Review by Karl Verhoven

Season of Mists is the first bona fide Sandman masterpiece, the first volume to truly merit the lavish praise bestowed on the series as a whole. It shouldn’t be forgotten that while Neil Gaiman is an exceptionally talented and imaginative writer, Sandman was very early in his career, and he’s noted himself that writing the title was initially a case of learning on the job. The lessons entwine over a taut eight chapters with rarely a wasted word.

There are numerous reasons this works so well, but primary among them is the manner in which Gaiman gathers scraps he’s dispensed over the stories to date and incorporates them into a coherent narrative. Another is that many individual chapters have a distinctly different tone.

Sandman, or Dream, or Morpheus, has been engraved as one of the Endless, seven immortal beings overseeing aspects of human condition, and we open with a family meeting (via a summoning process Gaiman has modified from Roger Zelazny’s Amber books). This is a superbly strained and malevolent occasion, and among the discussion is comment on an incident related in The Doll’s House causing Morpheus to conclude he must visit Hell to rectify matters. This isn’t as simple as might otherwise be, as in retrieving his possessions in Preludes and Nocturnes, Morpheus angered Lucifer, one of the few beings whose might enables him to challenge the Endless, should he so desire.

To pick, the centuries old occurrence that prods Morpheus to visit Hell was arrogant cruelty when originally related, and it’s odder still that he only takes on board he was wrong when this is pointed out.

The situation Morpheus finds himself in is not at all what he expected when he planned to confront Lucifer. Gaiman uses the situation he’s developed to delve into some big questions, explore the Endless, extend his mythology and throw in numerous classical references. Between all that there’s space for a scabrous pastiche of the British public school system via the introduction of Edwin Paine and Charles Rowland, later to star in Dead Boy Detectives: “I was headmaster here from 1901 to my death in 1916, and I am headmaster here today.” Best of all, the initially awkward, and occasionally poor dialogue and captions are now consigned to the past. This is very evocative writing.

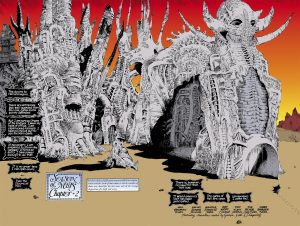

Kelley Jones illustrates most of the story in his ornate style, yet still manages possibly the most gruesome kiss ever illustrated, tongues included. His work shines with a variety of inkers. The opening chapter is an accomplished character study and the series swansong for Mike Dringenberg who defined the early look of Sandman, and Matt Wagner excels with the public school sequence.

This content is within the oversized Absolute Sandman volume two, a hardback slipcased edition also containing the following A Game of You, and selections from Fables and Reflections. Alternatively it’s in the first volume (of two) of the Sandman Omnibus. For those wishing to delve the hidden depths of background material, there’s also The Annotated Sandman, with the same content as the second Absolute edition, but in black and white with copious notes on a panel by panel basis explaining Gaiman’s influences, thoughts, and the ties the stories have to the wider DC Universe.

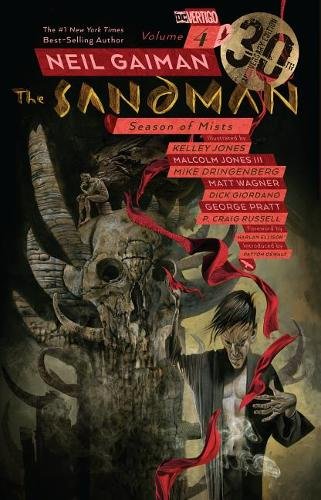

Those on a more selective budget are advised to locate a post 2010 printing, as these utilise the reproductions re-mastered and re-coloured for the Absolute books. Earlier editions have an occasional muddiness and lack of clarity.