Review by Graham Johnstone

With ten books (in English translations) to his name, by the time of 2008’s The Last Musketeer, Jason was an acclaimed creator, praised particularly for his storytelling finesse and emotional resonance.

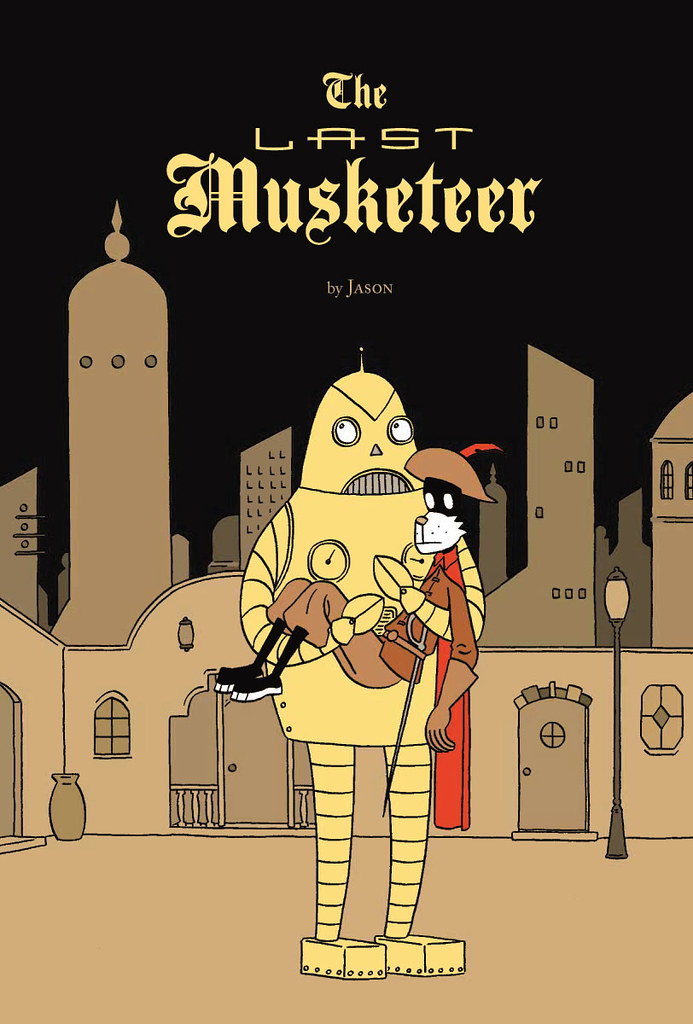

Jason’s art style is highly distinctive: simplified anthropomorphic characters, rendered in the ligne claire style made famous by Hergé. Often, as here, it’s enhanced by the elegant flat colours of the similarly single-named Hubert.

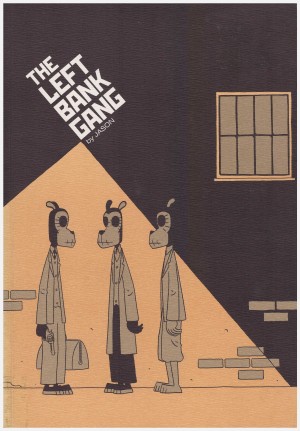

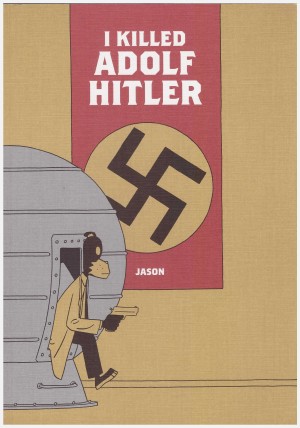

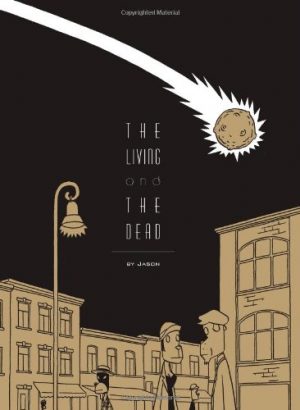

Jason’s visual consistency can disguise his literary and conceptual versatility. Looking at only the few books immediately prior to this, The Left Bank Gang (2006) is nominally about Ernest Hemingway and (the mostly ex-pat) literary community in inter-war Paris; and 2007’s I Killed Adolf Hitler involves a time-travel plot. Both are rooted in fact, but as springboards for Jason’s narrative experimentation and oblique character studies. The Living and the Dead, (also from 2007) is indeed about zombies amongst the living, and as a genre re-appropriation, points most directly to this volume.

The Last Musketeer, is Athos, the eldest of the three from the swashbuckling novel. Original creator Alexandre Dumas had already revisited the Musketeers in subsequent decades, and Jason extends the story into the present day. We meet Athos in a Paris he hardly recognises. He’s yearning for the past, and still “drowning his secret sorrows in drink”, whenever a fellow barfly will stand him one. Jason makes Athos less taciturn than reputation, so enabling some charming soliloquies, and man-out-of-time commentary on the modern world.

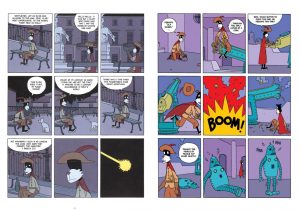

Fun is had with the swashbuckling staples of combat, capture, escape, a commandeered vessel, and more – all packed into 48 intricately plotted pages. Such a story surely requires a climactic one-on-one sword fight, and it’s delivered with a satisfying twist. However, Jason is too creatively restless to simply adopt a genre, and here mashes up the swashbuckling source material with its interplanetary offspring, notably Flash Gordon. The latter’s inciting incident of an attack on Earth, hits Paris (pictured, left), and offers Athos a purpose, and escape to a alien world that’s reassuringly familiar.

Jason playfully subverts the genre. His princess, thankfully, is no fawning damsel. He also offers an ironic commentary on fiction itself. An amusing example being Athos pulling the ‘sick captive scam’, then, while escaping, musing to the duped guards that it’s “quite well known” on his planet. Similarly, the turnaround from Dumas’ taciturn Athos, to the loquacious version here, is cheekily acknowledged by the Musketeer opining without irony, that he doesn’t trust people who talk too much.

The charming cover image of a robot cradling the Musketeer, is striking, without being reducible to a single meaning. There’s a combination of historic and ‘modern’ technology. Musketeers, combining swords with mechanised weapons were already an example of that, but here the muskets are upgraded to ‘zap-guns’. The robot cradles Athos, as if he were not hero, but damsel-in-distress, or perhaps that his timeless honour and decency impress, even on another planet, and even a machine. Jason’s cover, then, neatly sums up the book’s mash-up and subversion of genre expectations, but also the deeper themes represented by Athos, of displacement and obsolescence.

It’s tempting to read Athos as an avatar for the creator, like Jason (real name John Arne Sæterøy) he has a single word nom-de-guerre, and his sense of displacement in Paris may have been felt by his Norwegian-born France-based creator. The title story of Jason’s later Athos in America, supports that idea, as the cartoonist also lived there.

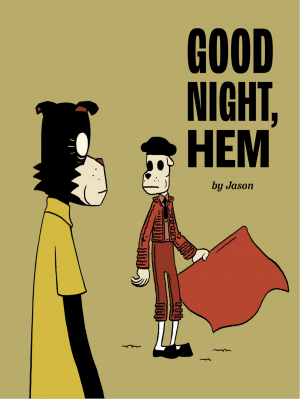

Highlighting Jason’s restless urge for a new angle, the Musketeer meets The Left Back Gang in 2021’s Good Night, Hem.