Review by Karl Verhoven

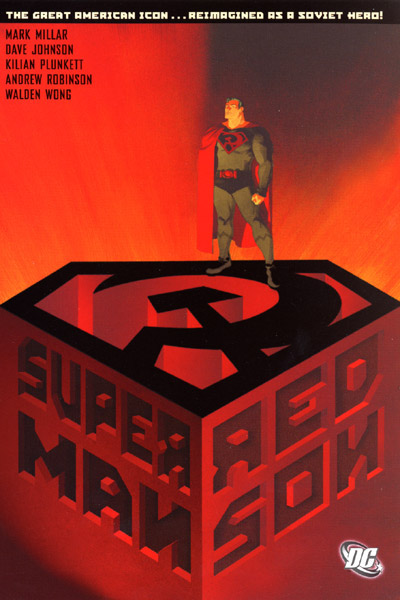

Mark Millar had always shown talent and promise, but Red Son was the project on which his widescreen scope began to gell. He delivered a high-concept plot seasoned with pithy dialogue in a convincing mileu, in this case the Cold War. Unfortunately that only applies to the first act of three.

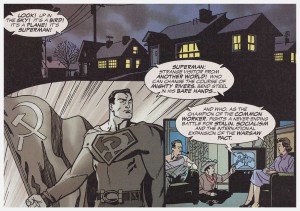

The foundation stone of Red Son is the smart twist of Superman’s rocket from Krypton landing not in Smallville, but among the fields of a Ukranian collective farm. By the time he’s announced to the world in the mid-1950s he’s accepted Soviet political ideology and immediately relegates the hydrogen bomb to obsolescence by virtue of his instant deployment capability.

Miller plays him sparingly at first, focussing on the rumours and fears of ordinary US citizens, before switching his attention to Superman’s unwilling involvement in Soviet politics and the anomaly of a Superman representing a system where all men are supposed to be equal.

As impressive as Millar’s recasting of Superman is, the fairy dust is also sprinkled on other familiar characters. We’re presented with a likeable Lex Luthor, a competent Jimmy Olsen and a sardonic and knowing Perry White, although Lois Lane is relegated to the role of wistful observer, wondering what might have been.

Where Millar is very good is by giving a knowing wink to the audience. “I honestly believe that Superman and I would have been the best of friends if he’d popped up in America” reveals Luthor at one point. “Either the Russians just landed in Idaho or J. Edgar likes to dress in ladies lingerie” offers White at the announcement of an impending big story.

A second act shifts the narrative to the 1970s and a third to the 1990s, but by this time Millar is resorting to familiarity as Superman encounters alternate versions of other DC characters and Luthor becomes less likeable.

Dave Johnson is an impressive cover artist, and produces imaginative panel compositions, but his interior work here is stiff and mannered, his best images involving elements of well-considered design. Around halfway through Kilian Plunkett takes over the pencilling, supplying more traditional layouts, but also more fluid action sequences.

Red Son is never poor, but the remainder doesn’t match the verve of the opening shot, although the final pages offer a deft conclusion. It’s a pointer as to what Millar would later refine and sustain.