Review by Graham Johnstone

Beyond the Pale is a collection, of early short pieces by Kim Dietch, published in a various US underground ‘comix’ between 1969 and 1984. Deitch would become an elder statesman of alternative comics, and a precursor to now long established creators like Charles Burns, and this volume shows his journey from relative beginner to mature writer and artist.

His introduction tells us his first work was published in New York’s counter-cultural East Village Other, but only after he responded to their request to “get psychedelic”. You can see that in 1969’s ‘Cryin’ (Ain’t Lyin’)’. Deitch himself was much less concerned with the standard counter-cultural subject matter of sex, protest politics, and drug culture. That said, he does have a fascination with the mystical and supernatural, although he approaches it from a distanced, skeptical perspective, and his intricate page layouts do chime with psychedelia. His mature work actually post-dates the underground comix boom years of 1969 to 1974 and he arguably began his best and most productive period some thirty years after starting.

‘Born Again’ from 1972 is typical of his style at that time. Figures are naturalistic but simplified, and rendered in heavy brush outlines, generally without modelling or shading. Faces have slightly exaggerated features and expressions, and it’s overlaid with zipatone style mechanical grey tones. In the story we see emerging Deitch elements: an institutional setting, a dissolute rogue, and a guru figure claiming mystic powers. Sauve Cosmo La Vey convinces his death row neighbour Silk Miller that with a published technique they can both cheat death and become famous. It works well for Cosmo, and with an unwelcome twist for Silk. With typical Deitch irony it ends with a note that says “This is a true story, and only the names and vegetables have been changed”.

The longest story here is ‘Miles Microft’s Last Case’ originally published as Deitch’s own 1973 pamphlet Corn Fed Comics #2. The style is slightly nearer his mature work, it still has the heavy, inelegant, outlines, but with feathered shading instead of zipatone. All the elements of his style are now in place and he gradually refines them over these thirty pages. Microft, self-styled Psychic Detective, would be a recurring character, and again the story has classic Deitch elements of tongue-in-cheek sci-fi and time travel. New to the longer page-count though, the plot is perhaps too intricate.

In the stories from 1975 and after, we see Deitch as a master of composition to rival Jack Kirby and Hergé. He conveys elaborate spaces filled with living, breathing characters, and fantastically realised props and settings. Deitch arguably set himself a harder task to give coherence without colour, instead creating nuanced grey tones with his now trademark feathered brush lines. It requires close inspection to determine these have indeed been created by hand and brush.

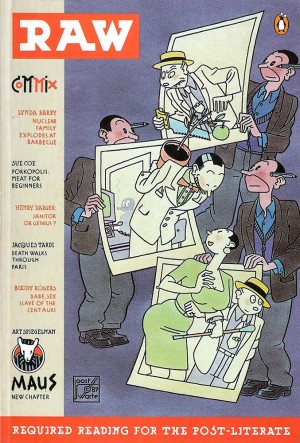

Best of all are the five pieces from Arcade – Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith’s mid-1970s ‘life-raft’ for the best talents from the rapidly collapsing underground comix. In ‘Possessed’ we revisit Miles Microft – now resident in Berndale Acres, where the troubled Ted and Nate Miskin from Boulevard of Broken Dreams will later be ‘guests’. The two ‘Famous Fraud’ pieces explore the “old, weird America” (as a publisher’s blurb put it) that would be the focus of his later work, particularly Shadowland.

The best pieces here are among the very best American alternative comix (or indeed comics) of the 1970s, and still stunning today.