Review by Ian Keogh

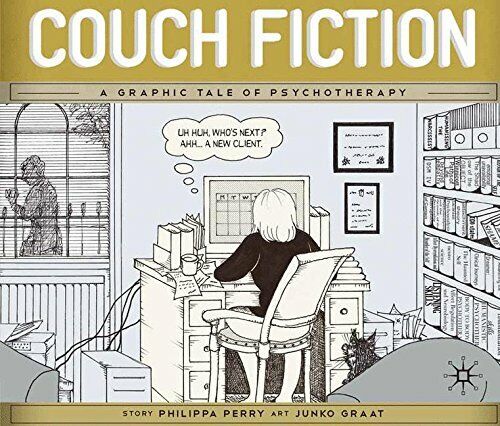

Couch Fiction follows a new arrival through the process of psychotherapy, attempting to analyse the root of their problem, and takes an interesting approach to comics by having the associated thoughts of author Philippa Perry at the bottom of each page supplied as text. These can be as focussed as noting the techniques of the psychotherapist or as random as wondering about the contents of recycling bins on their doorstep. It’s like the radio cricket commentator sometimes having action to consider, and at other times having to fill space. As Perry says in her introduction, though, these can be ignored, although anyone who does so will miss half the experience.

Pat is the psychotherapist followed as she takes on new client James. Psychotherapy is founded on honesty, but as the word “fiction” is there in the title, readers may at first wonder how much truth James is telling. He says he’s a successful barrister, and despite his voluntarily attending therapy sessions he’s barely forthcoming as Pat tries to coax him out. The unusual aspect is that along with the talk Perry reveals Pat and James’ thoughts, adding an extra level of uncertainty to an already fraught process, and it’s completely captivating.

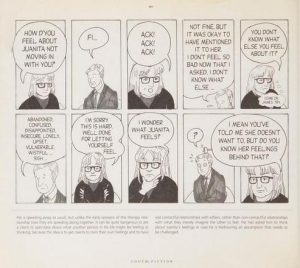

Artist Junko Graat’s name only comes up online in connection with Couch Fiction, and the end of book information credits a Japanese product designer who came to the UK to study horticulture and now works as a gardener. Hmmm. To begin with she largely sticks to just the single panel on each page, most frequently a plain picture of conversation in the surroundings of Pat’s office, but the artistic horizons are then broadened to encompass more traditional strip work. It’s never eye-catching, but it’s not meant to be, and the flatness perhaps conveys part of the process.

Perry is a psychotherapist herself, and given that Pat is drawn as a middle-aged woman with glasses the feeling of an avatar is hard to escape. The process is followed from start to completion, and laying it bare might surprise sceptics. One item that may disturb is how it’s taken for granted the subject can form an attachment to their therapist. It’s also clear that breaking down mental barriers to get at the truth of why someone behaves in a certain way isn’t going to be achieved in a single £60 session. The process is gradual, requires honesty inside and outside the consultation, and follows stages a psychotherapist can predict. In James’ case 43 sessions are noted. Just as well he really is a barrister.

Thought balloons have become a derided shorthand in modern comics, now largely replaced by first person captions, yet they’re integral to Couch Fiction. A door is opened into a previously undisclosed world for people who’ve never undertaken therapy, and those who have will achieve new insight via the revelations as to what Pat is thinking as she consults with a client. Perry’s notes beneath increase the understanding. The result is innovative use of comic form as an educational tool.

In 2020 Perry reissued Couch Fiction completely redrawn by her daughter Flo Perry.