Review by Cefn Ridout

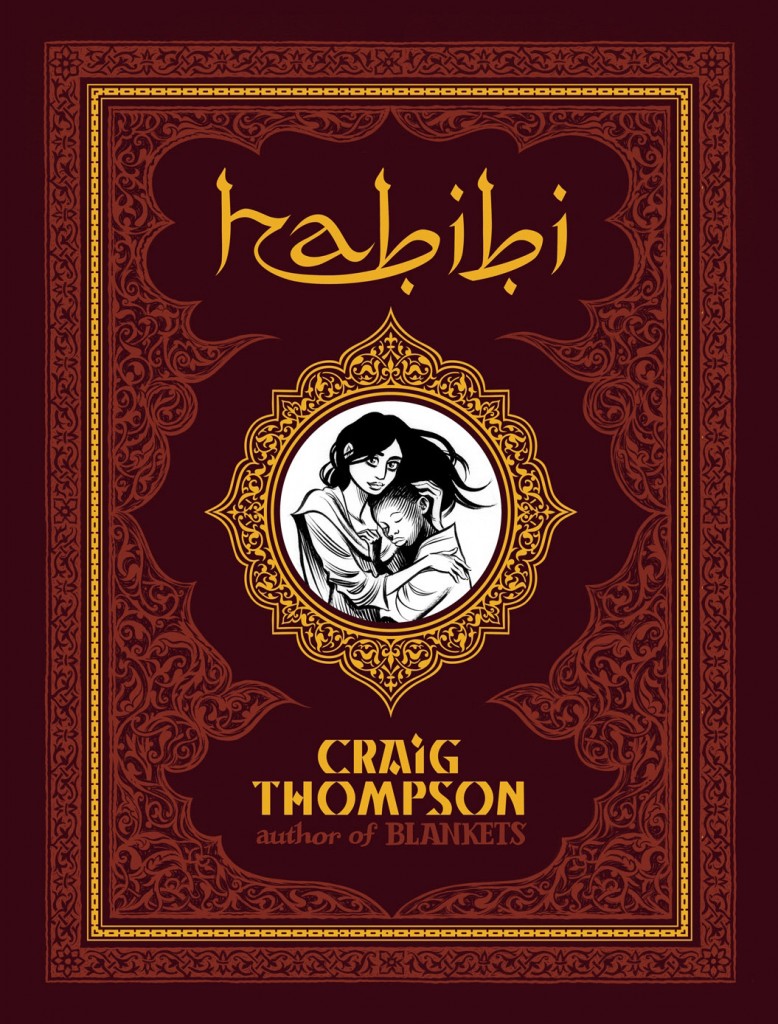

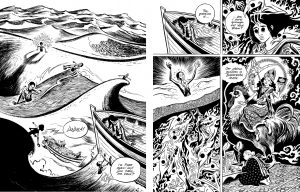

In Habibi, Craig Thompson vividly demonstrates the seductive power of the line. A line that draws together past and present, scripture and history, text and image, ink and blood. A line that inscribes Arabesque patterns and Islamic calligraphy with the same grace that it fleshes out the human form and brings to life a fully realised world. And it’s on extravagant display throughout Habibi, a sprawling, elaborate fable that takes its cue from The Arabian Nights.

Set in Wanatolia, a fictional Middle Eastern kingdom straddling ancient and modern cultures, a smart, spirited young girl, Dodola, is sold into marriage and later kidnapped by slavers. At her auction, she flees with Zam, a timorous orphaned boy she calls “Habibi” (Arabic for “My Darling”), and finds sanctuary in an abandoned boat in the middle of the desert. Here they live for nine years as Dodola entertains and enlightens Zam with tales from the Qur’an and the Bible, while secretly prostituting herself to passing caravans for food. One day, Zam follows her and watches helplessly as she is raped, something that shames and haunts him for the rest of his life. Soon after, Dodola is forced into service at the Sultan’s harem, leaving Zam home alone. Over the next six years, their lives take traumatic twists and turns as they inch towards reunion.

Thompson’s magnum opus is, above all, a novel of ideas. Perhaps too many. Constructed as a grand romance pitched precariously between Orientalist fantasy and magic realism, with forays into satire, socio-political commentary and historical analysis, Habibi struggles to negotiate these thematic shifting sands, ending up stranded on the author’s heroic ambitions. And its ill-fated protagonists fare little better.

Dodola’s gift for storytelling and finding trouble, casts her as Scheherazade by way of The Perils of Pauline, while Wanatolia’s sultan is little more than a lecherous, loony-tune caricature of King Shahryar from 1001 Nights. Yet, some of the harshest judgement is visited on the hapless Zam, whose crushing guilt at lusting after Dodola, his surrogate mother/sister, drives him to desperate measures. This only accentuates the book’s mounting sense of misery and indulgent self-loathing; it’s hard to care about characters that all too often serve the author’s best interests only to see them routinely punished to revive a flagging storyline.

Yet, it’s Thompson’s construction of an Orientalist playground to tackle issues around sexuality, religion, environmentalism and capitalism that really underscores the book’s identity crisis. And he’s done himself few favours conceding to “having fun (with) Orientalism as a fairy-tale genre like Cowboys and Indians”, while simultaneously challenging the genre’s inherent racism and misogyny. Indeed, it’s often hard to tell whether Thompson is lampooning Orientalist tropes or exploiting them, especially in his treatment of the frequently disrobed Dodola, whose persistent sexualisation, abuse and exoticisation, far from turning the male gaze in on itself, risks doing quite the opposite.

This isn’t to doubt Thompson’s sincerity, just his approach. Habibi is, in part, a clear riposte to the uninformed anti-Muslim sentiment that swept the US in the wake of 9/11, which Thompson artfully counters by revealing the shared origins of Islam and Christianity. Habibi is also a sweeping, occasionally moving love story elevated by some sublime storytelling and sustained visual virtuosity. However, at 672 pages, the narrative’s recurrent themes exhaust patience and sympathy, and even the obsessively beautiful brushwork eventually drives the reader to distraction.

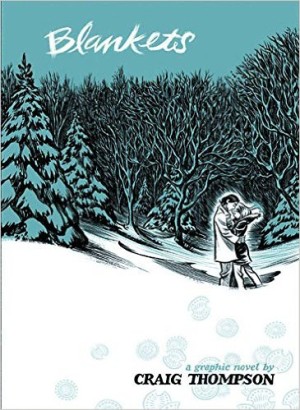

In Habibi, Thompson comes across as a graphic novelist in full command of his craft, with boundless intellectual curiosity and chutzpah, but lacking the restraint to effectively marry his art and ideas in a less showy and more coherent and compelling work.