Review by Frank Plowright

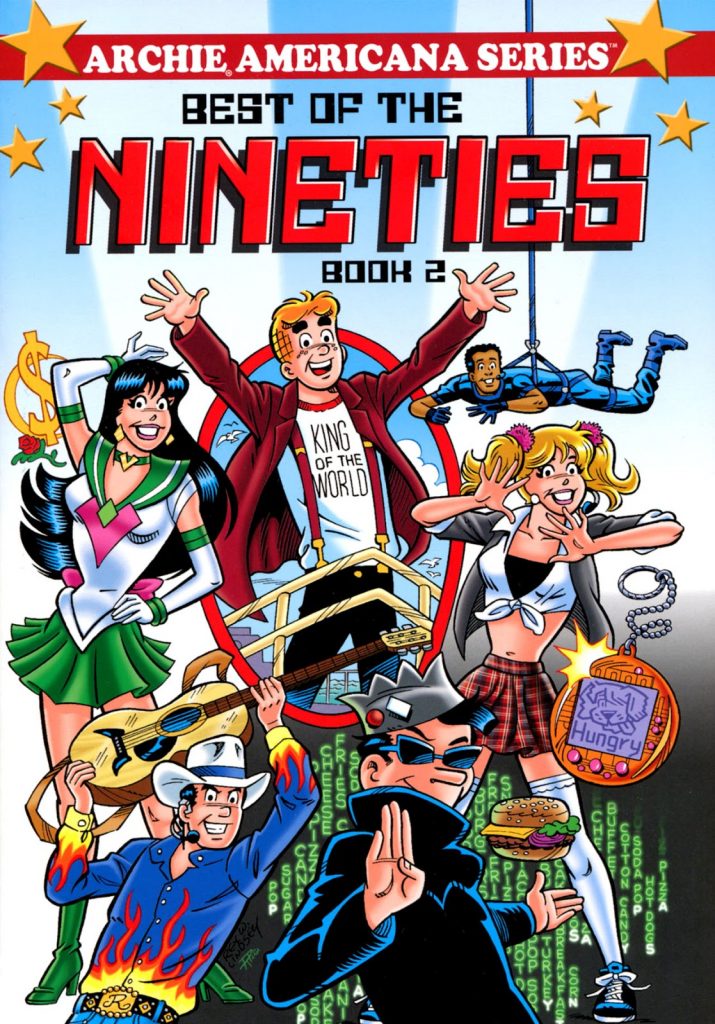

While not entirely moving away from the 1990s fads and fashions, this selection of stories supplies a better representation of material starring Archie and friends, offering some new takes on old themes and some new characters. We start with the Archie Players, the Archie cast reinterpreting film and TV shows, very much in the long-running satirical manner of Mad Magazine, or Cracked, to which writer George Gladir was a regular contributor. However, for Archie he provided far gentler satire with the interpretation having as much to do with Archie and pals as the subject. Gladir’s better on ‘Archie’s Interactive Comics’, where it’s pretended that readers guide Archie’s behaviour and options.

Other scenarios are more familiar. One wonders how many times between them Frank Doyle and Dan DeCarlo have produced a strip about Archie/Betty/Jughead/Veronica trying out a new fashion only for the adults not to understand. Of course, it’s a solid six page gag every time, whether referring to floral kaftans in the 1960s or grunge fashion as here. Similarly, movie stars or musicians stopping by in Riverdale generally have a predictability, but while Renaldo DiHatrio’s visit adheres to the template in Gladir’s story, Tad Britt’s visit by Bill Golliher has a pleasingly different outcome.

There’s a definite broader cast to Archie in the 1990s, and we see more of them than in the first book, with Cheryl, Ethel, Dilbert, Midge and Moose, and a fair amount of Principal Wetherbee. Chuck has developed from the token African American in the background to someone with a character, and he’s identified as the best cartoonist at Riverdale High. Wouldn’t it be interesting if Archie took the next step and tried to create a series around him?

Stan Goldberg provides Chuck’s actual art, and both pages of the sample art, which is only fair considering he’s responsible for drawing as many stories here as the remaining artists put together. Even by Archie’s standards, there’s an exemplary clarity about his pages, and without being told, you’d never guess that his pages are the work of a man already with a forty year career behind him at the start of the 1990s. He obviously makes the effort to look out of the window rather than drawing what he remembers from decades previously.

After a poor showing with naming the people responsible for the first Best of the Nineties book, this time Archie do credit the creators of individual stories, which is welcome. It’s a nice final touch to a generally pleasing collection. It’s also worth a comparison with Best of the Forties to see just how much Archie has changed over the years.

This content is combined with the first Best of the Nineties, and the two Best of the Eighties collections as The Best of Archie Americana: The Bronze Age.