Review by Ian Keogh

Hermann Karnau is a recording engineer obsessed with sound in all its forms, especially how it affects people and their ability to communicate. In addition to his professional tasks, he records all sorts of odd sounds for his own pleasure, such as people clearing their throats or sniffling, with a covert recording made in a brothel especially prized. This wasn’t traded with salacious intent, but with a collector’s passion. Contrasting Hermann is Helga, the oldest of six children, whom he meets when dispatched to make an audio recording of their father. She’s bright and cheerful, and it’s best to avoid reading the back cover blurb revealing something about her relatively concealed over the first third of the story. Avid historians of Nazi era Germany may be a step ahead.

Hermann’s a study, not a figure of sympathy, capable of extraordinary bravery without realising it, and extraordinary cruelty in the name of science. His anticipatory excitement about the sounds he might capture overcome any caution about roaming battlefields in daylight to plant his microphones, and he can likewise ignore torture. His capacity for reducing humanity to abstract sounds has a chilling use in a country obsessed with racial purity. Also chilling is Helga coming to terms with her family’s position in the Nazi hierarchy and the privilege and hypocrisy that entails.

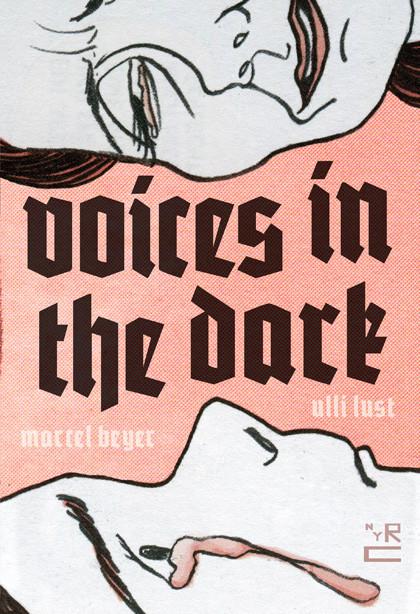

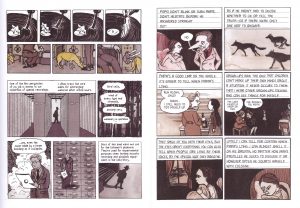

Ulli Lust set herself quite the challenge in adapting Marcel Beyer’s novel. Not only is it an extremely introspective piece of work offering little opportunity for illustrative glamour, but the focus on sound transferred from one silent medium to another hardly lends itself to a visual presentation either. Lust adopts a deliberately simple, almost primitive style of expressionism, still able to convey detail and emotion, although that’s frequently distanced. It’s at its best toward the end, where the characters gather in an enclosed and claustrophobic location disturbingly brought to life.

In theory there should be a powerful pull contrasting the person so concerned with minor detail they’re unable to see the bigger picture, and someone gradually realising the lies governing her life. However, Lust’s ambition doesn’t result in a compelling graphic novel. Hermann’s purpose is to be dull, a representation of mundane humanity’s capacity for infinite cruelty, personifying what was learned about Nazi experiments after World War II. Helga’s is to see what he cannot, yet until the closing stages there’s barely any interaction between the two characters who share the narrative, faithful to form rather than content by ensuring too much is too ordinary. Strangely, in this adaptation at least, if Hermann were to be entirely stripped out, it would make for a more linear, but also more effective story. We can sympathise with Helga, and her voice is equally effective in making the point of about man’s inhumanity to man. Her progress builds towards an event some who’ve studied the period will know is coming, and it’s over the final chapter that Lust finally manages to generate some feeling, although even then the tragedy is diluted by a variety of tellings.

A distanced tone and a commitment to the reality of a dull person mean Voices in the Dark is nowhere near the compelling read expected by the period and setting.