Review by Frank Plowright

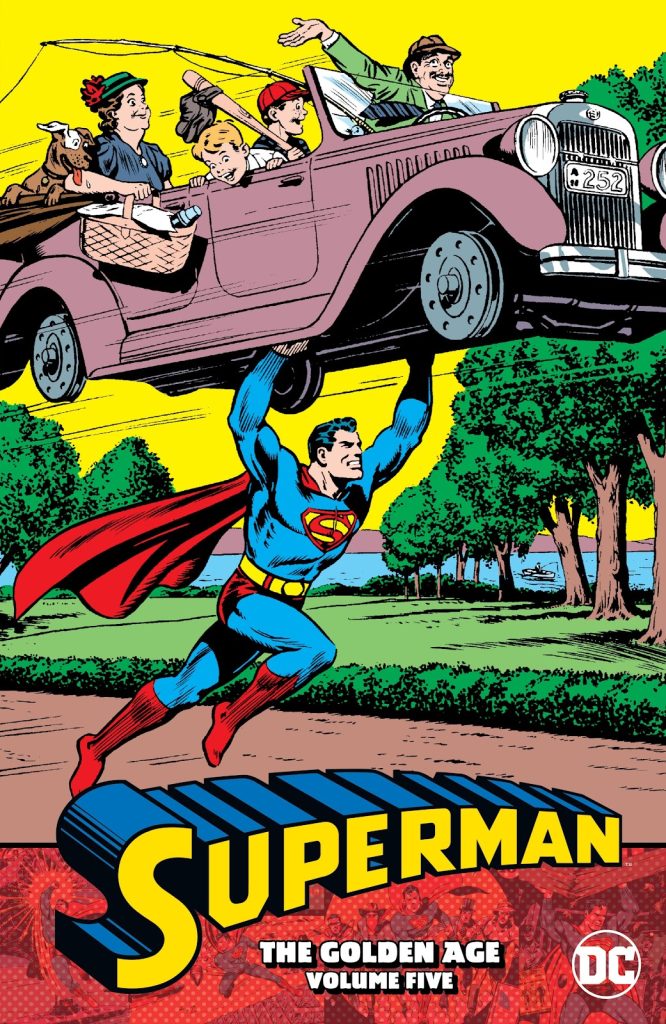

Jack Burnley’s strong cover composition brings the Americana of Norman Rockwell to mind, and also the question of why such covers are no longer considered viable beyond an occasional homage variant.

The contents continue the chronological reprints of the Superman’s appearances from Summer 1942 to early 1943, opening with an astute exploitation of social issues from Jerry Siegel. A crooked car dealer’s shoddy vehicles are responsible for a spate of crashes, and journalist Clark Kent is given the go-ahead to investigate. It’s followed by crooks stealing money raised for underprivileged kids, an astrologer with a surprisingly accurate prediction rate and gangsters running an extortion racket. For each set of crimes Siegel neatly constructs a human interest drama. After a while the formula of having to unmask the chief villain leads to predictability, so by midway through Siegel is planting red herrings.

In between tales rooted in reality, there are steps toward what Superman would become. He’s threatened by an other-dimensional villain, and matches wits with a crook named the Puzzler, who lives up to his name. The latter is the latest in a succession of humans adopting a sensational name, but Siegel works through his gimmick efficiently. By the end of this volume fantastic intrusions are becoming regular, with Superman now actually threatened. Siegel’s catch-all is that other dimensions are involved.

By now John Sikela is the artist of choice, drawing roughly two-thirds of what’s here. He has a busy action style for Superman in costume, characterises Clark and Lois well, and puts a lot of time into the splash pages and the larger illustrations now becoming a feature. In 1942 his cinematic breakdowns for Superman fighting the super strong Metalo included half-page illustrations and must have looked spectacular at the time. All but two stories not drawn by Sikela are the work of Leo Nowak.

Superman’s co-creator Joe Shuster only draws two stories, notably stiff when compared to Nowak and Sikela, but they’re landmarks. The second references the then new Superman animations, and in the first Siegel runs with the idea of Lois suspecting Clark is Superman based on his uncanny ability to place newspaper stories so rapidly. Forgetting the dead end obsessions the theme later spawned, it’s Superman neatly working his way around the problems. That same issue of Superman also introduces what would become the Fortress of Solitude, here just a secret citadel, but containing souvenirs and training devices. Another hint as to the future is the return of Lex Luthor, who escapes execution and develops super powers making him a match for Superman. Immediately afterwards the Prankster also returns, Sikela’s gap-toothed and staring version rather chilling.

Acknowledgement of the then ongoing World War II is largely restricted to the symbolism of Fred Ray’s comic covers, but Siegel does occasionally reference the wider world. A bizarre example is Superman readily agreeing to a faked Nazi invasion of Metropolis to wake up the citizens to danger, but it’s otherwise a plot with a clever twist. Elsewhere Siegel parodies the Li’l Abner strip, and gradually introduces comedy moments beyond Lois’ frustration at being beaten to the scoop by Clark again. Less welcome is her noticeably abducted more often.

Allow for the times, and this is another readable collection, and it combines what was previously issued in paperback as Superman Chronicles Volume Nine and Volume Ten. In hardcover the content appears in the third Golden Age Superman Omnibus, and spread over Action Comics Archives Volume 3 and Volume 4, and Superman Archives Volume 5.