Review by Graham Johnstone

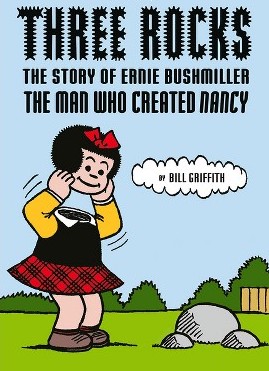

Three Rocks – The Story of Ernie Bushmiller the Man Who Created Nancy, may have readers (particularly in Britain), asking who?

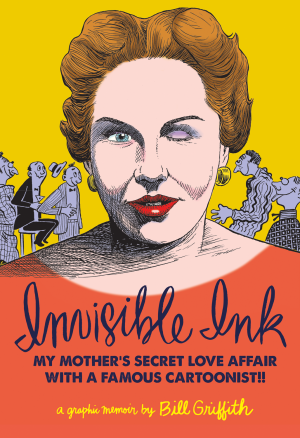

Nancy is an American newspaper comic – massively popular yet minimal, oblique, sometimes surreal. Perhaps its only rival over recent decades is Zippy the Pinhead, so who better to tell the story of Nancy’s creator than Zippy’s creator, Bill Griffith?

Bushmiller’s (cover featured) ‘three rocks’, were a recurring feature of Nancy’s minimal setting, and Griffith’s Three Rocks is effectively three books: biography, art appreciation, and curated collection.

Three Rocks appeared just ahead of a centenary. In 1925, the young Bushmiller took over a strip about wannabe actress Fritzi Ritz. In 1933, her niece Nancy visited, soon becoming the title character, and Nancy’s syndication reached a peak of nearly 900 newspapers. In 2017, two professors wrote a book explaining the language of comics through a single Nancy strip. As of 2025 a rebooted Nancy has renewed popularity. So, Nancy has a story to tell, but Ernie Bushmiller claimed he didn’t.

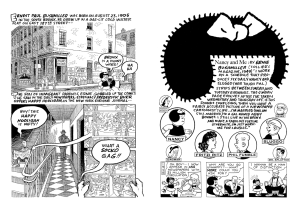

Griffith follows Bushmiller’s journey from comics obsessed kid, to newspaper office-boy, through success and celebrity, to venerable overseer micro-managing other hands. Griffith finds prize anecdotes, like Ernie summoned to Hollywood to write gags for Harold Lloyd, and keeping wife Abby (reputed model for the glamorous Fritzi), away from a hot-to-trot Groucho Marx. A meeting with George Herriman is a spotters delight, comparing inspirations for the settings for Krazy Kat and Nancy. Better still are the insights into Bushmiller’s process, like starting each strip with the final panel punchline or ‘snapper’, and his four desk set-up that let him jump between strips, as inspiration ‘snapped’. A wonderful sequence juggles the demands of daily strips and daily life when Abby asks him to buy a meat grinder (mincer). Griffith sucks us into Ernie’s search for a meat grinder gag, before delivering his own ‘snapper’ – preoccupied Ernie arrives home empty-handed. Griffith compellingly sheds light on Bushmiller, but can he find some shade?

Griffith offers a contemporary and clear-eyed critique of the strip. Bushmiller inserted himself into his strips as (Fritzi’s aptly named boyfriend) Phil Fumble, and as creator (“Who’s got a gag for me today”), so breaking the fourth wall. Griffith inserts ‘himself’ as visible commentator, initially via a lecture at the imaginary Museum of Bushmiller. This enables his overview of Nancy’s evolution, including her ever more schematic appearance, unlike Fritzi, who changed only outfits (usually ‘on camera’). Griffith confronts this cheesecake element, and shudders at the weirdness of pre-pubescent Sluggo, as surrogate for the adult male reader, ogling Fritzi. Bushmiller’s public persona was affable and conservative, but Griffith hints at a shrewder Bushmiller, who knew that cheesecake and universally understood gags enabled his affluent life, and pursuit of his own minimalist aesthetic.

Griffith, proves the right writer, but is he the right artist? His traditional draughtsmanship and laborious pen-hatched shades could hardly be further from Bushmiller’s elegant abstraction. Still, the contrast differentiates Griffiths’ sober biography, from the generous selections of Bushmiller’s strips, and Griffiths’ own ventures into Nancy reality. This includes the epilogue – a rare interview with reclusive former celebrity Nancy Ritz. Griffith pastiches Bushmiller imperfectly, perhaps in a rush to the finish line.

Highlights include numerous Nancy strips (many previously uncollected), a Bushmiller quote typed on Ernie’s 1917 Corona typewriter, MAD and Andy Warhol’s versions of Nancy, comparison with the paintings of Edward Hopper, and a (Griffith konkokted?) Fritzi/Krazy Kat krossover.

Nancy fans will treasure this, and many newcomers will fall for the genius of Nancy and Griffith’s rich, fascinating and judiciously surreal account of the character and her creator.