Review by Graham Johnstone

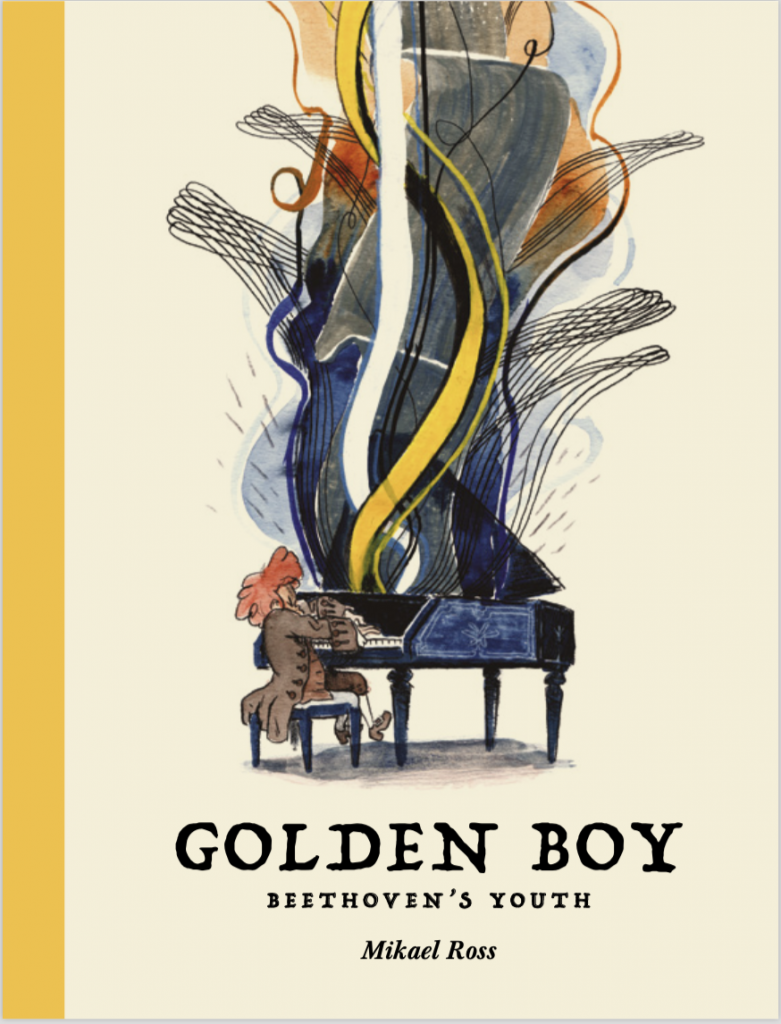

Mikaël Ross’ previous book The Thud involved a young boy forced to negotiate the adult world. Golden Boy, explores a similar theme, but this time focusses on child prodigy Ludwig van Beethoven.

Ross hooks the reader with a strong opening sequence. Young Ludwig is philosophising and trying to command the elements as if he were conducting music. However, he’s interrupted by a pratfall, and his brothers’ scatological jokes. It’s a fine summation of the tensions between the protagonist’s lofty ambitions and humble reality, and an indication of Ross’ irreverent treatment of the enduringly fêted composer.

Beethoven admirers may associate the low humour with comics. However, the approach channels period literary styles – the ‘picaresque’ adventures of a low-class rogue, the earthy humour of burlesque, and a strand of toilet humour going back at least to the ancient Greeks. Ludwig’s role-model Mozart also incorporated scatological elements into his work, so theres a sound, historical basis for its use here.

Behind the humour, there’s a full and frank account of Beethoven’s formative years. For the earliest period in Bonn, that includes his pushy, money-grubbing father, creditors, supporters, and teachers, as well as aspiring singer and love-interest Magdalena Willman. As a young man in Vienna, Ludwig rediscovers the now successful Magdalena, and his composer heroes Haydn and Mozart. Comic encounters bring the large cast to life, while progressing the story, and incrementally revealing Ludwig.

It starts in 1778, with Ludwig’s father marketing him as a child prodigy. If this recalls the story of Mozart (already the subject of two graphic novels), that’s accurate, with historians suggesting Beethoven senior was trying to ‘do a Mozart’. As with the earlier prodigy, talent is no guarantee of a gainful career as on top of the debt-ridden family’s struggles to fund him, there’s a smallpox epidemic. Elements like Ludwig’s terror of performance and his body’s violent reactions, may be exaggerated, but are plausible, and add welcome tension to what we know is inevitably a success story.

Irreverence disguises skilled storytelling. Ross avoids narrative captions, instead weaving explanatory details into dramatised scenes and sharp dialogue. When the story jumps several years, an update is woven into a comic dialogue with Ludwig shouting up to Magdalena’s window. His longed for introduction to Mozart is provided by a ‘poop princess’ as they squat over adjacent buckets at her makeshift public convenience. It’s a clever reversal of the sickly Rom Com ‘meet cute’. Ludwig’s musical development is covered too, as we see him learning to hear, imagine, recreate, and combine sounds (featured image, right). The period backdrop is also well evoked, comedically with the quack remedies applied to the ever sickly prodigy, and dramatically, with the Revolutionary Wars threatening Vienna and keeping Ludwig apart from his family.

Ross applies an expressive, cartoon style (think Calvin and Hobbes), that well suits this childhood world of frenzied action and slapstick violence. Ludwig’s huge cartoon eyes and diminutive size suggest an eternal child. This jars when he’s making advances to visually adult women, but by the end of the book, his face records experience far beyond his twenty-one years. Compared to a more modern style on The Thud, Ross here evokes period illustration and cartooning. His rendering looks deliberately rough (perhaps scanned from the pencils), with Claire Paq’s muted colours further evoking some crumbling historic tome. The settings conjure the era’s wealth or (more usually) squalor. Best of all are his vivid depictions of Ludwig’s extremes, when he’s delirious with fever or in the heat of composing (both pictured).

Whether playing comedy, drama, history or biography, Golden Boy hits all the right notes..