Review by Frank Plowright

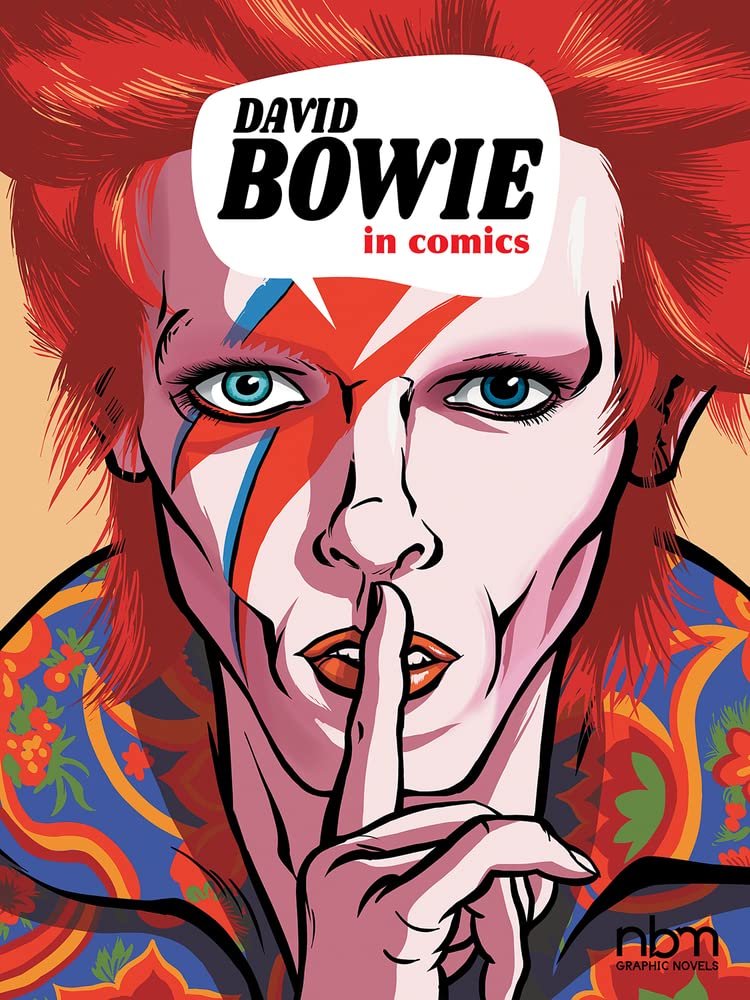

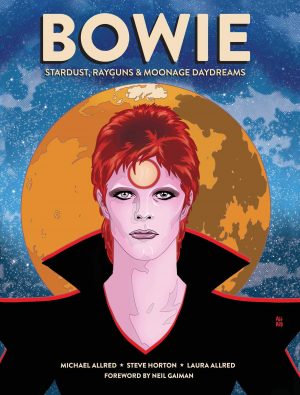

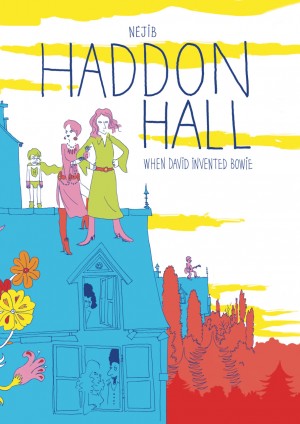

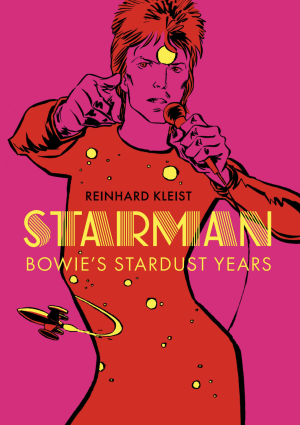

The shorthand career appreciation of David Bowie concerns his constantly adopting and shedding musical and stylistic influences, with the term “chameleon” frequently applied. It makes him, then, more suited than earlier musicians in this series to a biography told using multiple artists to illustrate chapters of a life.

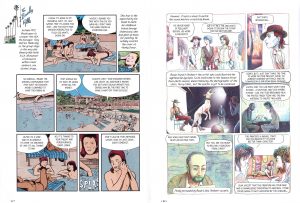

Compared with the previous books (The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Marley, Michael Jackson), there are fewer artists contributing, most taking on two chapters. Their styles are almost all within the broad form of cartooning, on the scale from Martin Trystram’s sweet comedy stylings applied to the child Bowie through the static, brightly coloured realism of Monsieur Iou, to the awkward digital realism of Samuel Figuière. There is no favouritism given Bowie’s long influence, but Christopher (sample left) picks up both the Ziggy Stardust and Berlin chapters. The other sample art is Léonie Bischoff’s interesting avoidance of black. The work of all illustrators is seen opposite the credits page on a nice montage featuring Bowie’s portrait at various stages of his life.

Thierry Lamy breaks down the key Bowie moments, both pre and post fame, covering Bowie’s entire life, and explaining him well in terms of music, drive and observation. He’s particularly good at pointing out the lasting influence of step-brother Terry, how Bowie works other influences into something different, and the relentless search for the new. He also includes interesting moments away from the limelight, such as Bowie’s childhood saxophone teacher Ronnie Ross playing for Lou Reed. Contextualising essays by Nicolas Finet provide more information, accompanied by photographs of Bowie and memorabilia. This is handled more sympathetically than in some earlier books, complementing the strips rather than rephrasing the same information. However, Lamy largely opts for dialogue over explanatory captions, and that dialogue is relentlessly banal. Time and again reading grinds to a halt for a really poorly considered speech, and the pages where Lamy uses captions are a relief. This isn’t just down to translation from the French edition, although Finet’s essays could have been more sympathetically written in English. Fans will further be irritated by sloppy mistakes such as “Lou Rood”, “TPOP” as an acronym for Top of the Pops, “Tin Machin” and the drug “heroine”.

However, as with so much about Bowie, fascination should transcend the mis-steps, and Lamy’s own creativity enlivens a speculative final chapter summarising the musical aspects of Bowie’s path through life. He’s already given due recognition to the acting. Some artists are slightly weaker than others, but no-one stands out as poor, and the best of them bring something individual to their interpretation of Bowie.

So, not the perfection some might hope for, but a solid run through of Bowie’s continuing importance.