Review by Frank Plowright

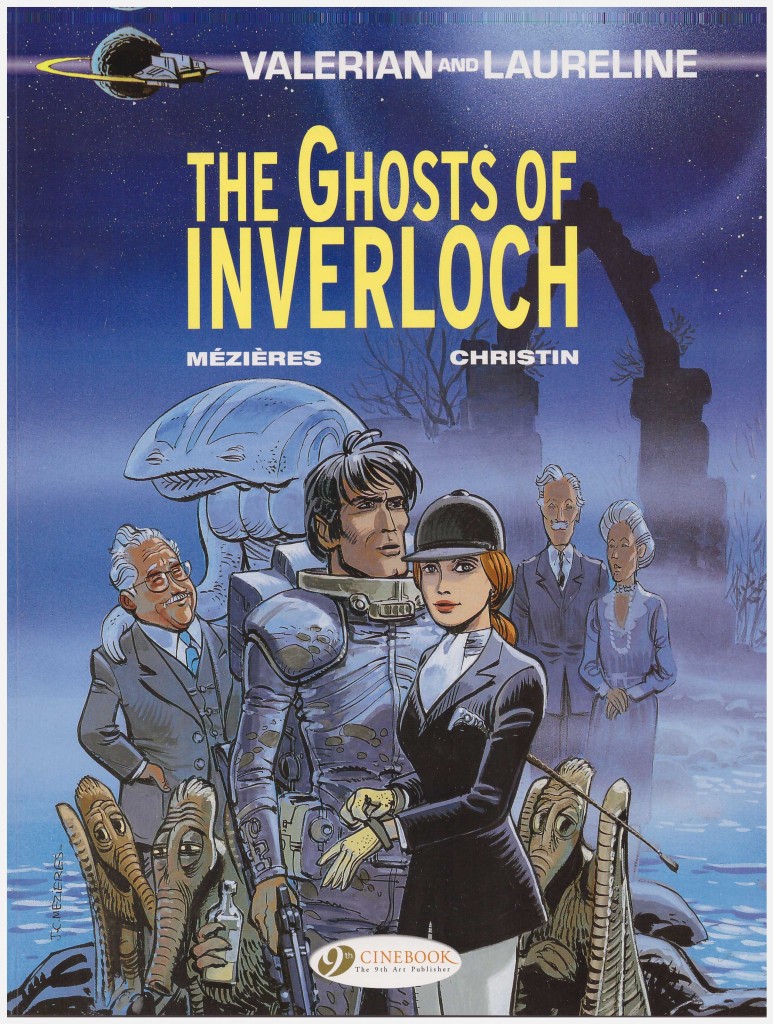

The Ghosts of Inverloch is an atypical Valerian and Laureline story in several respects. It’s firstly a very pastoral tale with very little of the pertinent action involving either Valerian or Laureline, who are reduced for long portions to secondary characters in their own series, a relatively daring departure, particularly in 1983. It’s also a languorous set-up for The Wrath of Hypsis, which completely changes the foundation of the series.

In the introductory volume, The City of Shifting Waters, Pierre Christin introduced his temporal agents, and sent them back to 1986, an Earth after disaster. At the time this was merely a story plot, but after a decade plus of Valerian and Laureline adventures, that date was approaching for real. Instead of discarding the idea, Christin instead embraced it, and while not obvious, this and the previous two graphic novels have threads connecting them with the first.

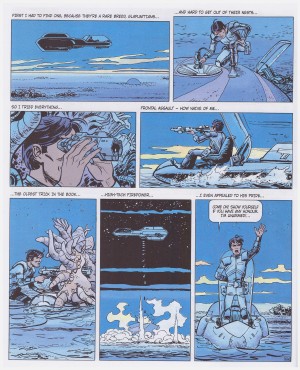

In the remote Northern Scottish estate of Inverloch Laureline accompanies the old Lady Charlotte Seal while Valerian is a few thousand years in the future attempting to lure an odd creature he’s to haul back through time. Both are puzzled by their instructions, which make little sense in isolation. Christin, however, is painting the bigger picture via others. A clever scene introduces characters pertinent to the series, but written as if it’s someone else who’s the focus. There’s also a lengthy solo sequence for Albert, an engaging middle-aged polymath recruited to help temporal agents in the 1980s, and the introduction of a puzzling problem afflicting those controlling Earth’s nuclear arsenal. An expected visitor turns out to be someone entirely unexpected, and accompanied by their baggage.

The creators’ take on British culture is amusing, even-handed and crossing social strata. The creators capture the effortless and imperturbable confidence of the upper classes and the substandard nature of British service systems, presenting a multicultural society, although largely taking industrial action. It’s a bit rich, however, to see a French writer making jokes about British workers perpetually on strike.

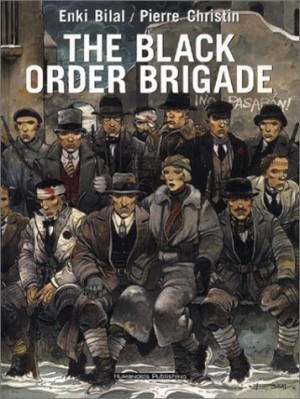

By now there should be no surprises about the art of Jean-Claude Mézières, yet his designs for aliens and alien landscapes continue to surprise. He’s also in playful mood, including characters drawn in the style of Enki Bilal and featured in The Hunting Party, and brief homages to E.T. and Peanuts. Anyone captivated enough by the scenery tempted to visit Inverloch will be disappointed to learn that it’s not real. The Scottish highlands, however, encompass many places of equal beauty.

Despite the place-setting nature of The Ghosts of Inverloch, the skilful instilling of mood and foreboding ensures this isn’t a makeweight book. The queries hang heavy, and the anticipation is high.

Just so there’s no confusion, there’s absolutely no connection beyond the title with Sarah Ellerton’s Inverloch fantasy graphic novels.