Review by Ian Keogh

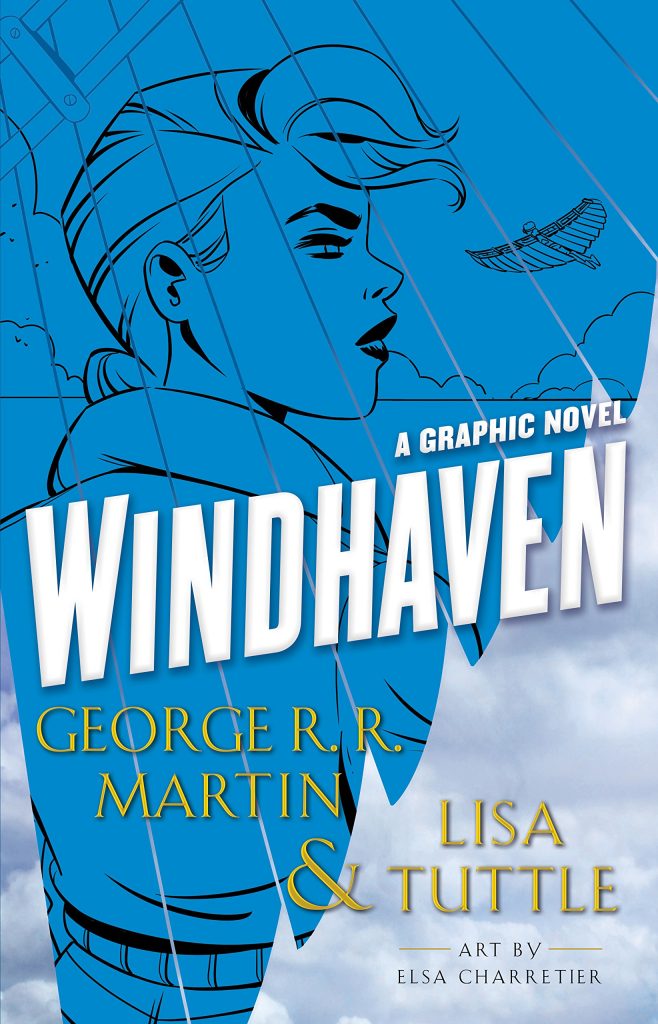

Windhaven began life as a short story collaboration between then aspiring writers George R. R. Martin and Lisa Tuttle in the 1970s, before being revised and expanded for publication as a full novel in 1981. In 2018 Tuttle collaborated with artist Elsa Charretier to adapt the story of a flier on the largely ocean world of Windhaven.

Fliers are much prized on Windhaven, using metal strutted gliding wings able to cover great distances far faster than boats, and acting as official messengers between isolated island communities. The expectations thrust on young shoulders are well aired over the opening pages, which also establish the dangers of flying, and the Eyrie, an otherwise inaccessible sheer rock used by fliers as their meeting place. Maris aspires to fly and has occasionally been allowed to borrow wings, but tradition demands their passing is hereditary. This is because Windhaven was populated when a craft from another world crashed there and the metal to construct new wings isn’t found on Windhaven, information that isn’t as well conveyed as might have been. While a far better flyer than her unwilling step-brother, merit and talent has no bearing on tradition. This efficient world building leads into the political discussion of whether flight should continue to be restricted to the entitled, with everything brought to sparking life by Charretier and colourist Lauren Afee. Charretier’s good at defining personality, especially the passionate Maris, and Afee’s selection of dull and darkened colours spectacularly define a stormy world.

A battle is won in the opening chapter, but entitlement runs deep among the oldest families on Windhaven. The plot makes good use of tradition often being a means of exclusion, extrapolating a version of the European class system, and of the desired outcome of worthy ideals not always being the only possibility. However, for a long period this is conveyed in very broad strokes, the differences of opinion reduced to almost dogmatic prejudice, which could lull readers into believing predictability is the order of the day. It is, but only up to a point, kept fresh by three distinct chapters and an epilogue, each jumping forward through the years. We see Maris as a yearning, but determined youngster, an adult with responsibilities and as an older woman when much about Windhaven’s society has changed and war is about to break out. Each segment poses a distinct ethical consideration, ending with whether the messenger is responsible for the message, or, if you choose to look at that way, how the new boss may well be the same as the old boss. A clever aspect of the final chapter is that it details fighting for the dregs of a now redundant society when a new discovery will rapidly change that society beyond recognition.

In places the discussions become dry, and Maris is never entirely convincing as the personality who carries Windhaven, but the world building and extrapolation of what’s been built indicated the talent of the writers in the late 1970s, providing a story that stands the test of time. For this hardcover Charettier and Afee’s considerable talents provide a new polish for what should be a well received fantasy drama.