Review by Frank Plowright

There are now differences of opinion among psychoanalytic practitioners regarding how much Sigmund Freud was right about. Some of his attitudes, especially toward women, make little sense. However, where there should be no disagreement is that his theorising and research represented massive breakthroughs at the time, and are the building blocks on which modern psychoanalysis is based.

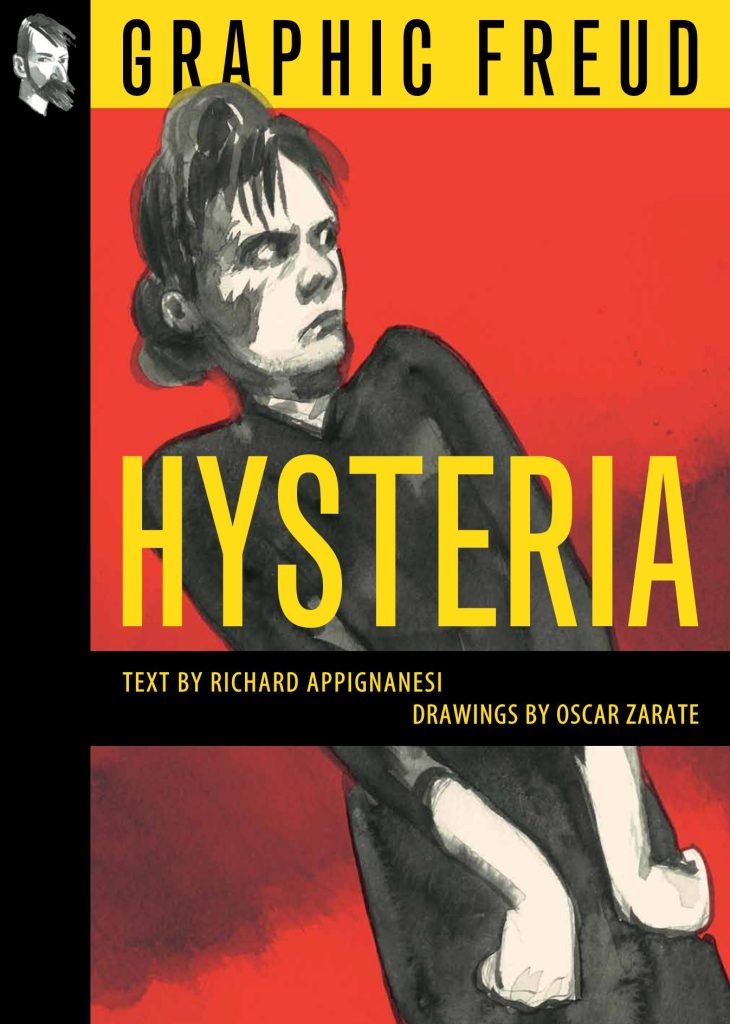

The Wolf Man was the first in a series of graphic novels presenting some of Freud’s analytical studies, and this is the second. The title is offensive today, but was applied to a broad range of problems women experienced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In hindsight the symptoms are hardly surprising given the widespread male attitude to women as inferior beings, decorative at best, but unequal and suppressed.

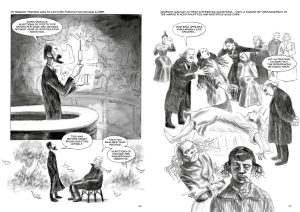

Richard Appignanesi doesn’t begin with case studies, but he contextualises them by starting with the elderly Freud reflecting on occurrences from his past, largely disappointments, both in studies and humanity, and offering his own commentary in hindsight. It’s dense and compelling, drawn with a lively intuition by Oscar Zarate, who brings complexity to life with compactly selected panel compositions packed with people, each of them distinct, and also applies an imaginative illustrative curtain over distressing scenes. It’s the imaginative art the previous volume lacked. Zarate’s versatility also includes a wry visual sense of humour. This is most apparent during sequences of the wild and dangerous experimentation undertaken by Freud and contemporaries.

Some of these are comic, some jaw-dropping, but ultimately there’s a horrific progression as Freud studies under neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. Abuse is a common thread between all the women Freud discusses, and that continues as those working for Charcot commonly rape the women in his asylum. Charcot’s theories are appallingly misguided, seemingly plucked from the air in the hopes of curing assorted symptoms considered to be hysteria, yet in his time he was considered a leader in his field.

Once Freud follows up on attempting to define a cause for hysteria, Appignanesi’s narrative switches to case studies. The ghost of Charcot hovers over Freud’s own interpretations as he probes ever deeper into the pasts of women afflicted with physical symptoms that medical doctors can find no cause for. Appignanesi’s Freud isn’t the man of certainty he’s often assumed to be, and we’re shown that he struggles with reasoning, and is far more methodical in discovering answers than Charcot’s habit of fitting symptoms to theories. In Hysteria his older self is eventually there to classify errors.

Rather than ending on a triumph there’s a clever finale using Princess Diana to underline that mentally induced physical symptoms still manifest in people even if the term “hysteria” is no longer applied. Appignanesi and Zarate manage to distil complexity into clarity with wit and style, acknowledging the mistakes of the past as stepping stones in what’s a fascinating read for anyone with an interest in Freud or his subject matter. Frink and Freud is the next in the series.