Review by Graham Johnstone

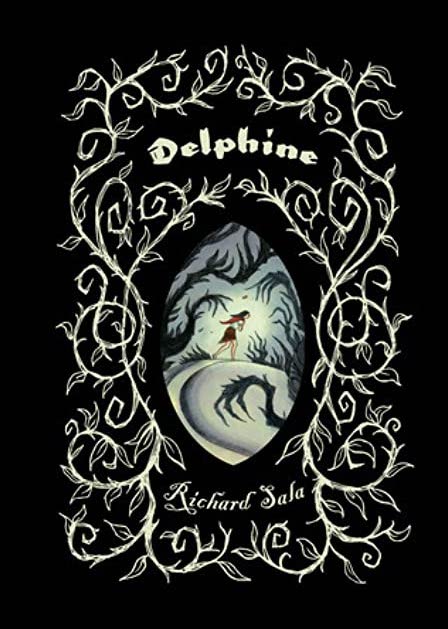

Richard Sala’s work is so distinctive as to disguise his range. Originally known for ironic gothic horror, (The Chuckling Whatsit, Peculia), he danced between genres, latterly revelling in pulp crime (In a Glass Grotesquely). Sala liked to mess with expectations, and mash-up mismatched modes, like the boarding school story and crime caper for Cat Burglar Black. Delphine begins “Once Upon a Time”, signalling a fairytale, though here updated and upended.

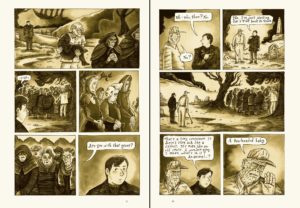

College student Delphine, is drawn back home over the summer, to care for her ailing father. We learn this, however, through the memories of her unnamed suitor. As weeks pass without a letter, he dwells on their last conversation, inferring ominous clues, preceding his quest to find her. It opens with his arrival at a railway station in an unnamed backwater. Modern transportation aside, this might be the ‘once upon a time’ central Europe of the Brothers Grimm. Sala typically reflects his New World origin, but finds a setting where Old World customs might endure, and his revisionist update is through the citified couple.

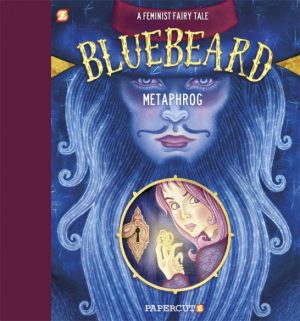

So how updated from stereotypes of heroic princes, and damsels in distress, is this 21st Century story? Sala had a track-record of heroines, so he’s upending his own tendencies here, with a manling as ostensible hero. A plot of Delphine missing and presumed needing rescued, recalls the regressive trope of ‘fridging’. Named and shamed by Gail Simone, it means a female character sacrificed as motivation for a male character. However, Sala’s two leads here defy gendering. Delphine, though only seen through her admirer’s eyes, is the real protagonist. She’s the one who first faces and accepts the call to action, risking herself to save another. Her would-be rescuer is armed only with an address, and feelings of abandonment. Far from charging in on a white horse, he’s dependent on hitching lifts, making him a captive passenger on a road trip through Sala’s unhappy land far far away. He even becomes lost in the woods, needing rescued by a huntsman, so upending another fairytale trope. This ‘prince’ is not even given a name. Delphine, though, derives from the Greek ‘delphus’ meaning womb. This suggests the would-be rescuer is no macho, seeking a battle-prize wife, but craving instead, a mother’s nurture, so further upending a gender stereotype.

Sala, as usual, wraps all his ideas into an entertaining romp, with unpredictable twists and turns. Cheery nods to fairy tales include a stall offering ‘fresh apples’, a wolf kept on a leash by a grandma, and a ‘kiss’ from a toad. Hints of Sala’s main inspiration are sprinkled through these pages, waiting to be spotted on a reread, once their significance becomes apparent.

Sala’s art is also distinctive enough to disguise his range. His early style updated old engravings, with artful hatching that conveyed both shade and form. Latterly, he reduced his rendering in favour of the luminous colour seen on The Bloody Cardinal. Delphine is chronologically and stylistically in the middle, with Sala’s signature hatching replaced by tonal washes. Originally in blue, the pages are reproduced here in deep, velvety sepia, evoking age, and creating subtle shades of darkness.

Originally serialised, this 2012 hardback edition includes the original coloured covers and frontispieces, making it an appealing package. Scarce and costly in either form, a reprinted collection is surely due.