Review by Frank Plowright

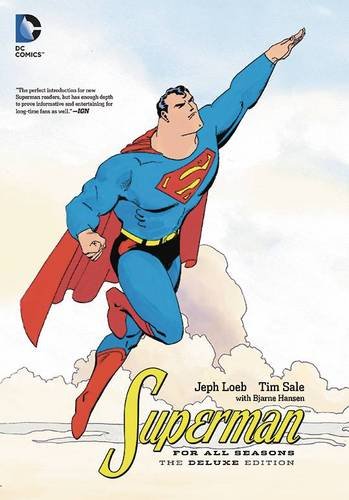

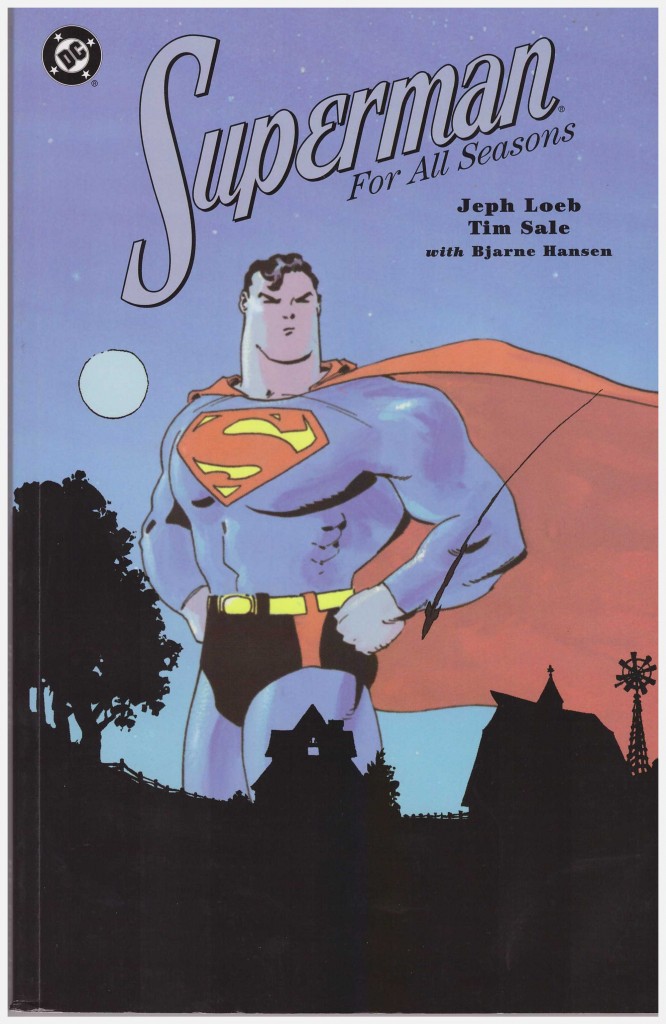

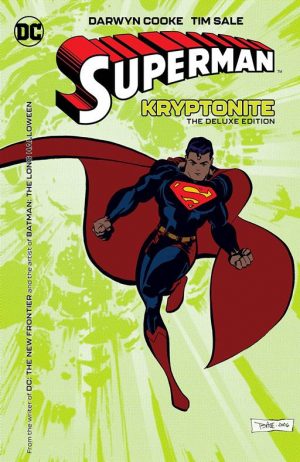

After their successful Batman miniseries Long Halloween and Dark Victory, the creative team of Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale turned their attention to Superman and delivered an entirely different style of story. They deliberately referenced their Batman projects by playing with opposites. Contrasting Batman’s enclosed dark world, Superman is presented in large expansive form, occupying space and basking in the light.

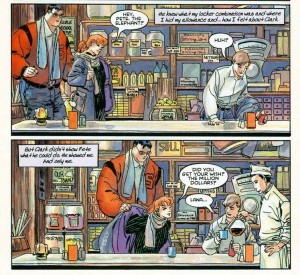

The story presents four narrative voices giving their impressions of Superman in an early stage of his career. In Smallville Jonathan Kent deals with a son having just realised the extent of his abilities and with that awareness comes the knowledge he has to leave. In Metropolis Lois Lane’s big city cynicism is swept away by a costumed man who can apparently do anything, yet chooses to be a hero. Lex Luthor’s view of Superman’s arrival in Metropolis isn’t as charitable. Supplanted as the most powerful and most interesting man in the city he falls back on being the richest to devise a threat, and Lana Lang’s whole view of the world is undermined on realising the future she planned wasn’t going to materialise. Splitting the book into seasons to accommodate the narrative quartet and title is a little forced, particularly as the metaphor only really works with spring and, at a stretch, fall.

The Superman portrayed here is genial and virtuous, and a circular element of Loeb’s plot permits him a chance to rectify a sin of omission made when uncertain. The country community of Smallville plays a large part, defining Superman’s idealistic worldview and remaining his anchor, his fortress of solitude as its referred to in a perhaps too knowing moment. Sale references Norman Rockwell and Loeb It’s A Wonderful Life, their touchstones for an uncomplicated era preceding their births.

Both keep it simple. Sale’s Superman is big-faced square-jawed lump of a man, and so is his Clark Kent, with the style an updated version of the character’s 1940s simplicity. He delivers big action moments, but they’re magnifications of an earlier era such as Superman stopping the speeding train. The retro approach earned Sale an Eisner Award in 1999. Loeb’s dialogue is restrained and very much weighed towards Smallville, but the one jarring note is his. A tragic super-character contrived to engender self-doubt is misplaced in an otherwise deliberately innocent package. The remainder more than compensates, and this remains among the ten essential Superman graphic novels.