Review by Frank Plowright

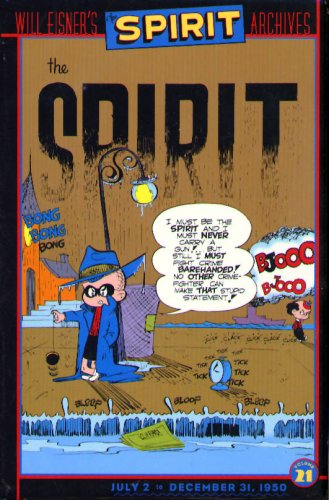

Reading Will Eisner’s Spirit work in bulk is an interesting experience for dispelling the myth that greatness began when Eisner took back control after World War II (Spirit Archives 12) and quality was ever upward from that point. While the overall quality is far higher than most comics produced in the 1940s, within that there is variance, and Spirit Archives 20 presenting the first half of 1950’s output shows it, the artistic standards sustained while the stories aren’t as consistent. Well, the second half of 1950s output shoots the quality level back up considerably.

Strangely, the quality upswing is partially down to less work from Eisner himself, perhaps stretched too thin over the first half of 1950. He trusts Jules Feiffer with most of the writing, and other artists are now used occasionally, although apart from a deliberately different final story, Eisner remains heavily involved with the art, to the point where only the expert can identify the pencils of Jerry Grandenetti through Eisner’s inking. However, two of the three stories Eisner writes are memorable, the lunacy of appointing the seductive P’Gell as a school French teacher, and the introduction of Darling O’Shea, the world’s richest ten-year old. The joke is that she’s Katherine Hepburn in disguise, as worldly and capable as an adult, while given to conniving and melodrama. She makes several return appearances, all of them funny, and some poignant.

It’s Feiffer’s writing, though, that refreshes the strip. As with O’Shea, Feiffer takes the recently introduced Dick Whittler, quiet but tenacious detective, and builds some great stories around him, and easily adapts to several other Spirit specialities. He provides exotic locations, themes such as sound, and heartbreaking narratives of the unfortunate or whimsical stories of the ridiculous where the Spirit’s only participation is in the final panels.

Having the weight of creating most stories taken from him means Eisner’s able to spend even more time on the art, and the pages drip with atmosphere. The almost wordless sample pages provide everything an aspiring artist needs to know about cinematic storytelling, and how to create an attention-grabbing splash page. As ever, the personalities are visually stunning, O’Shea’s depiction vacillating between charming and commanding, the ridiculous sight of the Spirit in college clothing, the heartbroken murderers, and the seductive P’Gell, while the action just flows so smoothly.

By 1950 Witch Hazel’s appearance in a Halloween story and a sentimental Christmas story have become Spirit traditions, the Christmas story a beautifully balanced observation on the Christmas spirit. Feiffer adds a Thanksgiving special, ensuring it doesn’t become too sentimental via self-aware captions breaking the fourth wall. During the rhyming doggerel Feiffer notes the prevalence of some terms in creating comics, and has the narrator forget which of the evocatively named gangsters is associated with which location. His experimentation peaks disturbingly in the final strip, which begins with his back-up character Clifford satirising the Spirit and ends with the artist murdering the reader. The very different styles of Feiffer and Eisner combine well for the art.

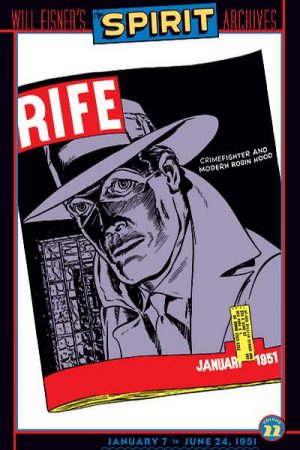

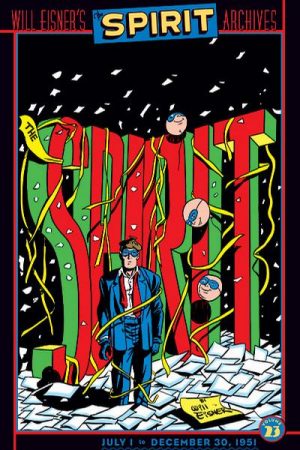

Ranking a Spirit volume so highly when Eisner contributes so few strips may seem heretical, but that undervalues Feiffer, whose later progression far eclipsed Eisner. A loving, anecdotal introduction from Darwyn Cooke completes the package. As a complete volume, though, this is a final hurrah for sustained quality. Spirit Archives 22 follows.