Review by Frank Plowright

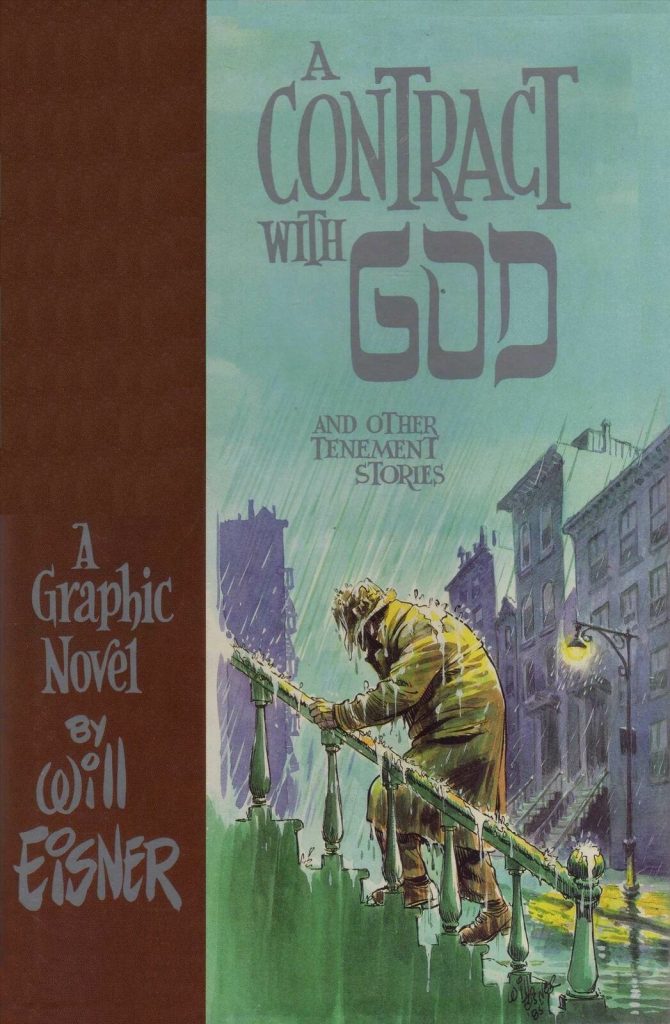

A Contract With God and Other Tenement Stories is frequently referred to as the first graphic novel, with the term’s origin ascribed to Will Eisner. Neither is the case, with Eisner acknowledging Lynd Ward in the introduction to the first edition, but while Eisner may not have broken new ground he was hardly following a well trodden path, and was messianic about promoting the idea of the graphic novel.

What Eisner produced in 1978 is four short stories connected by their being located in a tenement block during the 1930s, and their being locked into Jewish culture. This was new ground for comics, although had literary antecedents, and Eisner channels the recollections of his own youth in spotlighting trades now vanished, investigates the wider aspects of Jewish history, religion and culture, and trades in dreams. Frimmie Hersh, protagonist of the title story, fled the Russian persecution of Jews in the 1880s, Marta Maria sees a chance to renew her stalled singing career via a stand-in, and tyrannical building superintendent Mr. Scuggs is revealed for what he is.

Sentimentality would later feature strongly in Eisner’s work, but there’s little to be found in this collection of shattered dreams, human weakness and callous manipulation. There are no heroes, just protagonists, and Eisner’s very adept at providing an understanding of their characters. Hersh is a shattered man who believed devoting his life to good works would earn consideration from God, and the street singer whom we presume to be one thing actually only has the single redeeming quality.

The four stories still read as strongly as they did in 1978, but the art no longer stands out as it once did, partly due to Eisner’s own success. He was able to issue further graphic novels, and we’ve now become used to his personality-rich portraits, his storytelling frequently lacking panel borders and the uncommon page layouts. In 1978 these came like a bolt from the blue when compared to even the more accomplished standard American comics, but while the art remains memorable, the innovation has evaporated, and some emotional reactions now seem very staged.

After three tortured tales, the final story supplies some joy, although it doesn’t hold throughout. Eisner defines the summer treat of ‘The Cookalein’, when poor tenement residents rent a place in New York state for two weeks, doing their own cooking. Carrying the slimmest plot, the level of observation from anticipation to return is remarkable. Eisner extrapolates the freedoms on offer via the change of location, enabling personality transformations, sexual exploration and growth. It’s an under-rated gem.

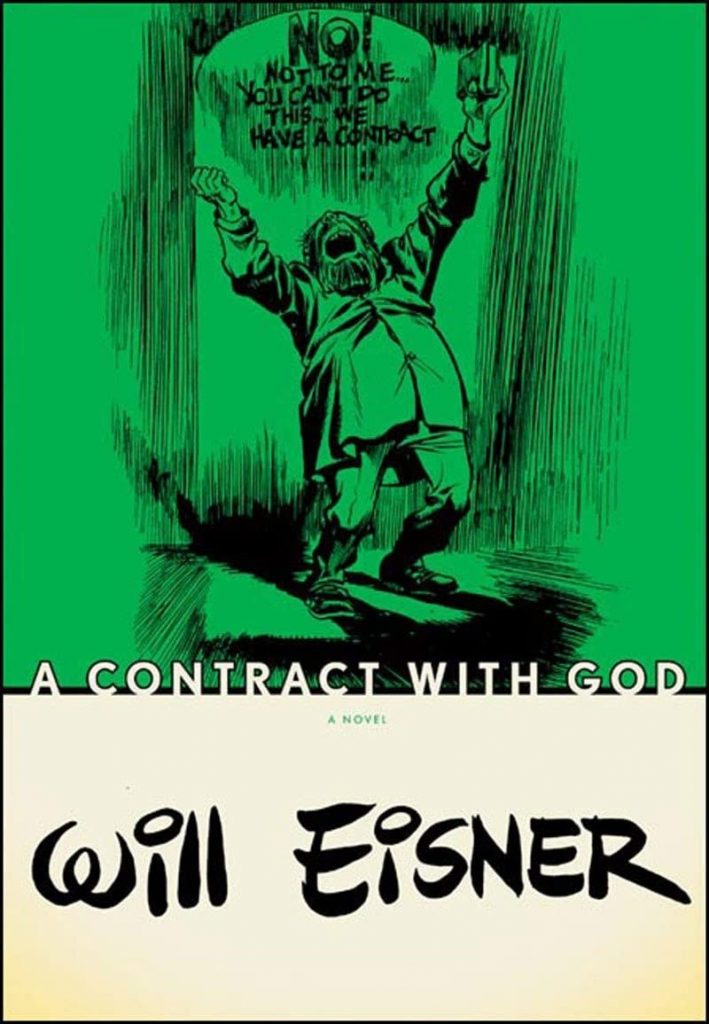

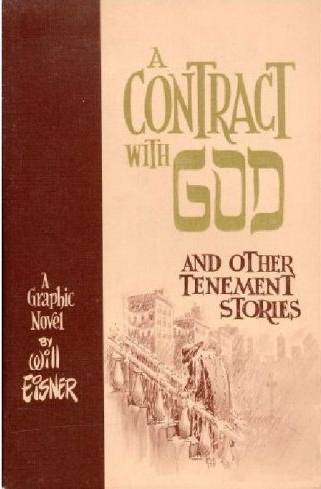

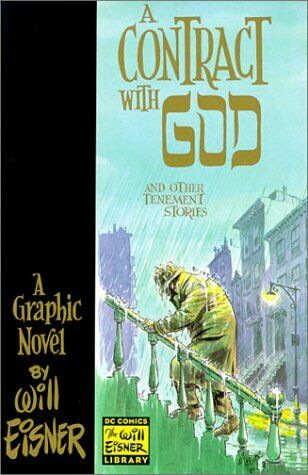

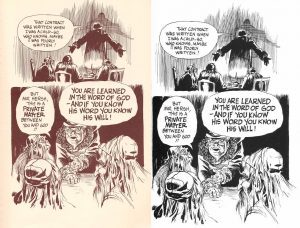

Once a landmark, now just part of Eisner’s praiseworthy back catalogue, A Contract With God is also a signpost to themes Eisner would return to several times over the following twenty years, with Dropsie Avenue the nearest to an actual sequel. It’s combined with that and A Life Force in The Contract With God Trilogy. A Contract With God itself has only rarely dropped out of print, with the most recent edition issued in 2017 to celebrate the centenary of Eisner’s birth. One feature, however, distinguishes the first edition from the remainder, many issued under Eisner’s direction, so at some stage he decided the brown art on sepia-toned pages originally used were better replaced with black and white. The sample spread provides a comparison.