Review by Frank Plowright

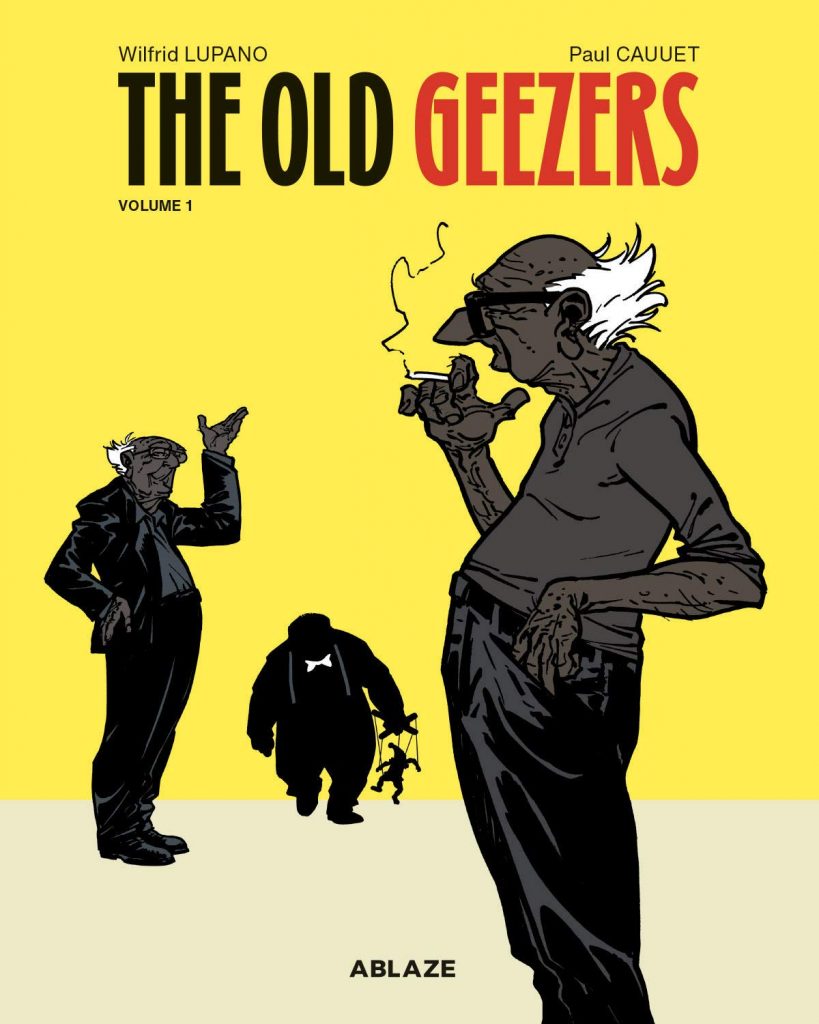

The Old Geezers is a great success all around Europe, with six volumes, the first two combined for this translated edition, and a 2018 movie. This is perhaps surprising as it plays against type for a graphic novel audience due to three of the four main characters being pensioners.

Friends of longstanding, Antoine, Milsey and Pierrot have more in common than is first apparent. Pierrot has drifted through life broadly following his anti-capitalist instincts, and continues social protest in Paris, leading a group of blind people who disrupt fancy events. Milsey seems more compliant, perhaps timidly so, and now lives in a nursing home, yet holds his achievements close. Antoine was once a union activist, and we meet all three at the funeral of his wife Lucette, a firebrand in her day, and with whom his pregnant grand-daughter Sophie shares many characteristics, not least a cynicism about the world. This isn’t just laughing at the old folk, as there’s an unusual depth to the backgrounds. Their stories may have been repeated many times, but represent lives lived, passions and a wealth of experience, which Wilfrid Lupano brings out extremely well.

If the scripts are good, the art is even better, Paul Cauuet’s expressive cartooning gloriously nailing the personalities in all their aged awkwardness, wrinkles, jowels and skin folds represented, yet unless compromised by the indignities of age, respect is the order of the day. The same applies to Sophie, except the awkward realities of pregnancy frequently intrude. Cauuet’s lavish with details of the countryside and more urban surroundings,

Opening story ‘Alive and Still Kicking’ delves back into the secrets of the past and lives unwillingly connected through masterfully plotted sitcom drama. It’s self-contained, with Lupano drawing his plot threads together very satisfyingly by the end. ‘Bonny and Pierrot’ suddenly gives Pierrot the funds to ramp up his disruptive activities. They’re delivered via an alias, yet readers already know the source, and it enables Lupano and Cauuet to have considerable fun showing what he and his friends get up to. The first protest seen is pensioners occupying the trendy bar that’s replaced the neighbourhood bistro, the thinking being that a few weeks of them as customers in quantity ensures no youngster will want to go there and it will close down. This type of creative anarchy extends throughout, Lupano delighting in introducing a lot more old people, some with specialist talents, as explained on the sample art. It’s counterpointed by Milsey and Sophie, now with a daughter, reviving her grandmother’s puppet theatre. The complications are every bit as twisted as the opening story, giving events a beating heart, and in both cases Lupano makes good use of France’s 1960s cultural turbulence.

In addition to supplying first rate comedy drama, Lupano has a few home truths to supply via the cast, whether aged, or Sophie’s take on how a decaying planet is the legacy of the post World War II generations. It’s the pathos, self-awareness and comedy of Still Game handled even more deftly. Don’t be put off by this being a translated edition from a small publisher, it’s worth every one of the five stars, and don’t miss the equally good sequels in Volume 2.