Review by Frank Plowright

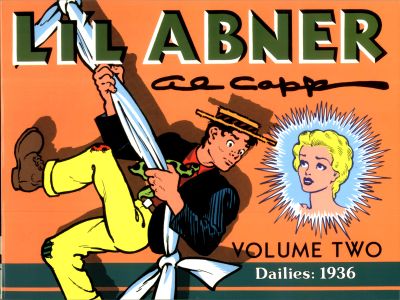

With Volume Two Kitchen Sink’s Li’l Abner reprints settle down into slightly slimmer packages covering a year of the original continuity. Al Capp would customarily end one of his serialised stories around the festive season, and it makes for a convenient breaking point.

Volume One presented a strip with the strong foundation of a knockabout hillbilly community not entirely sure of where to head. Capp decided early that the ignorance of the good-hearted Li’l Abner in New York was where the comedy lay, not realising it was rather the dead end, and Dogpatch provided the real spectacle. It also supplied unique and engaging characters rather than types common to other newspaper strips of the 1930s. There’s more time spent there in this collection.

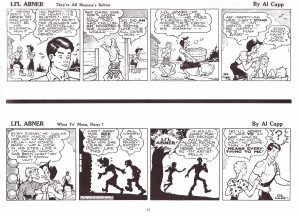

Capp’s quoted in the introductory material as considering that suspense was the most important factor in sustaining Li’l Abner. A collection where the following strip is instantly available can’t adequately convey his skilled arrangements when people had to wait 24 hours for the continuation in the next day’s newspaper. Indeed, it diminishes the technique by revealing how he repeats devices and get-outs, although he’s imaginative when it comes to prolonging the tension over a long period. Some sequences, though, transcend the repetition, still generating tension, such as the fate of Abner stuck in a cave.

By any standards the opening continuity isn’t the strip’s finest hour, featuring ignorant comments from Pappy Yokum wandering into New York’s Chinese community, and Capp expecting the audience to believe he’d be mistaken for an FBI agent. Thankfully, it doesn’t last long before we’re into one of Li’l Abner’s much loved recurring sequences, Abner not willing to commit to Daisy Mae, but jealous of someone else seeing her. This is a few weeks after another regular scare of Abner almost married. Capp becomes ever more ingenious in manipulating this situation over time, with greater extended sequences, but for now it remains brief. Capp instead falls back on knockabout comedy, with lookalikes (used twice), gangster slang taken literally or the inspiration for long sequences originating from cinema horror and college movies. It’s nowhere near the later satirical wit Capp would apply, but there’s a definite poking at film clichés. At the same time more original touches are gradually incorporated. Mammy’s visions first appeared in Volume One, and they’re a neat means of achieving the impossible, and extended sequences focus on either her solo, or with Pappy, Abner unseen for two months between June and August 1936.

Capp’s art is also coming along a treat. It’s nowhere near peak period, but the characters sparkle and if the panels are sometimes awkwardly composed, there are others where a crowd is effortlessly accommodated. The charming silhouette panels are more ambitious, and the little visual asides raise a smile.

For all that, Capp’s still building the formula for success, and while a slight improvement on the first outing, Volume Two still isn’t the selection to start with. An innovative tradition, though, is introduced in Volume Three.