Review by Ian Keogh

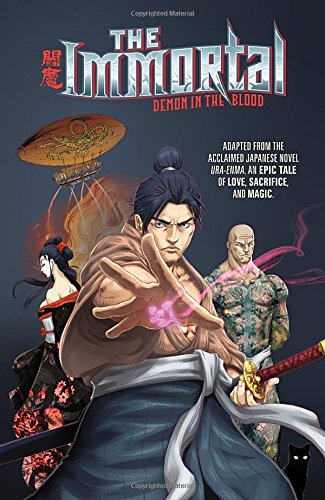

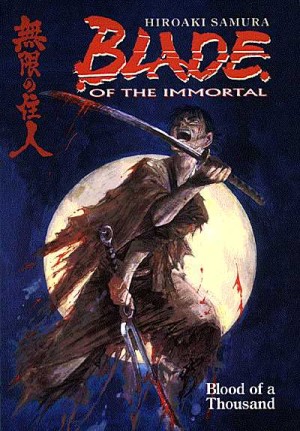

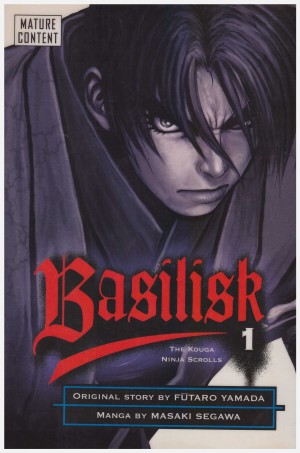

Fumi Nakamura’s debut novel won the short lived Golden Elephant Award, and was translated into English as Enma the Immortal. Dark Horse applied a more fanciful title for the graphic novel adaptation. It features many staples of the better known Manga, featuring immortality, demons, post-feudal 19th century Japan and the hero who’s tragically removed from those they aid.

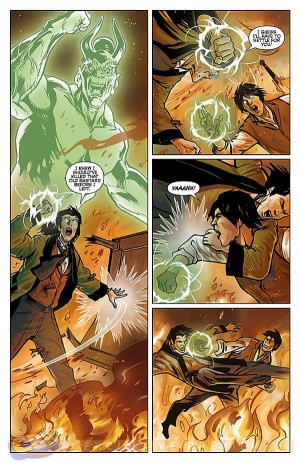

Amane Ichinose is the immortal of the title. Left for dead after a sword fight, he fortunately managed to crawl to a person who could not only heal him, but teach him the art of tattooing and bestow everlasting life. This process, however, requires the implanting of a demon within the soul, a process it’s explained that will never result in happiness, no matter how deep the desire for life. Amane, however, isn’t the only person hosting an immortal demon within, and some brutal deaths occur along the way.

It’s an odd brew. There are some fantastic ideas here, not least the embedding of demons via tattoos, but also some right old tosh, much of which must be laid at Nakamura’s door, problems with the adaptation notwithstanding. Some misdirection occurs, and that’s always good, but unfortunately when the culprit is revealed it’s as likely to induce a groan of disappointment at the lack of originality as it is to engender a frisson of terror. A further oddity is setting the story in a steampunk version of Japan that in the adaptation at least has absolutely zero relevance other than window dressing, and as it only manifests around halfway it’s an odd introduction.

For anyone who’s not read the original work it’s difficult to know whether the stop/start nature of the reading experience is due to that or the compression necessary to adapt the novel. Ian Edginton’s version jumps five years after an opening page that has no relevance until late in the book. Amane’s previous life seems oddly distanced and random, not fleshed out, and it detracts from relationships required later to propel the plot. Elsewhere he’s well characterised as upright, repentant and uncertain in coming to terms with what he can now do.

Vicenç Villagrasa holds his end up. His characters convey their feelings and personalities, the demons he designs have a cultural reverence and an imposing presence, and his steampunk robots have a shine. He relies very much on close-up depictions when varying the distance of viewpoints might occasionally be more dramatic, but that’s well within artistic choice.

At its best The Immortal is engaging, and a story that would easily transfer to film adaptation. It ought to appeal to anyone with a fondness for Japanese period drama.