Review by Frank Plowright

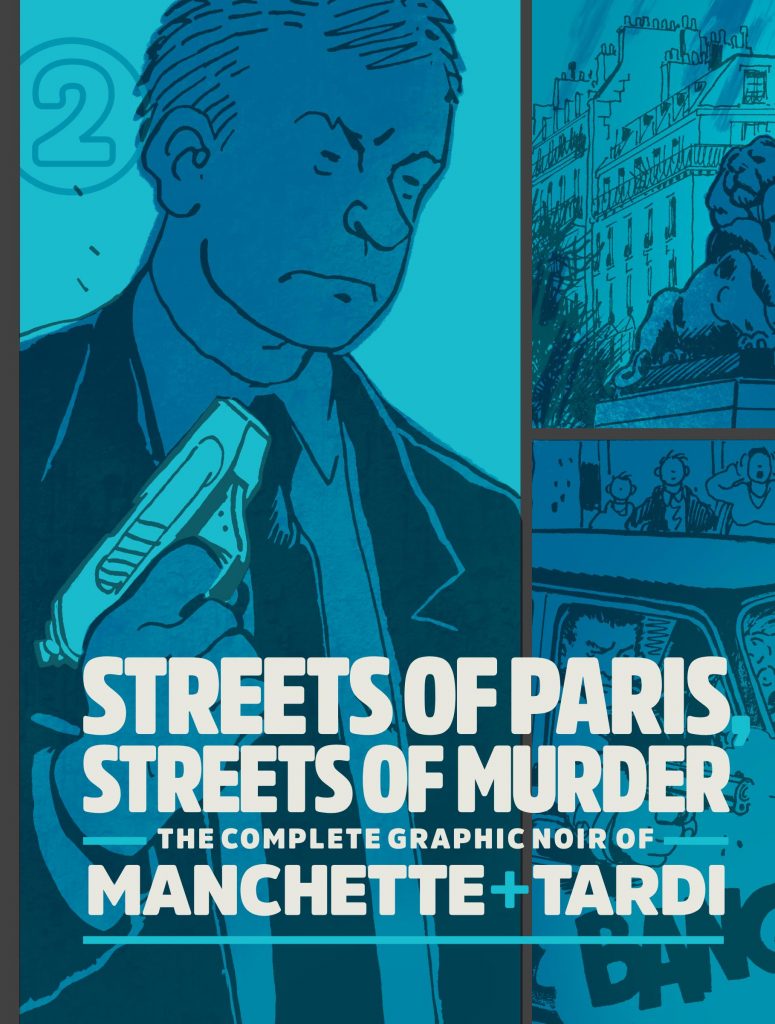

A second combined edition of Jacques Tardi adapting Jean-Patrick Manchette’s fevered crime novels pairs the 1981 Like A Sniper Lining Up His Shot with Run Like Crazy, Run Like Hell from 1972. Tardi adapted them respectively in 2010 and 2011. The short review is that both are psychologically observant and quirky dramas, certainly with a considerable element of criminal behaviour, but veering away from the traditional crime story via the defining characteristics assigned to the leading roles. Tardi’s art and sympathetic adaptations are first rate.

We’re first introduced to remorseless hitman Martin Terrier, single-mindedly driven by a promise made to him when he was sixteen. We see him going about his unpleasant business unflinchingly, lacking any concern for his victims, then handing in his notice in anticipation of the decade-old promise being kept. The complication is that he’s so good at his work, the people employing him are unwilling to lose such a valuable asset, and have means they believe will return him to their control.

The second story stars Julie, just released from a psychiatric clinic and immediately appointed nanny to the infant Peter, who’ll one day inherit the family business, run by his uncle until he comes of age. Julie doesn’t realise this unlikely scenario is setting her up to be the patsy in Peter’s ‘accidental’ demise, yet proves more than capable when it comes to ensuring his safety. She’s tracked by another of Manchette’s odd assassins, flawless killer and flawed individual Thompson, who’s constantly dosing himself due to experiencing nausea when tense.

Fatal infatuation and naive resourcefulness characterise two very different stories with contrasting moods. The first is slow and relentlessly bleak, Terrier understanding death, but not life, while the second is action-packed and optimistic, and a sometimes funny road story. Both throw curveballs and both are elevated by Tardi’s extraordinary art. Although written as contemporary thrillers, by the time they were adapted by Tardi over thirty years had passed, and he draws them as carefully constructed period pieces. The 1970s settings of both are meticulously apparent, most obviously in the use of old cars and trains, but also in smaller details. Tardi’s introduction to ‘Sniper’ points out an inclusion that could be missed in the reading, about how the newspapers read by Terrier refer to the 1979 death of French gangster Jacques Mesrine. Lush rural landscapes and distressed old buildings are as formidably drawn as the traffic and apartment blocks of the cities, while his people are permanently scowling and squinting.

Individually both stories were phenomenal when previously released, but combining them shows a versatility to Manchette’s approach, while more pages of Tardi’s art in one place can only be good.