Review by Ian Keogh

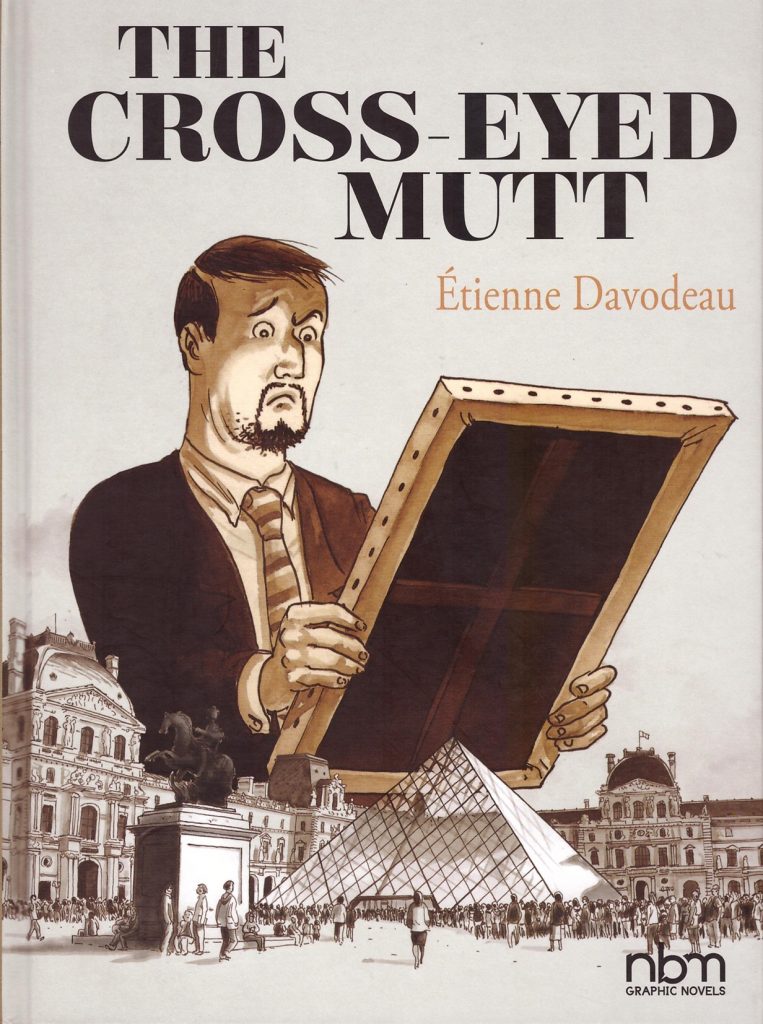

Based on the title, without reading The Cross-Eyed Mutt it may take some leap of faith to believe it as a work of wit, charm and elegance that questions the place of art. Yet it is.

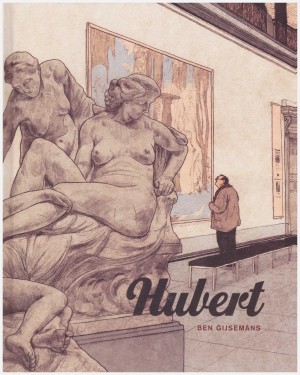

Fabien isn’t a man of great ambition, content to remain as a security guard at France’s most prestigious museum for fifteen years. He’s been seeing Mathilde for a while, and the time has come for him to meet her family, pre-warned that they’re a parade of eccentrics. What’s inevitably going to be a nervy situation anyway drops into excruciating when he’s shown a painting of a cross-eyed dog painted by an ancestor of the oldest Benion family member. Is it good enough to hang in the Louvre? It really would make their grandfather very happy.

This extremely awkward situation is Étienne Davodeau’s way into a discussion of how art resonates via the accepted masterpieces within the Louvre. What attracts people to certain pieces and not others? Who designates what’s worthy and what isn’t? This is amid some very funny anecdotal sketches around Fabien’s working day, a large list of thanks to Louvre staff after the story indicating Davodeau has sourced the ridiculous situations the staff encounter between constantly being asked where to find the Mona Lisa. It’s all cemented by the loving relationship between Fabien and Mathilde, very much invested in each other despite the occasional disagreement. Davodeau’s mastery of defining people visually combined with a finely honed sense of pacing and comic timing results in a captivating cast who can express more with a look than by saying anything. Better still everyone is deliberately depicted by Davodeau as ordinary rather than glamorous, with Fabien beautifully presented as a man whose certainties are being challenged and who’s consistently puzzled.

Davodeau subtly pursues his themes more broadly. It’s a rare scene set in Paris that doesn’t feature some form of art, be it 18th century architecture or the statues and fountains of the Tuileries Gardens. Why is something in a park and not the Louvre? The question of what constitutes authenticity is also addressed, although in a personal sense via the development of an elderly gentleman known to the Louvre staff as a regular visitor with a great appreciation for the art. It’s also there within the rigidity of how the Benions other than Mathilde view their family furniture business.

In case anyone’s left wondering, Davodeau concludes with an essay explaining the process required for work to be accepted into the Louvre, and constructs a neat solution to the problem of the cross-eyed mutt painting that should satisfy everyone. The Cross-Eyed Mutt is an intelligent piece that raises questions, leaving a big one nicely hanging, has a point to make and is thoroughly entertaining. Don’t miss out.