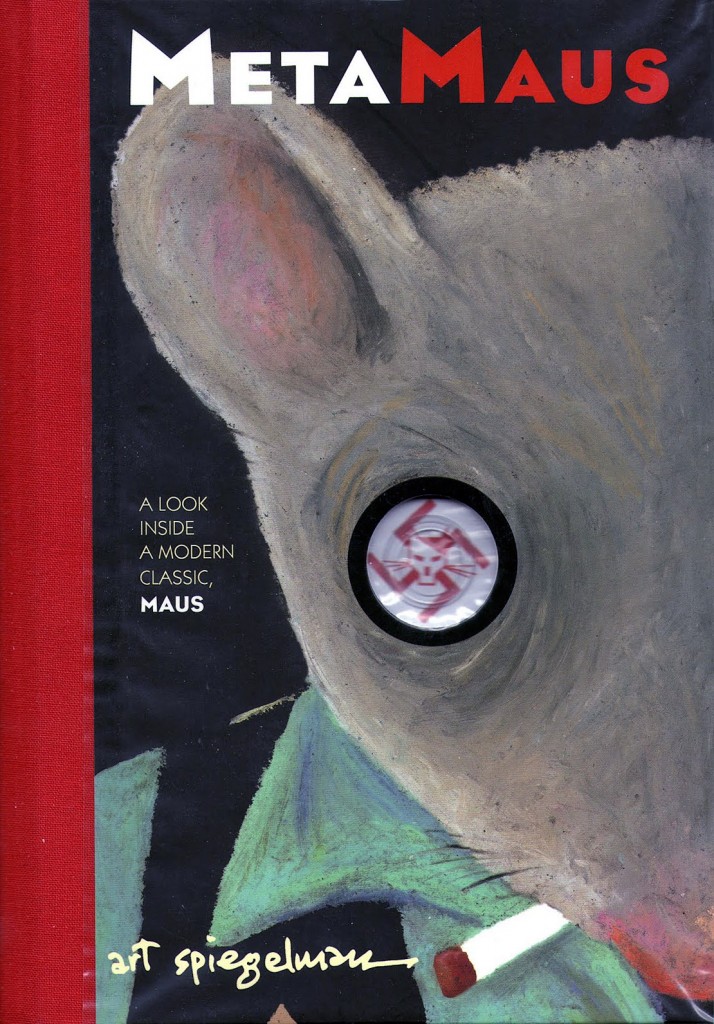

The anecdote is one of several acute observations found in MetaMaus, an exhaustive, multifaceted account of the creation and reception of Spiegelman’s graphic memoir. That Maus went on to pick up a Pulitzer prize, confirming the comic medium’s capacity to deal with serious themes, attests to the author’s considerable skills, sensibility and chutzpah.

Given Maus’s own richly layered recapitulation of personal and collective history, and insights into Spiegelman’s creative process, do we need a companion ‘making of’ volume? Surprisingly, yes. In other hands, this could have been embarrassing indulgence. Instead, it’s an embarrassment of riches.

Built around academic Hilary Chute’s engaging, if overly deferential, interview with Spiegelman, MetaMaus and its accompanying DVD compile sketches, essays, drafts, photos, post-war pamphlets and video clips, alongside a digital version of The Complete Maus with commentary, perceptive family discussions, amusing rejection letters from short-sighted publishers and the audio and unedited transcripts of Spiegelman’s conversations with his father Vladek – the foundations of Maus. And throughout, the author’s incisive, prickly intelligence, self-critical candour and ethical rigour are on full display.

Spiegelman asserts that Maus is “about the Holocaust and its impact on the survivors and those who survive the survivors”. Yet Maus also examines “the retrieval (and) creation of memory”, and its inherently elusive nature. The author strives for a deeper understanding of his ‘troubled’ relationship with his father by retelling and reimagining what his parents lived through in the concentration camps, and by placing himself firmly in the frame. The resulting tension gives the book its enduring, emotional resonance.

Representing his characters as animals was a conceit Spiegelman had trialled earlier. In his contribution to Robert Crumb’s 1971 underground anthology Funny Animals, he turned the Nazi’s dehumanising caricatures of Jews as rats and vermin against themselves. The animal masks allowed him to “approach unsayable things”, but upon expanding his bestiary in Maus to include pigs as Poles, dogs as Americans, fish as Brits, and even reindeers as Swedes, he admits to struggling with his metaphors.

An erudite, spiky advocate for the medium, Spiegelman is at his riveting best expounding on the unique qualities of comic storytelling and his own tortuous methodology.

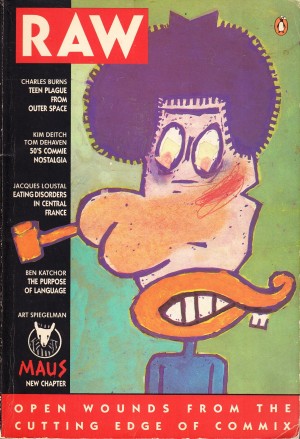

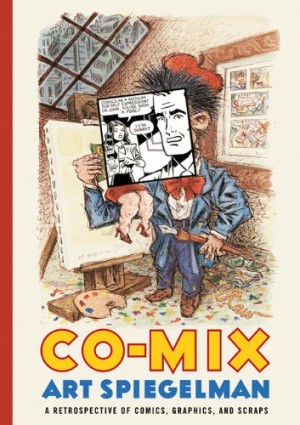

Looking at his own evolution as an artist, he draws a compelling line from expressionist satirists like Otto Dix and George Grosz, through the revelatory influence of Harvey Kurtzman’s pioneering Mad magazine, to his own work in underground comix and co-creating, with his wife, Francoise Mouly, the groundbreaking comic arts magazine Raw, wherein Maus was first serialised.

A 13-year labour of love, Maus allowed Spiegelman to hone his craft and distil the essence of the story, and to also rein in his natural inclination to experiment with the form – almost. He embedded his formalist tendencies in the book’s outwardly conventional narrative: employing almost subliminal symbolism; mapping the human geography of the death camps; and developing different beats for three separate periods.

MetaMaus could be sub-titled “All you wanted to know about Maus, but were afraid to ask”. Even fans of his work may be overwhelmed by the sheer wealth of material on offer. Yet there are few graphic novels that deserve this level of analysis, and Maus would be at the top of that shortlist.