Review by Frank Plowright

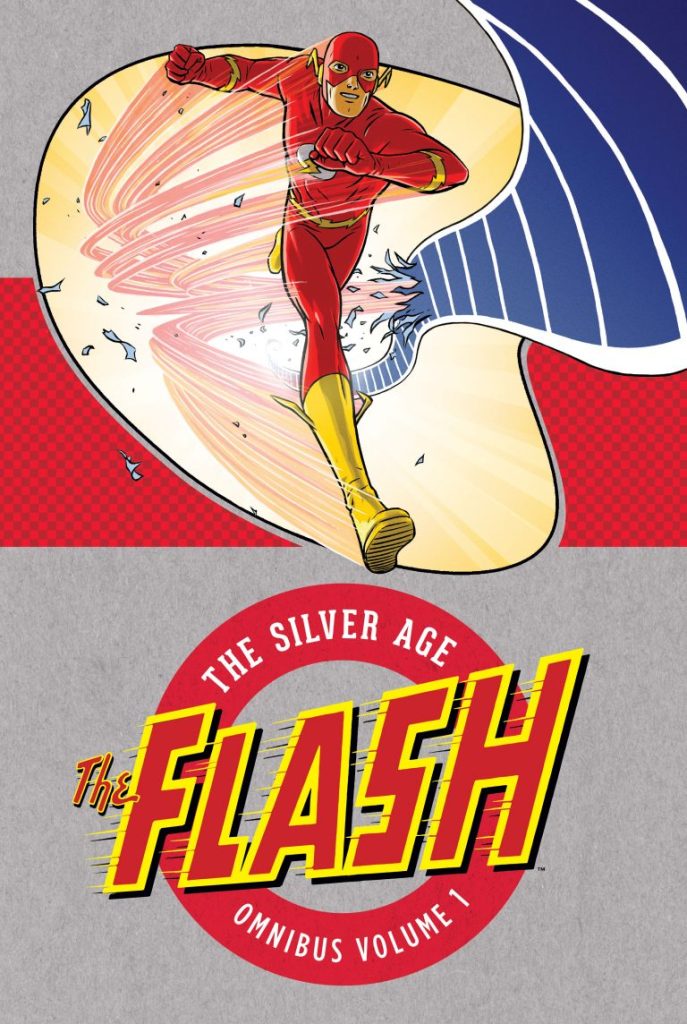

‘The Silver Age’ is the term used by superhero fans to denote the era when costumed heroes were revived, and although arguments can be made for other starting dates, the consensus is that it began with the Flash’s return in 1956. In truth, some superheroes never disappeared at all, and it had only been seven years previously that the final solo adventure of the original Flash was published, yet the arrival of Barry Allen was a landmark.

What made him so different was the art of Carmine Infantino. Ironically, Infantino had drawn the final adventures of Flash’s helmeted predecessor, but his art had undergone considerable change over the intervening period. No longer in thrall to the kinetic, heavily inked newspaper adventure style personified by Milton Caniff, Infantino took some faltering steps over the first half dozen Flash stories, published over an eighteen month period. However, once it became certain the revival was a success, Infantino had found his style. He would be able to take it further in later features, especially his work on Adam Strange, but Flash himself was just one part of a visual aesthetic. Equally important was his home of Central City, drawn by Infantino with reference to bold and sleek architectural design, and often seen as background solidifying Flash, so distinctive in his smooth red skintight suit in the foreground.

That costume has served for over seventy years and counting with only minor modifications, meaning there can be no argument about adjectives such as iconic and timeless being applied. Infantino also paid attention to women’s fashions, and there’s a consistent stylishness about Barry’s girlfriend Iris West. Barry himself, with his hat and checked jacket has fallen victim to time.

How Barry became able to move at super speed is a somewhat fudged origin from a period when a superhero’s deeds mattered more than their background. A chemical bath coinciding with a lightning strike was a once a lifetime event, except that three years afterwards it also happened to Iris’ nephew, enabling him to become Kid Flash in a story also included here.

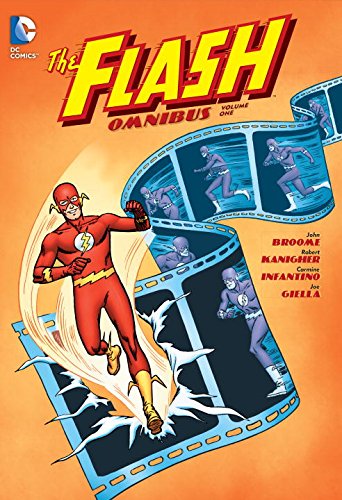

Robert Kanigher was responsible for the origin story, but John Broome defined the series before Gardner Fox also came on board. All three, Fox especially, had written the 1940s adventures of Barry’s predecessor, and presumably for the sake of nostalgia, his final outing by Broome and Infantino from 1949 opens this collection. As far as his replacement was concerned, the initial approach was to involve Flash in stories requiring scientific knowledge to provide solutions to mysteries, educating readers as well as entertaining them, but Broome also uses recurring colourful villains. Most who’ve plagued Flash over the decades are introduced in this content.

While the art can be admired, there’s no pretending these stories aren’t of their era. Plot vastly trumps personality and although the plots are clever, modern readers expect more.

The 2014 edition of this publication was just titled The Flash Omnibus, but this material has been issued in several other formats over the years. In colour it can be found in smaller hardcovers as four volumes of The Flash Archives, and in paperback as The Flash Chronicles, yet both series stalled before delivering the entire Broome, Fox and Infantino run. Subsequent to this Omnibus, four volumes of The Flash: The Silver Age have managed that, the first two splitting this content. So did Showcase Presents The Flash, but in black and white, and now increasingly hard to locate at a reasonable price. This, though, in oversized hardcover is the gold standard, with more to come in Volume 2.