Review by Frank Plowright

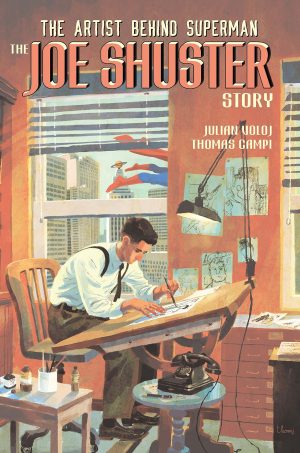

In the early 1930s two Cleveland teenagers took the conceptual leap of adding fabulous powers to the costumed adventurer seen in pulp magazines, and throwing in the exotica of having him come from another planet. Exploitation of that was still several years away when Superman headlined the first issue of Action Comics in 1938. It’s possible to quibble about finer details, but essentially Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created the superhero. Everything that’s followed from Batman to Spider-Man to Watchmen has built on what Siegel and Shuster developed, yet, incredibly in hindsight, it took them several years to persuade a publisher the concept was worthwhile. Publishers might have been blind, but the public knew a good idea when they read it, and two years after his introduction Superman was starring in three comics, a newspaper strip and a radio show, with cinema animation on the way.

For all that, Siegel and Shuster were essentially two enthusiastic amateurs learning on the job, and Siegel learned a lot faster than Shuster. Having Superman maintain the identity of journalist Clark Kent enabled Siegel to involve him in all kinds of stories prompted by the reporter’s employment, and Lois Lane’s presence added tension as readers worried that her plucky nature would lead her into trouble. Over this material she’s not yet developed into what people associated with her for so long. She has an acerbic tongue, but provokes all the right people for her journalism, and despite an attraction to Superman, she’s far from simpering. While there are some idle thoughts, setting elaborate traps to discover Superman’s civilian identity isn’t yet on her agenda.

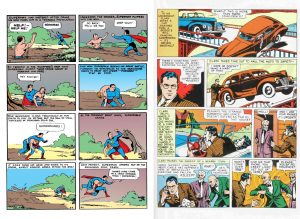

Shuster is a limited artist, even allowing for the comics of the late 1930s lacking illustrative sophistication, and his art doesn’t improve for being seen at a larger size. He’s at his best with Superman rushing about, but comparing his sample page with the art of Jack Burnley from 1940 shows a marked difference. Wayne Boring contributes some stories, but it’s the poorly credited Paul Cassidy responsible for several stories attributed to Shuster, the difference in layouts and the way the ‘S’ symbol is drawn on Superman’s chest proving identifying factors. Cassidy’s layouts are more interesting, and he’s better suited to conveying facial emotion.

It surprises how brutal the early Superman is, although always in the interests of helping people out, which is another surprise. He’s as likely to spend time stopping a share swindle or helping an orphan as he is dealing with an assortment of generic gangsters. Crooked businessmen also feature frequently in the earliest material, Siegel obviously having a strong sense of social justice, but these stories gradually diminish. Allowing for the occasional lapse along the way, the stories are increasingly deftly plotted morality dramas requiring Superman’s intervention, but with only two villains who’d recur. All four of the early, and very strange, appearances of the Ultra-Humanite are here, but he won’t be seen again until the 1980s. Lex Luthor proves more fitted for constant continuity, although in these earliest appearances he’s red-haired, the bald Luthor not appearing until Vol. 2.

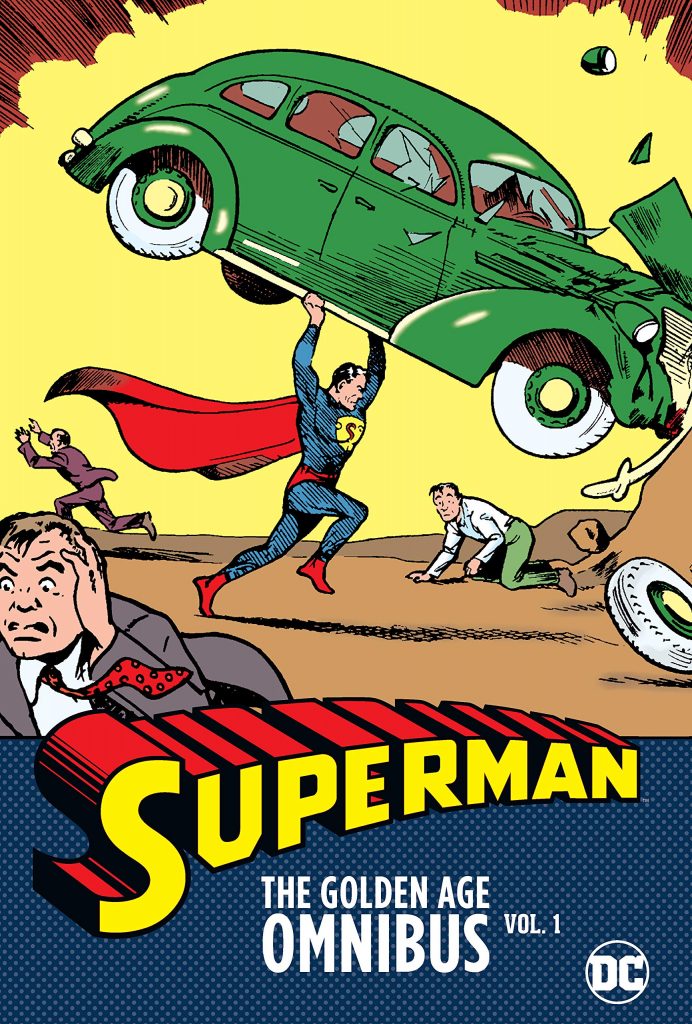

By contemporary standards, however much is owed to Siegel and Shuster, much of this early material is primitive. Don’t spend a fortune on this Omnibus without being prepared for that.

Alternative presentations are a combination of the first two Action Comics Archives and Superman Archives in hardback. In paperback they’re found in the first two volumes of Superman: The Golden Age, or the first four volumes of Superman Chronicles.