Review by Frank Plowright

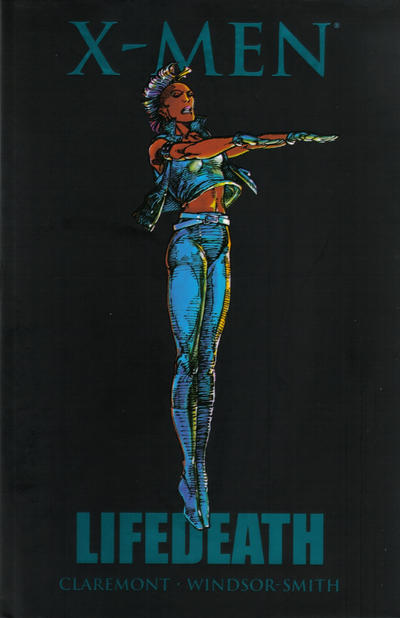

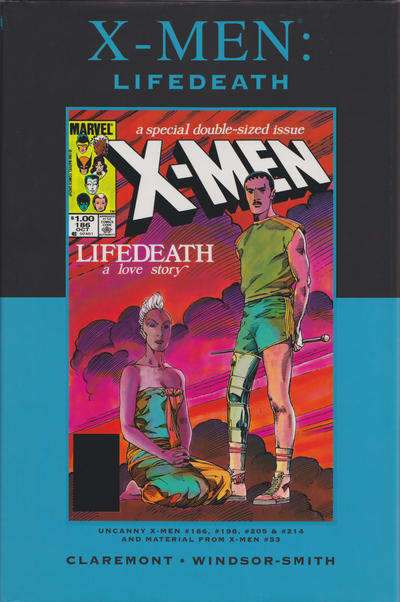

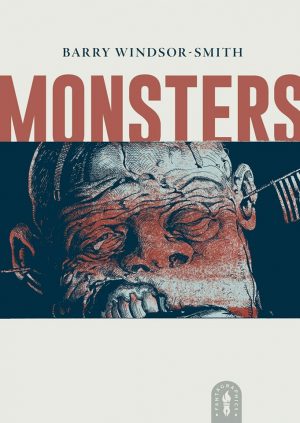

There’s no quibbling with the artistic value of a hardcover package collecting four X-Men stories illustrated by Barry Windsor-Smith in the 1980s. They’re a phenomenal combination of refined technique and creative imagination, and seeing them on quality paper is a joyous experience. Whether it was necessary to end with his crude work from the 1960s is debatable.

‘Lifedeath’ concerns Storm having survived being shot by a strange gun, but losing her mutant abilities in the process, the first time since her early teens she’s has to live without being able to fly or control the weather. It could be likened to missing a limb, and she’s paired with Native American engineering genius Forge, who has conveniently suffered the loss of a leg. He’d been introduced in an earlier X-Men story, but for his purpose in ‘Lifedeath’. Windsor-Smith supplies Storm’s natural grace and bearing and Forge’s self-awareness in a succession of claustrophobic portraits amid the wonders of Forge’s engineered property. It’s very nuanced, and an example of Chris Claremont’s once innovative, but now dated use of thought balloons working to create a story rather than distracting from it. A squirmingly awkward character study may not be what X-Men readers of the time expected, but it smartly allows for changes of scenery, and has a killer pay-off.

A shorter sequel resolves outstanding issues amid Storm’s powers returning a year later. Windsor-Smith is more fully involved, co-plotting, inking and colouring, and that’s a mixed blessing. The art is even more spectacular but the plot more ethereal, relying greatly on illusion and hallucination in conveying conflicted inner torment, while some thought balloons are overwrought. Storm realising others also have problems improves matters in working toward what’s ultimately a tragedy. Marvel rejected a follow-up, eventually published with some changes by Windsor-Smith as Adastra in Africa.

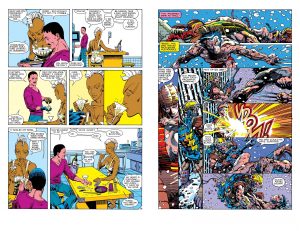

‘Wounded Wolf’ is again Windsor-Smith handling all creative aspects other than script, provided by Claremont, and lettering. The art is again breathtaking, but this time the colouring suffers slightly. Designed to dazzle on pulp paper the little details shimmer too brightly on gloss stock, but the work applied to cybernetic detail over the first few pages is dedication beyond most comic artists. The contrast of the feral Wolverine with the infant Engergizer is well conceived, and this led to Windsor-Smith’s even more spectacular Wolverine stories.

Windsor-Smith only pencils the final 1980s piece, and despite evocative introductory captions from Claremont, it’s slim, beginning with Dazzler seemingly out of control and the X-Men fighting each other. Again. It looks good because Windsor-Smith is good, but lacks the intensity of the previous three stories, and the ending is poor.

It bulks up the book, but was the inclusion of Windsor-Smith’s first Marvel submission from 1969 really necessary? It’s the work of an artist with talent and potential, in thrall to Jack Kirby and Jim Steranko, but then nowhere near capable of approaching either. We all have to start somewhere, but surely some artists have earned the right to have their first hesitant steps forgotten. Arnold Drake’s script is juvenile and there’s nothing to be seen other than promise.

A number of Marvel covers from the mid-1980s round off the book, mainly for New Mutants, and they’re a variable bunch. Some have a poise to the composition, others are what Windsor-Smith knows he can get away with, yet you can bet your mortgage they’ll still be far better than the surrounding issues. Why not head to the Grand Comics Database and check?

Four superbly drawn comics by a master artist in a hardcover with a list price of $25. That has to be a bargain.