Review by Karl Verhoven

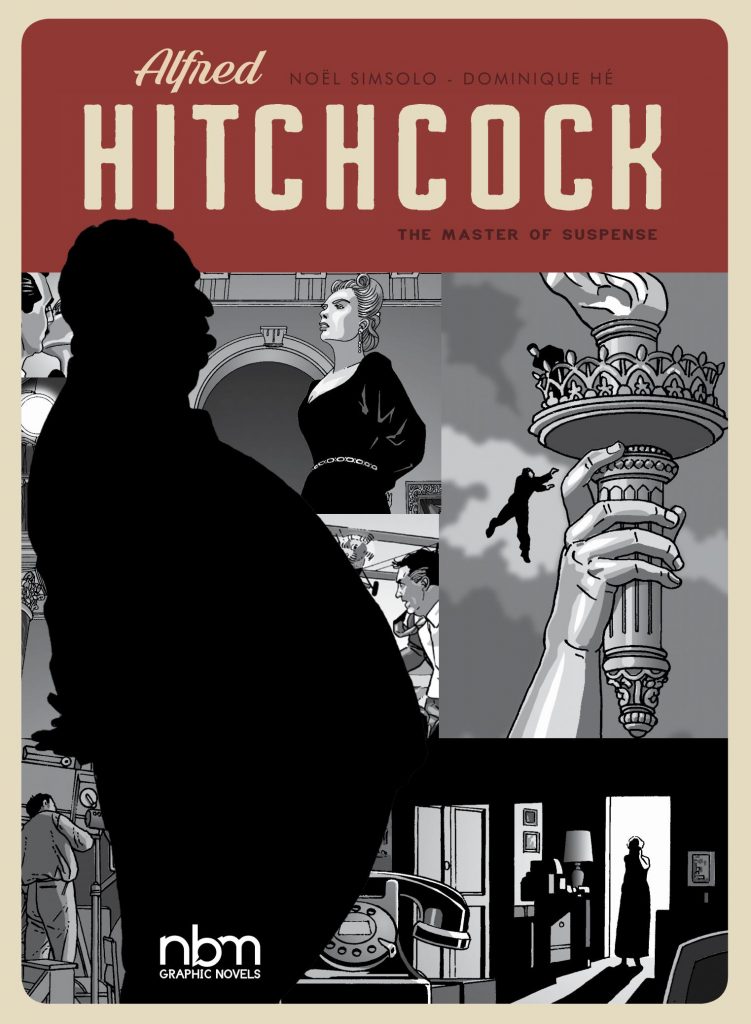

While respected throughout the world for his films, has there ever been a visually fascinating subject more suited to a graphic novel interpretation of his life than Alfred Hichcock? He was portly from a young age, and facially distinctive, heavy-lidded, jowelled and balding by the time of his greatest acclaim, characteristics Dominique Hé is able to maximise. Hé also has a vast photographic record to plunder, as Hitchcock knew the power of an image, so was very self-aware when photographers were around.

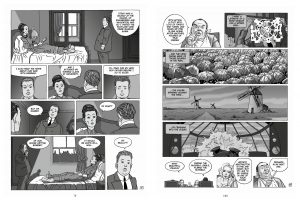

In person he was a raconteur and had a pithy epigrammatic wit, further characteristics making for rich biographical detail, and well exploited by Noël Simsolo. He chooses to have Hitchcock tell his own story, working through formative incidents from early youth, interrupted by sequences from later in life, yet always in snippets, never more than three pages at a time before moving elsewhere or back to the original conversation. Over the first half of 300 story pages much of Hitchcock’s progression from youth to director is related via a chat with Cary Grant on a 1954 film set. Simsolo shows the young Hitchcock learning techniques all the time, as he gradually makes himself indispensable.

Hé is noticeably less able to capture Grant’s likeness, but that’s perfectly excusable given the richness of his art overall. From the turn of the twentieth century to Hitchcock’s last active years in the 1970s, Hé supplies detailed locations no matter where a scene is set, with opulence a speciality, be it internal décor or a spectacular landscape. He almost brings colour despite working in monochrome, presumably a decision reflecting most of Hitchcock’s films being black and white, and uses that to echo Hitchcock’s cinematic precision.

While having a fair bank of Hitchcock quotes to sift into his biography, “all actors are cattle” for one, Simsolo’s dialogue is careful. Too many graphic novel biographies slump when the writer opts to put words into their subject’s mouth, but this Hitchcock is disarmingly convincing. The glee transmits as he notes “Though none of my films had been released yet, I was the highest paid director in all of England”. Grant is, though, too often the sounding board. On other matters there’s a subtlety to Simsolo’s script, showing us Hitchcock’s influences, then a couple of dozen pages later having him lie about them, always aware of what’s a more palatable story. There are places where those who’ve studied Hitchcock’s films will also find visual references planted into the biographical sequences.

Over the book’s second half Hitchcock discusses matters with a greater variety of people. A love of film and theatre informs his work, but we learn of other continual influences such as the fear of physical violence, Catholicism, and blondes, alongside lifelong habits such as pranks. Simsolo offers insights into the making of many films, exploring subtexts Hitchcock couldn’t make obvious at the time. This is all achieved with a panache one suspects Hitchcock would have admired, especially a pleasantly understated selection of scenes where Hitchcock discusses his work or its reception with his wife.

A couple of typos with dates irritate, one moving a party forward a decade to two years after Hitchcock died, and if there’s a slight fault with Alfred Hitchcock: The Master of Suspense it’s that after such a detailed menu, 1958 to Hitchcock’s 1980 death are covered in just thirty pages. Otherwise Simsolo and Hé bring Hitchcock and his films to life. Everyone who reads their biography is not only getting a fully engaging work about a remarkable man, they’re simultaneously being invited into watching the Hitchcock catalogue.