Review by Frank Plowright

There aren’t many creators both writing and drawing their material who can seriously claim to challenge Posy Simmonds as Britain’s top graphic novelist. Her case is made via a meticulously composed backlist dating from the 1980s, a claim to have produced the UK’s first graphic novel with True Love, and, first and foremost, by the sheer magnificent observational quality of her work. Her speciality has been highlighting pomposity, philandering and hypocrisy among Britain’s middle classes, who graciously provide a near endless source of inspiration, but no-one else has managed this with what seems such effortless grace. Her people are joyously expressive and her insights capture a feeling so succinctly. Simmonds is serenely effective at slice of life drama, whether over single page newspaper strips or fully realised graphic novels, so it’s a real surprise that as much as anything Cassandra Darke is a crime story. A very British one that plays to her strengths, but a crime story nonetheless, and having decided to focus on crime, Simmonds packs her story with a comprehensive variety of assaults on the law.

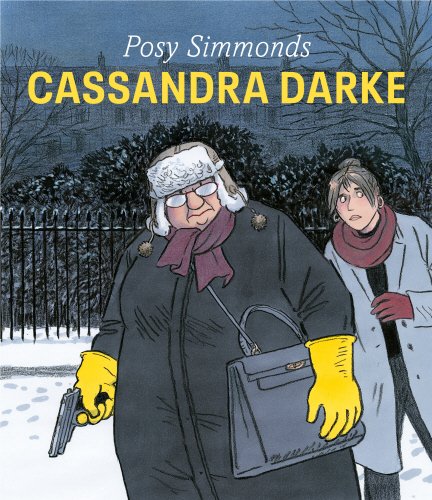

Cassandra herself is a disgraced art dealer, convicted for the fraudulent selling of copies, yet contrite only at being caught and the damage to her lifestyle. She’s a magnificently festering creation, entitled, judgemental and captured in all her middle-aged misanthropic glory on the cover, her headwear very much resembling book cover illustrations of another great misanthrope, Ignatius J. Reilly from A Confederacy of Dunces. Although it takes some admitting, Cassandra has lost her way. She’s confidently forthright without ever considering a person may need to develop as an artist does, to make the mistakes resulting in a fully rounded character. The primary source of Cassandra’s superiority complex is her step-niece Nicki, who sets the plot in motion, by moving into the basement flat at Cassandra’s property, and becoming involved with Billy, a good natured and protective guy who’s done something stupid. Dangerous people are looking for him, and they’d already assaulted Nicki before she met Billy.

Once read, and the pages turn rapidly, there’s the time to admire how Simmonds does so much so well. Cassandra Darke employs her usual method of combining text and illustration with comic strip, and we’re provided with some stunningly composed single images. The nuanced visual characterisation is graceful, and the phenomenal eye for behavioural detail is still present, with delightful scenes of the obese Cassandra squashing herself into people on public transport, unconcerned with their condemnatory stares. Other lovely storytelling touches are pages with Cassandra’s venomous and presumptuous comments about Nicki followed by a page revealing the truth, and the precise confluence of two stories on a single night.

Late on her career Simmonds has tapped into quite the sentimental streak. There’s little overt sentimentality, but Cassandra Darke is a work of redemption. In the past Simmonds has updated literary classics, and while there’s nothing as obvious as three ghosts, A Christmas Carol must have been an influence, in setting, social commentary and general tone. Yet Simmonds isn’t an ageing creator afraid of technology, as texting, pop-up urban art and the burlesque revival are smoothly incorporated, as is the horror of sexual trafficking.

It might be expected that a back cover blurb claims this is Simmonds’ best book yet, but there’s truth in that. At the height of her career and acclaim she’s stretched herself and applied her finely honed technique to something different while maintaining her dramatic and cultural mastery. Another gem.